From left: Diana Mandelker, Jorge Reis-Filho, and Fresia Pareja have learned that a change that arises early in development can affect later cancer risk.

The underlying genetic causes of cancer have traditionally been put into one of two categories: Tumors are caused either by somatic mutations, which arise by chance over the course of a person’s life, or by germline mutations, which are inherited at birth from a parent and greatly increase the odds of developing cancer at an early age.

Researchers from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center have recently discovered that a third category of mutations linked to cancer may be more common than previously thought. This circumstance, called embryonic mosaicism, occurs when a mutation that increases the risk of cancer arises very early in development, when an embryo consists of only a few cells. As the embryo grows, those mutations will be passed to many cells in the body. As a result, the person that grew from that embryo could have risks similar to those of someone who has inherited a germline mutation from a parent, even though they have no family history. The findings were reported on December 24, 2021, in Cancer Discovery.

“In the past, this sort of mosaicism has been detected only in very rare cases, when by chance a person was found to have one of these mutations,” says Diana Mandelker, Director of MSK’s Diagnostic Molecular Genetics Laboratory and co-corresponding author of the new paper. “Our study suggests that it occurs in about 1 in 1,000 cancer patients, making it more common than we previously believed it to be.”

One reason this finding is important is that, unlike a somatic mutation that develops only in certain tissues, these mutations can be passed down to future generations if they occur early and affect the gametes (eggs or sperm). Additionally, the presence of these mutations can have implications for treatment with certain types of personalized medicine. The presence of these mosaic mutations suggests that someone may be at risk for future cancers, which can influence cancer screening.

Looking for Significance in ‘Chance’ Mutations

This research was made possible thanks to data collected with MSK-IMPACT™, a test that looks for mutations in tumors to guide cancer treatment. Unlike other genomic sequencing tests, which analyze only tumor tissue, scientists designed MSK-IMPACT to also sequence patients’ normal DNA (obtained from blood cells) for comparison’s sake. This allows doctors to detect when someone has a germline mutation inherited from a parent, rather than focusing only on somatic mutations. The new study reveals that MSK-IMPACT can also determine whether someone has a mutation resulting from mosaicism — when a significant proportion of tissues shares a common genetic trait. Mosaicism means that there are two or more genetically distinct sets of cells found within a living being.

The investigators used data from 35,310 patients who had their tumors studied with MSK-IMPACT. They looked for cancer-causing mutations in both tumor and normal DNA and then compared the two. “MSK-IMPACT gives us a unique opportunity to do this kind of research because its sequencing methods are so robust,” says physician-scientist Jorge Reis-Filho, the paper’s other corresponding author.

When someone has a germline mutation inherited from one parent, it will appear in about half of their DNA. (Recall that humans get half of their DNA from their mother and half from their father.) In the past, when mutations were detected in much less that 50% of the DNA, the origin of these mutations was unclear. That’s because these findings could be the result of mutations in blood cells or variations in the sequencing technology used. Now, using MSK-IMPACT, MSK researchers have been able to show definitively that some of these mutations in the blood actually represent mosaicism.

In this study, the investigators used MSK-IMPACT data to focus on some of the most common gene mutations associated with increased cancer risk, including those in BRCA1 and BRCA2 and the genes associated with Lynch syndrome. They also looked at a few cancer genes that are more rare.

Collaboration Enables a Closer Look at Individual Cells

Once the investigators identified patients who carried these cancer-susceptibility mutations in a fraction of their DNA that was potentially significant (about 1.5% to 30%), MSK pathologist Fresia Pareja took a much closer look at tissue samples from 10 of those patients. Dr. Pareja is the paper’s first author.

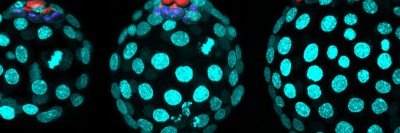

Dr. Pareja used a technique called laser capture microdissection analysis to look for the mutations in all types of tissues — not just tumors and blood cells but also cells that begin from each of the three tissue types that arise early in an embryo’s development. In many cases, the mutations were found across this entire range of tissue types, suggesting that the mutation had occurred even earlier in development (before the three fundamental tissue types had emerged). “We reasoned that the distribution of a mutation across normal tissues would indicate the timing of when the mutation arose,” she explains. “By using advanced mathematical models, we have found that these mutations likely occurred in the first five cell divisions of embryogenesis.”

The pathology team collaborated with Anna-Katerina Hadjantonakis, Chair of the Developmental Biology Program in the Sloan Kettering Institute, who is an expert in embryonic development. Together, the investigators determined that these cancer-causing mutations occurred very early in development, when the embryos consisted of less than a dozen cells. When the embryo later divides and creates more specialized tissues (like the different cell types found in muscles, nerves, and organs), the cancer-causing mutation gets carried along and distributed throughout the body.

The investigators took the research one step further to confirm that the cancer-susceptibility mutations observed in the tissues were actually important to the formation of these cancers. They did this by looking at genomes of tumors developing in individuals with mosaic mutations, which were found to have the genomic “scars” expected to be present in cancers caused by a mutation inherited through the germline. These analyses established a causal relationship between the mosaic variants and the development of the respective cancers.

The new study suggests that more patients could benefit from certain treatments — but only if their mosaicism is detected. For example, people with inherited BRCA mutations respond well to targeted therapies called PARP inhibitors. Those with Lynch syndrome respond well to immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors.

Applying Discoveries to Patient Care

Overall, the researchers found that these mutations due to mosaicism occurred in 36 patients, or about 1 in 1,000 cancer patients tested. This number is small, but not insignificant. “We could only make a discovery like this at MSK, where so much data is available because of MSK-IMPACT,” Dr. Mandelker says.

Based on the discoveries reported in this paper, the members of MSK’s Diagnostic Molecular Genetics Laboratory plan to look for mosaicism in every new patient who has testing with MSK-IMPACT.

“Going forward, we will soon be able to detect this mosaicism in real time and include it in the patient’s clinical report,” Dr. Reis-Filho says. “Because we are the largest cancer center that systematically sequences normal DNA in addition to tumor DNA, we are in a better position to make sure every patient gets the best treatment.”

By sharing their findings, Drs. Reis-Filho and Mandelker and their colleagues hope to expand awareness of this situation beyond the walls of MSK. They also plan to continue their studies on mosaicism and its effect on cancer susceptibility.

- MSK researchers are studying embryonic mosaicism, which occurs when a mutation that increases the risk of cancer arises very early in development.

- They have found that people with this condition may carry the same risk for future cancers as those who have inherited mutations from a parent.

- This finding can have implications for both treatment and screening.

- It was made possible thanks to data from MSK-IMPACT, a screening test that analyzes both cancer and normal DNA and compares the two.