Joan Massagué, PhD, has been featured in the pages of The New Yorker twice. Once for each of his two passions: cancer biology and mineral collecting.

In 2017, his groundbreaking work on metastasis was highlighted by Pulitzer Prize-winning author and physician-scientist Siddhartha Mukherjee, MD, DPhil.

Then last year, contributing writer Rachel Monroe bumped into him at a teahouse on the periphery of the annual Tucson Gem and Mineral Show — which bills itself as the largest, oldest, and most prestigious such event in the world. There, Monroe captured a moment in which Dr. Massagué waves off a dealer’s offer to purchase a gem embedded in calcite.

“Massagué demurred; he told me that he limits his collection to ore minerals, ‘with a special weakness for silver’ and semiprecious crystals from the Himalayas,” she writes.

If there’s one place where Dr. Massagué is in his element outside of a research lab, it’s among fellow rockhounds.

“You’re at one of these big gatherings,” he says. “You go for a bite, sit down on your own. Within a minute, someone sits down next to you. They ask, ‘What do you collect?’ That’s all you need to establish an instant connection.”

Dr. Joan Massagué: Cancer Scientist and Mineral Enthusiast

Metals Have to Come From Somewhere

Collecting minerals has been a passion of Dr. Massagué’s since his boyhood in Barcelona, Spain.

He recalls the moment his fascination was kindled listening to a teacher describe the telluric origins of metals — and therefore of all the everyday things made out of metal.

“That little story lasted maybe 15 minutes, but it was transformative,” he says. “Of course it makes sense. The aluminum in the pots and pans in my kitchen at home, the copper in electrical cables, and so forth — they have to come from somewhere.”

He went home and shared his excitement with his father — a pharmacist whose passion for the natural world manifested in birdwatching — who then gifted him a starter mineral collection for his 13th birthday. Soon the teenager was making frequent trips to the Pyrenees to dig in old mines and scratch at the exposed veins he found.

“Rough crystals, very modest, but to me they were absolute treasures,” says Dr. Massagué, who leads his own research lab while also serving as Chief Scientific Officer for Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) and Director of MSK’s Sloan Kettering Institute. “Even these many years later, I still have them.”

A Decades-Long Passion

At its most expansive, Dr. Massagué’s collection numbered over 1,000 specimens. Today, it’s down to a trim 400 — most of them measuring just a few inches. These he keeps on display at his home in glass-fronted cabinets.

At this stage in his collecting life, the specimens Dr. Massagué chooses to keep close by speak to keenly personal interests — each valuable for some unique mix of beauty, rarity, historical importance, and scientific significance. (In a 2016 supplement to The Mineralogical Record, Dr. Massagué also gives credit to his wife and daughters, who “have cheered my collecting with grace, and influenced many of my acquisitions with their good taste.”)

“Some people collect just one mineral species — quartz, for example, in all its varieties and colors,” he says. “In my case, I gravitated toward what struck me as a 13-year-old: ore minerals from which one obtains metals, like copper, silver, iron, and cobalt — and then within these, only certain subtypes.”

And like many collectors, the hobby contains a kernel of mystery. Why minerals? Why not something else: coins, stamps, seashells, orchids, baseball cards?

“There is no answer to that,” Dr. Massagué says. “People assume that because I like minerals, I must like fossils. And, well, I find fossils interesting, but it wouldn’t occur to me to collect them.”

The Unusual Charm of a Silver Thumbnail

With a little Googling, you can find specimens that have been returned to circulation with notes indicating they are ex collectione Joan Massagué. This attention to history and ownership is a feature, not a bug.

For example, Dr. Massagué recently penned an article tracing the forgotten history of one of his most prized minerals: “a thumbnail specimen of crystalized Kongsberg silver that has been gracing notable collections of larger-sized specimens for over 140 years.” (“Thumbnail” is the hobbyist category for small specimens, usually around 1 inch.)

The piece first caught his eye in 2011, when it was listed for sale at the Arkenstone, the dealership owned by Rob Lavinsky, PhD. (Dr. Lavinsky, whom The New Yorker refers to as a “prodigy of the mineral world,” is also the one who tried to sell Dr. Massagué the gemstone in the Tucson teahouse.)

“The crystal form was quite intriguing and there were some interesting historical notes,” Dr. Massagué says. “I studied it a little bit, looked it up in books, and left it at that — and the crystal sold to someone else.”

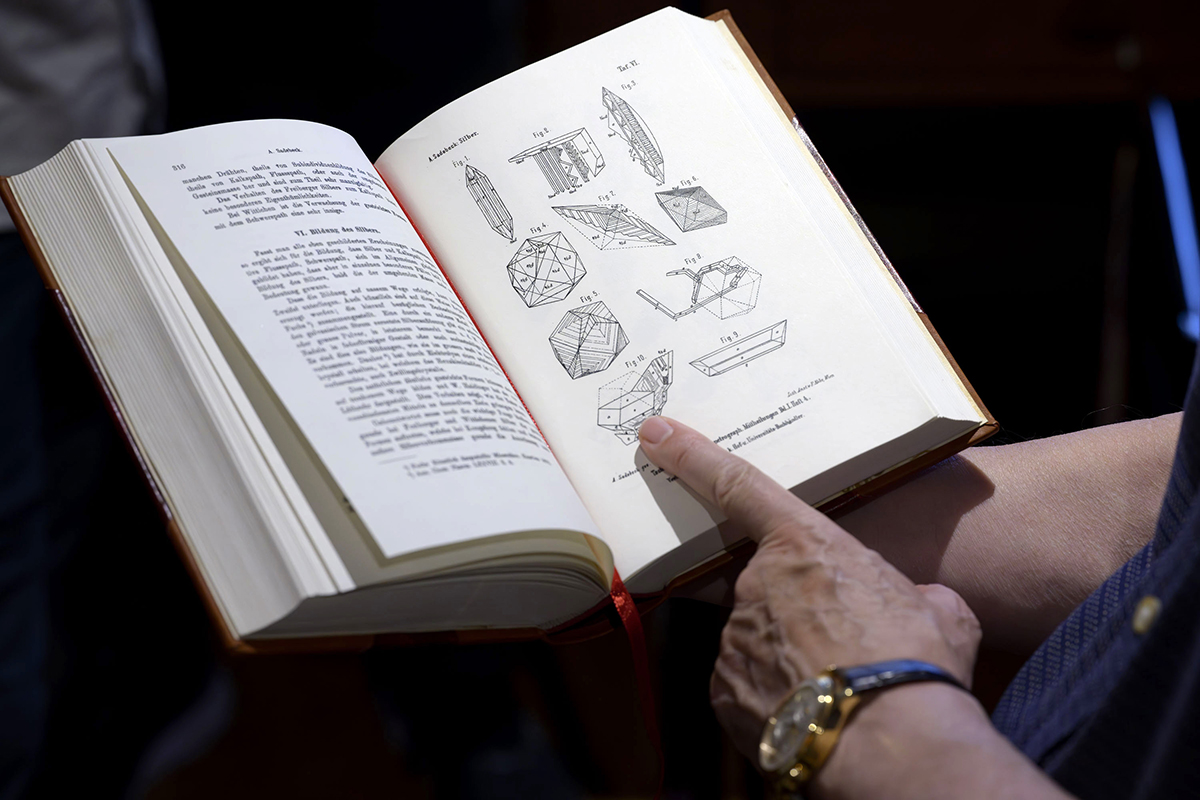

Years later, he recognized an idealized version of that same little silver curio in a book of crystal drawings from the 19th century.

“What passion is necessary for the mind to retain an image from a dozen years earlier?” he muses.

His interest reignited, Dr. Massagué called Dr. Lavinsky — who informed him that he had recently spoken with the present owner, and the owner happened to be liquidating his smaller pieces in favor of larger ones. Not only did the constellations align for Dr. Massagué to acquire the crystal, the 19th-century drawing was the key to unlocking some forgotten chapters in its history.

“It allowed me to figure out who the first owner was, in 1877,” he says. “This particular crystal out of many, many others had several paragraphs written about it.”

From there, Dr. Massagué traced the crystal’s 147-year-journey from hand to hand — including interludes with Nobel Prize–winning chemist Carl Bosch, PhD, and German banker Gustav Seligmann (after whom the mineral seligmannite is named) — and ultimately to the U.S., where it spent time in the collections of Yale University and the Smithsonian.

“Like Bosch, these various owners are not thumbnail collectors, yet they could not resist the allure of this little piece,” Dr. Massagué writes in the article.

Where Science and Mineral Collecting Meet

For Dr. Massagué, it’s never been about having the biggest or fanciest or most comprehensive set of specimens.

Both his work as a biologist and as a rock hunter involve painstaking detective work. And, more importantly, an acute focus and selectivity — knowing when to dig deep and go the extra mile, and when to let someone else seize an opportunity. There are only so many biological questions that can be answered in one career, only so many faculty members that can be recruited to a program or institute, only so much room on display shelves. Choices must be made.

“It requires patience,” Dr. Massagué says. “There’s no right or wrong. There is no one style. Just like with the Sloan Kettering Institute, I’m interested in letting the component parts help each other — so that the whole becomes more than the sum of the parts.”

In this way, both cancer science and mineral collecting are portals to larger worlds, larger conversations, larger communities of passionate individuals.

“Like scientific ideas, minerals are a window onto the history of the world,” Dr. Massagué says. “They open onto science and the history of science: minerology, metallurgy, mining, engineering. How we learned how to dig down into the earth to discern and extract its elements. Scratch the surface and you will discover many connections to the history of the economy, of war, of society, of human passion, genius, and ruin.”

And then, with a short pause, he adds, “And there’s also just the beauty. The beauty.”