There are many claims about the herbal remedy kratom, but none of these benefits have been demonstrated in rigorous clinical trials.

In the past few years, a number of companies in the United States have begun selling an herbal product called kratom, mostly online. The product, sold as dried leaves or a powder in capsules, comes from a tropical tree that grows in Southeast Asia.

Proponents of kratom say that it acts as a painkiller and a sedative, among other effects. Some people believe it can treat opioid or alcohol addiction. But none of these benefits have been demonstrated in rigorous clinical trials.

Negative events associated with consuming products that contain kratom have been reported. Many of these cases were caused by long-term abuse. In addition, kratom products have been connected to recent outbreaks of salmonella that sickened about 200 people in several states.

Memorial Sloan Kettering neurologist and pharmacologist Gavril Pasternak is studying the active components of kratom to figure out what the herb does in the body. He’s collaborating on this work with medicinal chemist Susruta Majumdar, who was an assistant attending chemist at MSK and is now an associate professor at the Center for Clinical Pharmacology at the St. Louis College of Pharmacy and the Washington University School of Medicine.

Scientists believe that some of the ingredients naturally found in kratom may hold promise for developing new and better painkillers. These drugs could potentially have fewer side effects than those currently on the market.

How can a natural product become a medicine?

It’s not a crazy notion to think that a new drug could come from a tree. In fact, about half of all drugs sold today originated in living things, including plants, fungi, and bacteria found in the soil. These natural products include the heart drug digoxin, which is isolated from a flower called foxglove; the antibiotic penicillin, which comes from mold; and painkillers like morphine, which is made from poppies. Many cancer drugs are made from natural products too.

Natural products that are developed and sold as drugs may come directly from their source. They may also be created in the lab using chemical synthesis. Chemicals taken from living things may become the starting materials for making similar compounds. Chemists may alter naturally occurring molecules to come up with drugs that are more effective or have fewer side effects.

Can kratom block pain with less risk?

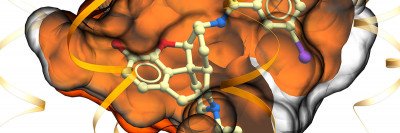

Like most herbal products that come from plants, kratom contains a mixture of many different chemical compounds. In 2016, Dr. Majumdar published a study in collaboration with Columbia University researcher Dalibor Sames showing that among the natural products found in kratom, two compounds activate opioid receptors in human cells — the same receptors activated by drugs like morphine and oxycodone, which are clinically used in the treatment of pain.

Later in the year, in collaboration with Jay McLaughlin of the University of Florida and MSK researchers Ying Xian Pan and Dr. Pasternak, Dr. Majumdar published another study, which reported that two compounds in kratom were more effective than morphine at blocking pain in mice. Their effectiveness was tested using what is called a tail-flick assay. In this assessment, a mouse’s tail is put next to something hot. The efficacy of the pain medication is determined by how many seconds it takes for the mouse to feel pain and flick away its tail.

Further investigations done in cells and mice determined how these molecules provided pain-blocking effects. “We found that these compounds are structurally different from drugs like morphine or fentanyl,” Dr. Majumdar says. “They bind to pain receptors in a different way.” Specifically, they act on the pathways that allow pain to be suppressed without acting on the pathways that suppress breathing. The addictive potential of the natural products found in kratom is presently being investigated and will soon be reported.

“This is a crucial safety issue since respiratory depression is responsible for overdose deaths from opioids,” adds Dr. Pasternak. He and Dr. Majumdar are continuing to work together to design novel drugs based on components in kratom that will be even more effective and safe.

The US Food and Drug Administration and US Drug Enforcement Administration are considering banning kratom. Scientists who study kratom say that such an action would effectively end their research because it would become exceedingly difficult to obtain and work with the compounds. Potentially promising leads for new drugs could be lost.

Can people with cancer take kratom now?

The type of kratom-derived drugs being developed by Drs. Pasternak and Majumdar are at least several years from being evaluated in clinical trials. But the experts in MSK’s Integrative Medicine Service who manage the About Herbs database frequently receive questions from people with cancer — as well as their doctors — about whether kratom as it is now sold is a safe and effective way to manage cancer pain. The database provides information about herbs and other complementary therapies that is based on scientific literature.

“A lot of people are interested in taking kratom for their cancer pain because they’re concerned about the addiction potential of traditional opioid drugs,” says pharmacist K. Simon Yeung, who manages About Herbs. “But right now, we don’t have enough information to know whether it is safe and effective for this purpose.”

“One problem with kratom is that it is a mixture of many different compounds whose levels can vary from preparation to preparation, making it quite difficult to determine what dose should be used,” Dr. Pasternak says. “People with cancer receive more effective and reliable pain relief with established painkillers.”

Dr. Yeung notes that concern about salmonella contamination makes it even more important to avoid kratom products. “One FDA analysis found that half of all kratom products evaluated were contaminated,” he says. “Because chemotherapy and other cancer treatments can weaken a person’s immune system, getting one of these infections could be very serious.”

MSK doctors stress that people with cancer should not take any herbal substances without first discussing it with their healthcare team.