In an ongoing effort to improve patients’ response to immunotherapy, MSK researchers have studied how microorganisms in the gut affect outcomes in people receiving chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T therapy for some types of leukemia and lymphoma. With CAR T therapy, a patient’s own immune cells are engineered to recognize and destroy cancer.

In a paper published March 14, 2022, in Nature Medicine, researchers from MSK and the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) reported that certain changes in the microbiota (the ecosystem of microorganisms that live on and in the body) were associated with better outcomes in patients receiving CAR T therapy. Other changes were linked to an increased risk of serious side effects.

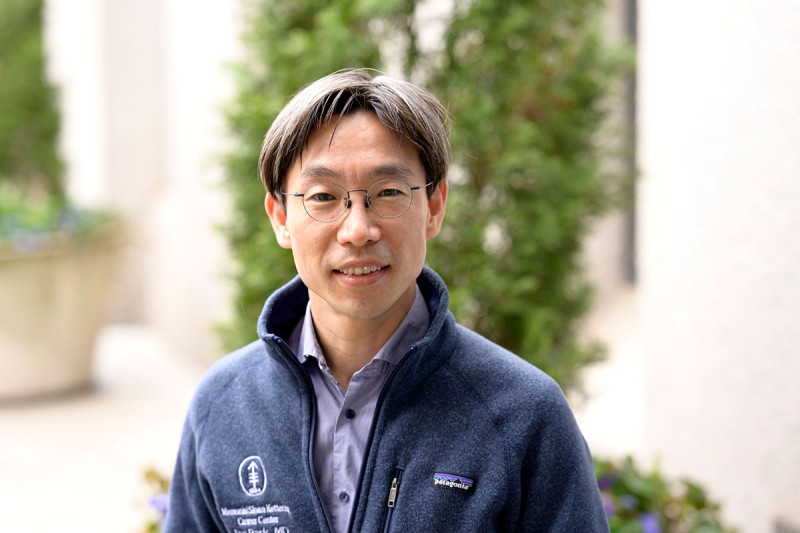

“The purpose of this study was to examine how changes in the gut microbiota may influence the clinical outcome of patients receiving CAR T cell therapy,” says MSK hematologic oncologist Jae Park, one of the study’s authors. “If we can identify the factors that are associated with more toxicity and lower efficacy, we might be able to modify them so that we can improve care.”

Making Connections Between the Microbiota and Patient Response

For more than a decade, MSK has been at the forefront of studying gut microbiota in people receiving BMTs. This initiative has been led by physician-scientist Marcel van den Brink, who was co-senior author of the new study.

“The gut microbiota is a modulator of the immune system,” Dr. van den Brink says. “Therefore, it makes sense that having a healthy gut is important for the efficacy of immune therapies like CAR T.”

For one part of the research, the investigators studied stool samples from 48 patients treated at MSK and Penn. The samples were collected before the patients received their CAR T therapy, but many of them had already received extensive treatment with chemotherapy and antibiotics. The team analyzed the samples to determine which bacteria strains were present in the gut.

After the patients received their CAR T treatment, the researchers looked for connections between particular strains and responses to the treatment — both positive and negative. They were able to identify certain classes of bacteria that were associated with the treatment being particularly effective. Other classes of bacteria were linked to a higher rate of side effects.

For the other part of the study, the investigators looked at antibiotic use and how certain antibiotics given to patients in the month before their treatment affected their overall outcomes. Some antibiotics are known to destroy healthy microbes, which allows more harmful ones to take over. This part of the study included 228 patients.

The researchers found that exposure to certain antibiotics before CAR T therapy, in particular those known as broad-spectrum antibiotics, were associated with worse survival and higher rates of toxicity. The most serious side effects from CAR T therapy are cytokine release syndrome, which causes inflammation throughout the body and high fevers, and neural toxicity, which can lead to delirium, seizures, and difficulty finding words.

Dr. van den Brink is now studying the relationship between the microbiota and the response to CAR T therapy in mouse models in his lab. “We have done a number of studies with mice looking at the connection between the microbiota and BMT outcomes,” he says. “We think that these animal models will help us learn more about the underlying mechanism of this relationship. Our research could ultimately lead to ways to manage the microbiota and improve the efficacy of CAR T therapy.”

The study’s first author was Melody Smith, a hematologic oncologist and former member of Dr. van den Brink’s lab who is now at the Stanford University School of Medicine. The other co-senior authors were Andrea Facciabene and Marco Ruella of Penn.