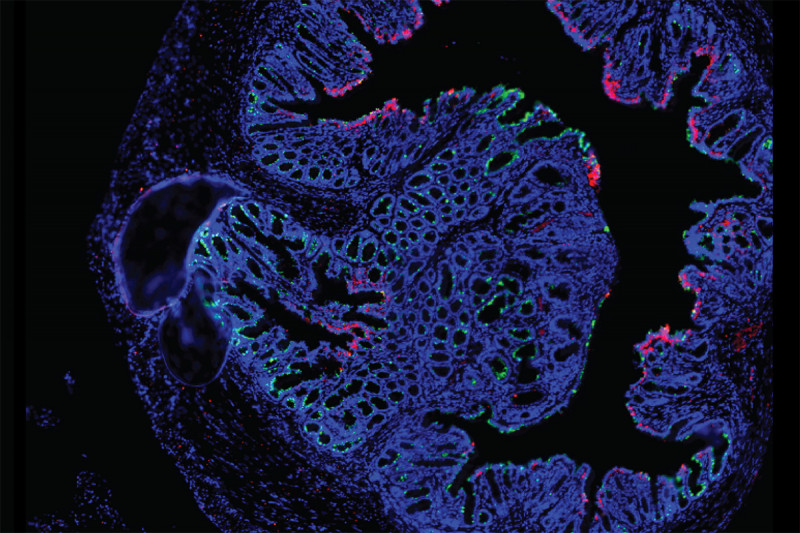

A portion of a rectal cancer organoid viewed with fluorescence microscopy.

Rectal cancer has been hard to study because, historically, there have been no reliable models of the disease. To address this deficiency, physician-scientists at Memorial Sloan Kettering set out to devise one, using human tumor samples as their starting point.

“There were really no great rectal cancer models, so we decided to tackle that problem,” says J. Joshua Smith, a rectal cancer surgeon and scientist in the Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program at MSK who led the multidisciplinary effort, which tapped the expertise of multiple MSK colleagues including Karuna Ganesh, Chao Wu, Julio Garcia-Aguilar, and Charles Sawyers.

The approach Dr. Smith and his colleagues took was to create something called a tumor organoid. This is essentially a miniaturized version of a rectal tumor that behaves like the real thing.

Scientists have previously created organoid models of colon cancer, but rectal cancer differs from colon cancer in important ways biologically.

As a surgeon, Dr. Smith was in a good position to take on the project. He and the MSK rectal cancer team care for more than 350 people with the disease per year. When performing surgeries or biopsies on his patients, Dr. Smith removed a little bit of tumor tissue. From the samples, the researchers were able to establish 65 rectal cancer organoids from 41 patients. This is the first time that scientists have developed a model of rectal cancer that reproduces all the characteristic features of the disease in a mouse.

“These organoids form invasive tumors in the mouse rectum just like those formed in humans,” Dr. Smith says. “We can see the whole progression, from adenoma to adenocarcinoma, and from adenocarcinoma to metastasis.”

The team reported their results in the journal Nature Medicine on October 7.

Modeling Drug Responses

The organoids retain the molecular and cellular features of the tumors from which they were derived. Because of that quality, the organoids may be able to help doctors predict how patients will respond to particular treatments.

When the investigators treated the organoids with chemotherapy or radiation, for example, the organoids responded the same way that the patients’ tumors did. Organoids from patients whose tumors responded to chemo or radiation displayed this sensitivity. Those from patients whose tumors did not respond were similarly insensitive.

If these findings hold for larger numbers of people, testing treatments on organoids could one day spare people from chemotherapy or radiation treatments that would have no benefit.

Even more tantalizing, many of the organoids spread to the same organs as the original tumors. “Clearly, more work needs to be done to confirm this finding,” Dr. Smith says. “But if these findings persist, they will inform our understanding of the underlying biology of how rectal cancer spreads and how and why some tumors are resistant to therapy.”

Creating a Portal for Researchers

Dr. Smith and his colleagues plan to make the organoids available to researchers from other institutions. He is actively working with Nikolaus Schultz, Francisco Sanchez-Vega, and Michael Berger of the Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology at MSK to establish an online portal for the organoids. Researchers will be able to see specific details about the patients and tumors from which the organoids were derived and order a certain one.

“My goal is to create the world’s largest biorepository of rectal cancer tools and to make these available to researchers who want to move the needle to better patient care,” he says.