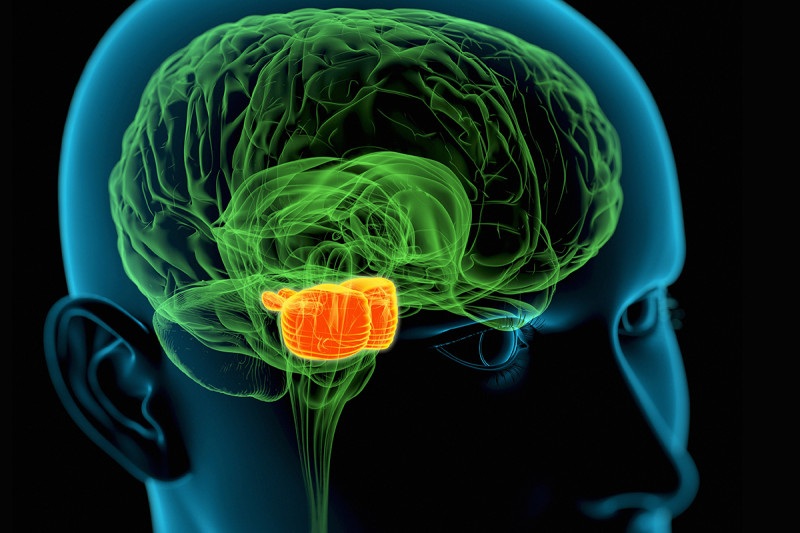

DIPG tumors begin in the middle region (orange) of the brain stem, which regulates many critical body functions. A new study suggests that a method for delivering drugs to these pediatric tumors could be safe and effective.

Brain tumors are notoriously hard to treat with drugs. Treatments such as chemotherapy have trouble getting through the aptly named blood-brain barrier. This membrane is very selective about allowing substances to pass from the bloodstream into the brain. Most drugs given by IV never make it to tumors in high enough concentrations to be effective. As a result, progress in treating some tumors has been agonizingly slow or even nonexistent.

Results from a phase I clinical trial led by researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering and Weill Cornell Medicine now suggest that treatment of some of the most difficult brain tumors may have taken a major step forward. The study tested a new drug delivery technique called convection enhanced delivery (CED). The findings indicate that CED appears safe and effective at distributing a drug throughout a fatal pediatric brain tumor called diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG). The encouraging results are published in the journal The Lancet Oncology.

DIPG tumors begin in the brain stem. This area at the base of the brain regulates many critical body functions, such as breathing, heart rate, and swallowing. DIPG is very difficult to treat because of its location and because the tumor cells can infiltrate normal brain tissue. Surgery is out of the question. The only traditional option has been radiation treatment, which has a minimal effect. Children with DIPG tend to live just a year or less.

The new study provides hope that drugs can be delivered more efficiently to DIPG tumors — and possibly other tumors located deep in the brain.

“This is somewhat groundbreaking because no one has taken CED into the brain stem with any type of systematic clinical trial,” says Mark Souweidane, a pediatric neurosurgeon at MSK and Weill Cornell who led the study. “All we had before were a few anecdotal cases. This trial shows we can use this very powerful drug-delivery platform repeatedly and safely.”

Slowly Pushing from Cell to Cell

The CED approach for DIPG involves slowly infusing the drug through tubes inserted deep into the brain stem. The delivery time lasts up to 12 hours. This extended flow allows the drug to gently push through the fluid compartment between cells in the tumor due to tiny differences in pressure. The drug saturates more of the tumor than has been possible through other delivery techniques.

So far, CED has been tested more on adult brain tumors, such as glioblastoma, another aggressive cancer. Dr. Souweidane thinks the drug delivery technique is better suited for DIPG because these tumors are smaller and restricted to a tighter area.

The research underpinning the use of CED for DIPG was an exhaustive effort conducted at Weill Cornell, where Dr. Souweidane is Director of Pediatric Neurological Surgery and Co-Director of the Children’s Brain Tumor Project. The clinical trial, which began in May 2012, took place at MSK.

In the trial, 28 children with DIPG who had already received radiation therapy to the tumor were given a drug called 124I-8H9 using CED. This drug consists of an antibody linked to a radioactive substance. The antibody binds to a protein on the surface of brain tumor cells, and the radiation emitted kills the cancerous cells. MSK physician-scientist Nai-Kong Cheung created 124I-8H9. The drug has already proven effective in treating metastatic neuroblastoma to the brain.

At seven different dose levels, the delivery method appeared safe in children with DIPG. Researchers determined that 124I-8H9 was well distributed through the tumors by tracking the radioactive substance using PET/CT scans and MRI. Most impressively, the investigators were able to prove that drug concentrations in the tumor were more than a thousandfold higher than anywhere else in the body — a remarkable improvement over what is typical. These results validated using CED for children with DIPG.

The trial did not examine whether this drug delivery approach caused the children to survive longer. It did establish that CED merits further development as a treatment for children with DIPG.

Remaining Challenges

Dr. Souweidane says that data gathered from this trial will guide the next steps toward refining the technique. How much of the drug made it into the tumor, how long it stayed there, the best ways to image and measure results, and other vital information will be assessed to come up with the best therapeutic strategy.

There are still many challenges to overcome. Researchers need to know how much of the tumor must be permeated for the drug to be effective. It also needs to be firmly established that children with DIPG truly benefit from this delivery approach. But proving the feasibility of the technique was a major hurdle.

“This has been revolutionary in my mind,” Dr. Souweidane says. “Our pharmacologists look at the results and say, ‘Where has this been for as long as we’ve been trying to treat these brain tumors?’”

A Long Journey

The success of the trial represents a milestone in a long journey for Dr. Souweidane. He has been studying DIPG and CED’s therapeutic potential for more than two decades. Preclinical work at Weill Cornell enabled Dr. Souweidane to test CED’s safety, efficacy, and proper dosage in rodents, using the findings to refine the technique. The lack of progress in treating the disease, especially compared with other childhood cancers, has taken a heavy emotional toll.

In 2016, Dr. Souweidane’s mission to cure DIPG was highlighted by photographer Brandon Stanton for the popular photo blog Humans of New York as part of a pediatric cancer series Mr. Stanton was shooting at MSK. The stories inspired a huge number of people to take action: Overnight, Dr. Souweidane’s laboratory received $1.2 million in donations to help him find a cure for the devastating disease.

These funds were not used for the clinical trial, which was already well under way. But they are now being applied to accelerate the next steps of the process to make it better.

Dr. Souweidane says this will involve a soon-to-be-opened trial through the Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium, a collaboration among 11 academic centers and children’s hospitals in the United States. The trial could begin as early as late 2018.

“This is the most exciting thing I’ve done in my career by far,” he says. “I’ve been in this for 30 years, and you just watch these kids die with no alternative. It’s constant, constant turmoil and tragedy. It’s amazing to think you’re on the verge of something big.”