A Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) research team has identified a new, rare type of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) — dubbed “atypical SCLC” — that primarily affects younger people who have never smoked.

Their findings, published recently in Cancer Discovery, included a detailed analysis of the clinical and genetic features of the disease and highlighted vulnerabilities that may inform better treatment decisions for affected patients. (1)

“It’s not every day you identify a new subtype of cancer,” said first author Natasha Rekhtman, MD, PhD, an MSK diagnostic pathologist with expertise in thoracic pathology and cytopathology. “This new disease type has distinct clinical and pathological features and a distinct molecular mechanism.”

The study brought together the expertise of 42 physicians and researchers across MSK — including pathologists, thoracic medical oncologists, and specialists in tumor genetics and computational analysis.

“Understanding this new type of lung cancer required a broad spectrum of expertise from the laboratory to the clinic,” says Charles Rudin, MD, PhD, a lung cancer specialist and the study’s senior author.

Defining a New Lung Cancer Subtype: Atypical Small Cell Carcinoma

SCLC is relatively rare, accounting for only 10% to 15% of lung cancers. The newly discovered lung cancer subtype was found in small fraction of SCLC cases: Out of 600 patients with SCLC whose cancers were analyzed, only 20 or 3% were found to have atypical SCLC. (1)

“Patients who develop typical SCLC tend to be older with a significant history of smoking,” says Dr. Rudin, the Cancer Center Deputy Director, Co-Director of the Fiona and Stanley Druckenmiller Center for Lung Cancer Research, and Sylvia Hassenfeld Chair in Lung Cancer Research at MSK. “The first patient we identified with atypical SCLC was just 19 years old and a nonsmoker. That case led us to look for more.”

The mean age at diagnosis for patients with atypical SCLC was 53, much younger than the average age of 70 for lung cancer in general. Sixty-five percent of the patients with atypical SCLC were never smokers, while 35% reported a history of light smoking (less than 10 pack-years). (1)

Atypical SCLC appeared to arise through a transformation of lower-grade neuroendocrine tumors (pulmonary carcinoids) into more aggressive carcinomas. While SCLC is normally characterized by the deactivation of RB1 and TP53 genes, the MSK researchers found that patients with the new subtype had intact copies of those genes. Instead, most carried a signature “shattering” of one or more of the chromosomes in their cancer cells, an event known as chromothripsis. Specifically, the chromothripsis recurrently involved chromosomes 11 or 12, resulting in extrachromosomal amplification of CCND1 or co-amplification of CCND2/CDK4/MDM2. (1)

Treating Atypical Small Cell Lung Carcinoma

The researchers found that atypical SCLC tended to be somewhat less aggressive and affected individuals who were considerably younger and healthier than most people diagnosed with SCLC.

Their analysis also found that standard, first-line, platinum-based chemotherapies for treating SCLC did not work as well in addressing the unique genomic changes that give rise to atypical SCLC. (1)

“We often talk about cancer as an ongoing buildup of mutations,” Dr. Rekhtman says. “But this cancer has a very different origin story. With chromothripsis, one major catastrophic event creates a Frankenstein out of the chromosome, rearranging things in a way that creates multiple gene aberrations, including amplifying certain cancer genes.”

The MSK research team’s findings revealed that patients with atypical SCLC may benefit, for example, from investigational drugs that target the unusual DNA structures resulting from chromothripsis, known as extrachromosomal circular DNA. (1)

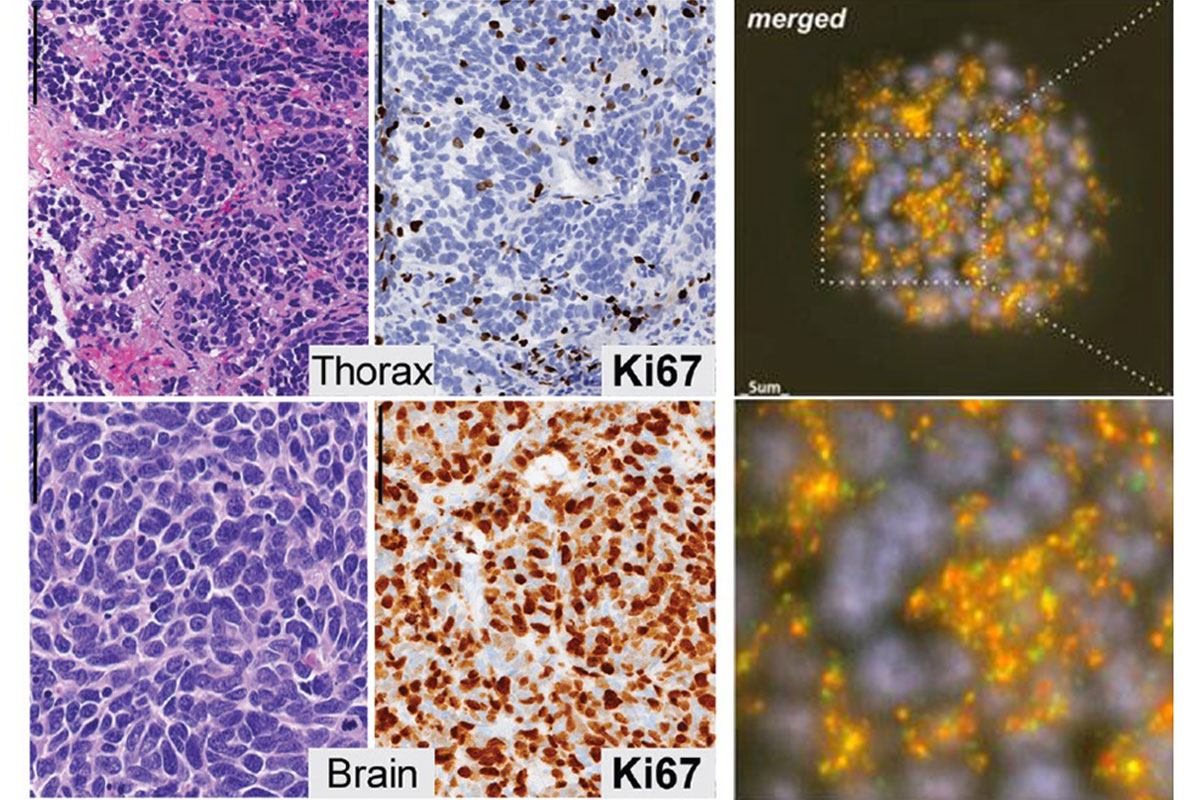

On the left, four pathology images from a patient with atypical SCLC show hallmarks of carcinoid cancer in the lungs (thorax), but signs of classical small cell lung cancer where it has spread to the patient’s brain. Ki67 is a marker of proliferating cells, which are an indication of cancer. On the right, the bottom image shows a zoomed-in section of the top image. Here, researchers used an imaging technique called FISH to examine extrachromosomal amplifications (the colorful structures) associated with chromothripsis — chromosomal shattering — in this rare cancer. Images via Cancer Discovery (CC BY 4.0).

The MSK Research Advantage

MSK patients routinely have their tumors sequenced with MSK-IMPACT®, which analyzes changes to more than 500 genes known to drive cancer and helps oncologists identify drugs that will work best against specific mutations.

“So not only were we looking at patients with specific demographic characteristics — young never-smokers — we were able to take advantage of this unique MSK resource to look for patients whose tumors shared the same genomic features,” Dr. Rekhtman says.

Moreover, the wealth of sequencing and treatment data available at MSK allowed researchers to compare treatment programs and outcomes from the patients they identified with the new subtype, which helped them zero in on strategies that may help other patients diagnosed with atypical SCLC.

“There were some major lessons we learned from these patients,” Dr. Rudin says. “In general, they don’t respond as well to standard treatments as typical SCLC patients, but our study suggests several potential emerging or established therapeutic opportunities.”

“Overall, our work exemplified the deep interconnection between patient care and research at MSK,” Dr. Rudin says.

The study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R35 CA263816, U24 CA213274, P30 CA0087448), the Druckenmiller Center for Lung Cancer Research, and Sharon and Jon Corzine. Access disclosures for Dr. Rekhtman and Dr. Rudin. For the complete list of authors, please refer to the paper.