Let's get started

World-class experts. Close to you.

Many treatments and services are available at locations across NY and NJ.

Get care from the comfort of your home with telemedicine from MSK.

Explore MSK’s clinical trials

Our doctors and scientists work together so patients get access to cutting-edge treatments as soon as they are available.

Cancer news & discoveries

Article

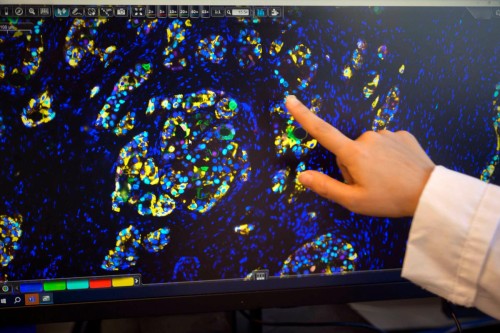

Making Progress Against Metastasis

While there has been remarkable progress in the number of people surviving with stage 4 cancer, MSK remains dedicated to research that will spur much needed advances.

Read more

Article

New Colorectal Cancer Treatments at MSK Aim To Reduce Deaths in 2026 and Beyond

Learn about the latest treatments for colon and rectal (colorectal) cancer at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Read more

Article

Reasons Why MSK Is a Leader in Stem Cell and Bone Marrow Transplants

Dr. Miguel-Angel Perales explains why MSK has continued to be a leader in the field of stem cell and bone marrow transplantation for more than 50 years.

Read more