Despite the proven benefits of exercise, even while receiving treatments, new research from Memorial Sloan Kettering’s Integrative Medicine Service shows that the majority of cancer patients report significant decreases in their physical activity levels after their cancer diagnosis.

The results, which were reported at the recent ASCO Cancer Survivorship Symposium, showed that patients identified both psychological and physical barriers as factors in their decrease in activity.

As of January 2016, 15.5 million Americans were living with a cancer diagnosis. (1) Cancer patients experience many bothersome symptoms, including pain and fatigue, which can impact their ability to maintain physical activity (PA) levels post-diagnosis.(2),(3) We know that physical activity is important for cancer prevention; (4) however, emerging evidence demonstrates that physical activity not only may help patients to feel better but also may improve their cancer outcomes. (5)

Our Recent Research Findings: Barriers to PA

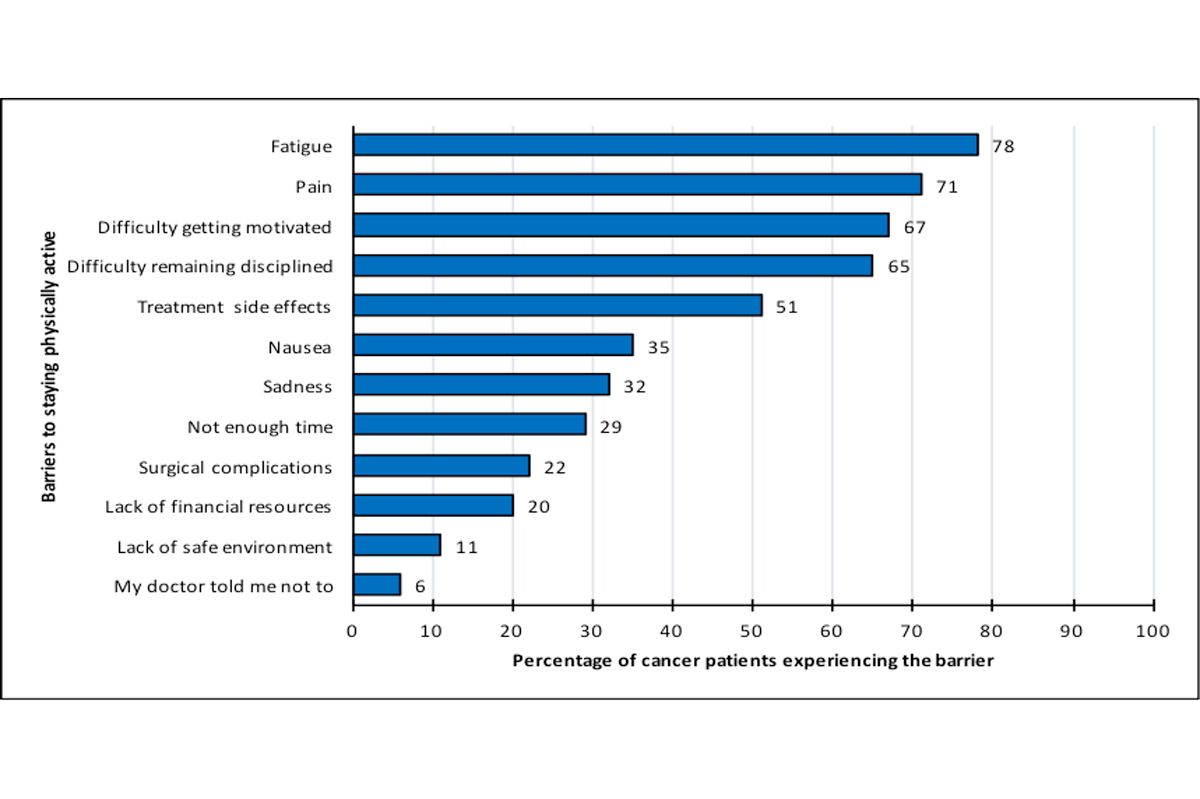

We recruited 662 cancer patients from one urban academic center and 11 affiliated community hospitals in the Philadelphia area to participate in a cross-sectional study and found 499 (75%) reported decreasing their PA levels, while only 16% maintained, and 4% increased their PA levels. We identified psychological barriers such as difficulty getting motivated (67% of subjects) and trouble remaining disciplined (65%), as well as physical barriers, including fatigue (78%) and pain (71%) associated with cancer treatments, as factors contributing to this decrease in activity.

Guidelines for Physical Activity in Cancer Survivors

The American Cancer Society (ACS), American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) have made physical activity recommendations for cancer survivors post-diagnosis, including for improvements in managing common side effects such as fatigue and pain. Among the basic agreed-upon recommendations are that all patients avoid inactivity and return to normal daily activities as soon as possible after diagnosis; that they engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate or 75 minutes of vigorous aerobic exercise per week; and that they include strength-training exercises at least two days per week.(2),(3) To improve flexibility, adults should stretch major muscle groups and tendons on days they participate in other types of activity; older adults will also benefit from balance exercises. (6)

Although most physical activity is safe and effective, exercise prescription and goals will vary depending on a patient’s diagnosis and side effects. Those survivors with multiple or uncontrolled comorbidities or who are at higher risk of injury, such as those living with neuropathy, cardiomyopathy, or other long-term effects of therapy, and patients with severe fatigue that interferes with physical function should be referred to a physical therapist or exercise specialist and consult with their physicians.(2),(5) Exercise may not be recommended for cancer patients with severe heart disease or physical pain and functional limitations. These patients should be evaluated by a cardiologist or by a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician before doing any intense workouts or activities. However, in general, many survivors may safely begin a low- to moderate-intensity exercise program, such as walking, without being supervised or evaluated by an exercise specialist. (6)

MSK’s Integrative Medicine Service

Many cancer patients have late effects that may inhibit their quality of life. Integrative medicine therapies such as acupuncture, massage, and yoga can, in many cases, help manage the physical and emotional symptoms, including pain and fatigue, that people commonly experience during and after cancer treatments.(7)-(9) For those patients who are struggling with limitations, our Integrative Medicine Service fitness specialist, who is also an experienced cancer nurse, provides a wide range of group exercise classes and personal training sessions to support people undergoing treatment for cancer, regardless of their condition or the stage of their illness. She commonly receives referrals from rehabilitation nurses as patients complete their rehab program and are in need of total-body fitness, including mobilization stretches, cardio fitness, resistance training, and core exercises and stretching. She also receives calls from patients who have been prompted by their doctor or nurse practitioner (NP) to inquire about exercise services. In order to reach patients who may not be notified about our services through either of the above referral methods, our expert goes directly to MSK waiting areas, asks patients if they have any questions about exercise, and provides them with information on available services.

Reaching out to MSK patients through either provider referrals or in waiting areas has encouraged a number of patients to engage in physical activity and led to remarkable improvements in their quality of life and cancer outcomes. For example, we treated a 65-year-old woman who was diagnosed with lung cancer and underwent a pneumonectomy. Post-surgery, she experienced immense pain, anxiety, shortness of breath, and other symptoms, resulting in her need for daily pain, anxiety, and other medications. She also struggled to resume her normal life activities, including work, family obligations, and an exercise routine of jogging and weight lifting. Four months post-surgery, a thoracic oncology NP referred her to our exercise specialist to assist with breathing and an exercise program. Our specialist met with her twice a week and designed a home program for her. As she started to slowly incorporate exercise back into her weekly routine, she was able to start reducing her pain and other medications. Today, as a six-year cancer survivor, she is able to jog two miles and no longer needs any pain medications.

Get Moving: Practical Tips

As our study demonstrates, becoming physically active can be challenging during and beyond cancer treatment. We should not only ask patients whether they are participating in physical activities, but also help them to identify the barriers they experience and develop solutions to remove these barriers so that they become active. Patients who are ready to include physical activity in their treatment plan can start small with less-intense exercise in which they can gain confidence in their movements and reconnect with their bodies, slowly building strength, balance, and flexibility. An exercise prescription for adults at the time of cancer diagnosis can include a simple home program of 10 to 20 minutes of daily walking, arm circles for flexibility, and chair squats for lower-body strengthening. In a class setting, participants can begin by sitting in chairs and doing breathing exercises and warm-up static and mobilization stretches, followed by 10 to 15 minutes of walking aerobics using music and movement patterns. Participants can then return to their chairs for major muscle strengthening. It is important to keep the intensity low to moderate and continuously monitor that each participant is exercising in a safe manner. Over time, patients can increase their level of activity to include more intense exercise.

Next Steps

Further research is needed to better understand how clinicians and patients can work together to overcome the physical and psychological barriers to maintaining physical activity levels during the cancer-care continuum. In addition, interventions need to be developed that target self-reported barriers to exercise so that patients can manage their cancer-related symptoms, stay motivated, and maintain their levels of physical activity during and after cancer treatment.