The US Food and Drug Administration has approved the drug enasidenib (Idhifa®) for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) that has stopped responding to other therapies.

The FDA based its decision on the results of a phase I/II trial led by Memorial Sloan Kettering hematologist-oncologist Eytan Stein. People receiving the drug had higher response rates and lived significantly longer than is typical with existing treatments for the disease. Dr. Stein presented the study’s data in June at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. A paper detailing the findings was simultaneously published in the journal Blood.

Enasidenib is the first drug of its kind to be approved for any cancer. Rather than kill cancer cells, enasidenib rehabilitates them. It allows them to develop as normally functioning blood cells, reversing a stalled developmental state that causes the cells to behave as wayward miscreants. This makes the treatment much less toxic.

“Most of our drugs for AML are toxic to cells. Patients have this prolonged period of bone marrow suppression, which can lead to dangerous infections,” Dr. Stein notes. “This is a drug where you don’t see that. Instead, you see the differentiation of cells into normal, healthy adult cells.”

Enasidenib is an oral medication that people can take at home, with a low risk of side effects.

Birth of a New Drug

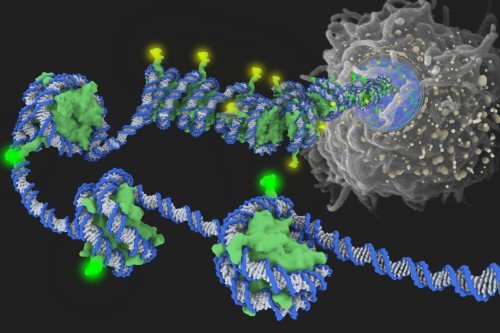

Enasidenib (previously known as AG-221) belongs to an emerging class of epigenetic drugs. These medications work to correct patterns of misdirected gene activity stemming from the way DNA is packaged in cells. Epigenetics has captured the attention of cancer biologists because, in principle, this altered DNA packaging is more easily fixed than changes in the DNA sequence itself. MSK’s Center for Epigenetics Research is a leader in this field.

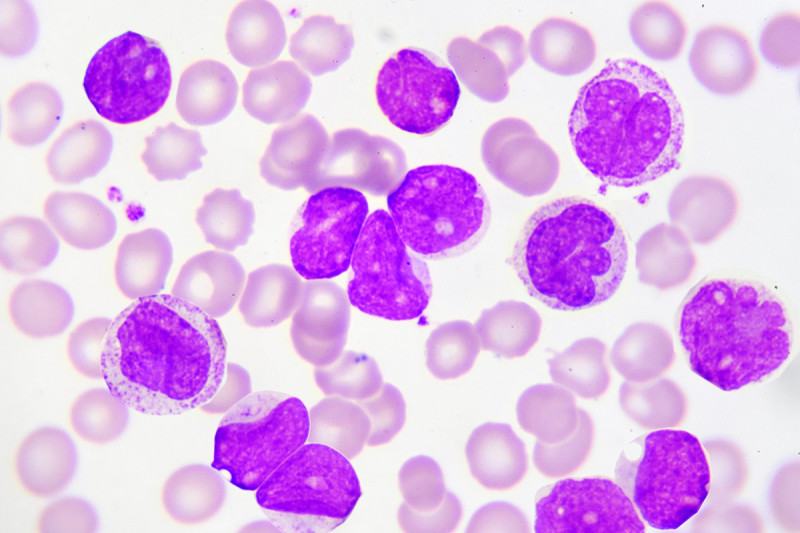

The scientific rationale for enasidenib in particular goes back to genetic evidence unearthed about seven years ago. By sequencing the genome of cancer cells in people with AML, scientists discovered that about 12% have a mutation in a gene called IDH2. The mutation causes the protein made by this gene to go haywire. Instead of doing its normal job, the protein produces a molecular byproduct called 2-HG. The troublesome offshoot interferes with a cell’s ability to remove methyl groups from its DNA. With too much methyl around, a cell’s transcriptional machinery can’t get to the DNA. The inability to access DNA prevents cellular differentiation, because the cells can’t turn on the genes they need to grow up.

“That’s sort of the definition of leukemia,” Dr. Stein points out. “It’s the accumulation of immature white blood cells.”

These discoveries led to the idea that if you could block the mutant protein, you could lower levels of 2-HG. That would restore a cell’s ability to remove superfluous methyl groups, and its ability to differentiate.

MSK’s President and CEO Craig Thompson did much of the preclinical work deciphering the relationship between the IDH2 mutation and the block to differentiation, including work done while he was a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. MSK physician-scientists Ross Levine and Omar Abdel-Wahab were key collaborators in this research.

Scientists at Agios Pharmaceuticals, the maker of enasidenib, undertook the development of a molecule that could specifically block the action of the mutated enzyme. “They did all the structural modeling and chemical research that developed the drug that fits into the binding site of the mutant enzyme,” Dr. Stein says.

On the clinical side, MSK played a lead role in testing the drug’s safety and efficacy. “We’ve accrued the most patients onto the trial,” Dr. Stein says. “We’ve been driving a lot of the clinical development and also the correlative science to understand what’s happening in patients.” Overseeing this clinical effort is Martin Tallman, Chief of the Leukemia Service.

Safe and Effective

The clinical trial of enasidenib, conducted between 2013 and 2016, enrolled a total of 239 people with myeloid malignancies that had an IDH2 mutation. Included were 176 people who had relapsed or refractory AML. Most of these individuals had received two or more prior therapies. The trial showed that the drug was safe and generally well tolerated. The most common side effects were jaundice (38%) and nausea (23%).

The overall response rate for those with AML was 40%, with a median overall survival time of 9.3 months and an estimated one-year survival rate of 39%. For the 34 people (19.3%) who attained a complete response, the median survival time was 19.7 months. This study did not directly compare enasidenib with standard-of-care chemotherapy, but historically people with relapsed or refractory AML have an average survival time of about three months. These extensions in survival time are therefore significant.

Moreover, people taking the drug start to feel better almost immediately because the level of their infection-fighting white blood cells rapidly returns to normal.

“It’s really a transformation,” Dr. Stein says. “Patients will go from being riddled with infections to having a normally functioning body. It’s pretty amazing.” (The dramatic experience of people taking enasidenib was the subject of a New Yorker article by Jerome Groopman in 2014 aptly called “The Transformation.”)

Unfortunately, most of the people who received enasidenib did eventually relapse. This points to the need to develop more-effective combinations of drugs. Clinical trials of several such combinations are ongoing. A few people in the study had very deep and long-lasting responses and are still alive and cancer free today.

Enasidenib is approved for people with relapsed or refractory AML that tests positive for an IDH2 mutation, as determined by an FDA-approved test.