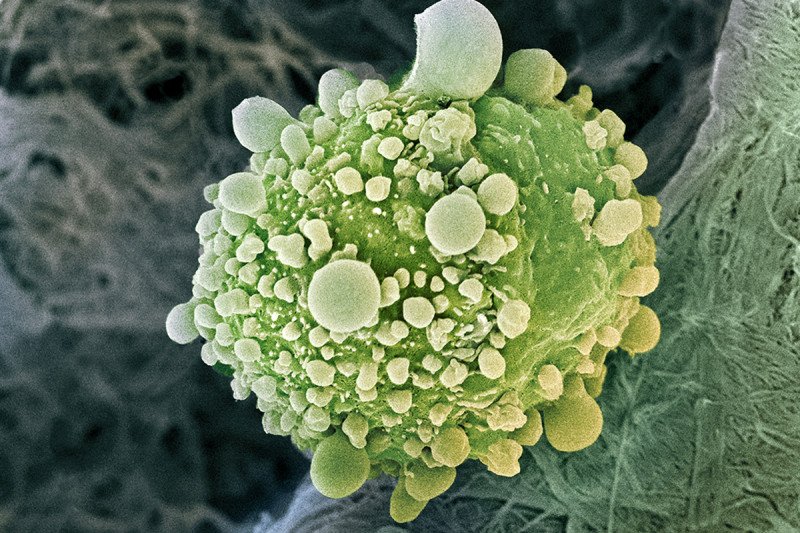

Cancer is the result of mutations that accumulate in cells over time. These genetic changes cause cells to multiply at an uncontrollable rate. In some cases, they break off from the tumor and establish themselves in another part of the body — a particularly deadly aspect of cancer known as metastasis.

In pancreatic cancer, researchers have had a difficult time developing new therapies for metastatic disease. This is in part because the tumors are particularly heterogeneous — cells within the same tumor in the same patient can appear vastly different from each other. Because of that, researchers have long assumed that there were many different driver mutations in play that induced tumor formation and growth.

Now, for the first time, an in-depth study of four patients who died of metastatic pancreatic cancer has shown that the same mutations are involved in driving the primary tumor and the metastases. The findings offer insight for using targeted therapies in advanced pancreatic cancer because they suggest the same treatment may work on both the primary tumor and the metastases.

“In this study, we took advantage of a unique resource — tumor sequencing data on patients who died of pancreatic cancer before they ever received treatment,” says Memorial Sloan Kettering physician-scientist Christine Iacobuzio-Donahue, Associate Director for Translational Research in MSK’s David M. Rubenstein Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research. Dr. Iacobuzio-Donahue was one of the senior authors of two related studies being published this week in the journal Nature Genetics in collaboration with researchers at Johns Hopkins University and other institutions.

“Treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation can change the genetics and behavior of tumors, so this allowed us to study the natural history of the disease and how it spreads,” she adds. “What we found was unexpected.”

Finding Mutations that Drive Cancer

The researchers discovered that each patient had his or her own unique set of driver mutations that were shared among all the tumors, both primary and metastatic. “This means that for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer, we could perform a single biopsy of just one tumor, and by analyzing that tumor, potentially identify a treatment that would be effective against all of them,” Dr. Iacobuzio-Donahue explains.

At MSK, all patients with metastatic cancer have their tumors analyzed using a technology called MSK-IMPACT, which looks for more than 400 genetic alterations known to play a role in cancer. By identifying these mutations, clinicians are able to determine which treatments are most likely to be effective — whether those are standard therapies or ones offered through clinical trials. Some patients may qualify for basket trials, in which they receive therapies based on the mutations in their tumor rather than on where in their body the tumor originated.

Looking at Changes Beyond the Genes

In a second, related study, researchers found that although driver mutations were the same in both the primary and metastatic tumors, the metastatic tumors did have additional changes that could be targeted with a second type of treatment.

These changes were what are known as epigenetic changes, which affect the way that genes are expressed without changing their sequence. In particular, the epigenetic changes in many of the metastatic tumors studied were related to cell metabolism.

“Once we identified these epigenetic changes, we were able to find a molecule that could reverse the alterations in metabolism,” Dr. Iacobuzio-Donahue says. “In mouse models, we showed that this molecule was able to reprogram the metastatic cells and reverse their ability to colonize other parts of the body and form tumors. We hope to eventually look at it in clinical trials.”

Distinctive Program Enables Patients to Contribute to Research

The patients’ tumors were available for research thanks to MSK’s Medical Donation Program, which Dr. Iacobuzio-Donahue leads. The program allows people to donate their body to MSK after they die, enabling researchers to analyze tumors that they otherwise would not be able to access safely during life.

Dr. Iacobuzio-Donahue says the program can provide great comfort to patients who are dying of cancer, knowing that they will be able to play a role in improving the understanding of the disease. “It gives them the sense of leaving a legacy and contributing to something bigger than themselves,” she explains.