Stem cells are defined by their ability to differentiate into other, more specialized cell types. When one stem cell divides into two (which are then called daughter cells), three things can happen to the new cells: Both cells can continue being stem cells, both cells can differentiate into a new cell type, or the cells can go their separate ways, with one maintaining the properties of a stem cell and the other becoming something new.

“It may be surprising, but as much as stem cells have been studied, we don’t know much about how they make this commitment when they divide,” says Michael Kharas, who is in the Sloan Kettering Institute’s Molecular Pharmacology Program. Dr. Kharas led a team from SKI, in collaboration with investigators at Weill Cornell Medical College, that discovered new details about how dividing stem cells choose what to become. Their findings were published August 13 in Cell Reports.

Dr. Kharas’s lab uses human and mouse blood (hematopoietic) stem cells to study how certain types of leukemia develop.

Knocking Out an Important Protein

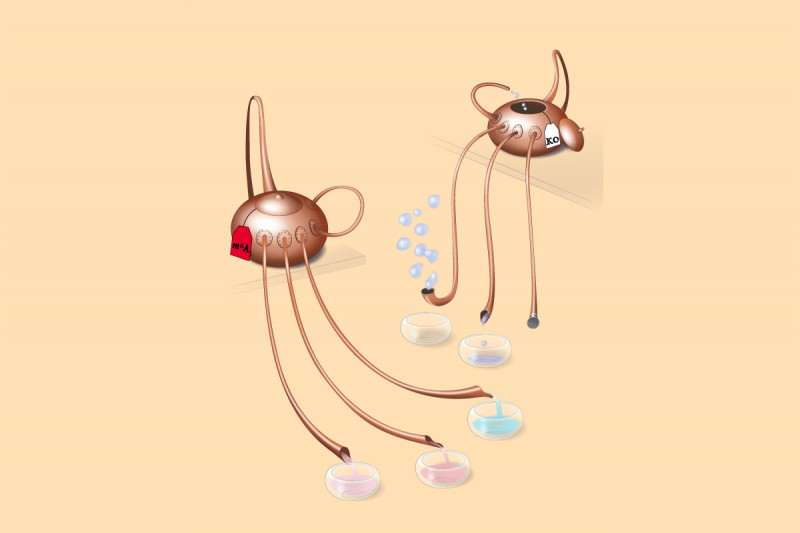

When both daughter cells are the same cell type, this is called symmetric division. That’s true whether they continue being stem cells or become something new. When one cell stays a stem cell and the other differentiates, it’s called asymmetric division. This happens about 30 percent of the time.

“The beauty of asymmetric division is that you’re maintaining your stem cell numbers,” Dr. Kharas explains. “If every time a stem cell divides, it loses its identity as a stem cell, you will eventually deplete all the stem cells. But if all the cells remain stem cells, you’ll never get the variety of cell types you need to form an entire blood system.”

Previous work in the Kharas lab has focused on a protein called MUSASHI-2. The researchers found that when MUSASHI-2 is knocked out in blood stem cells, the cells lose their “stemness.” They are more likely to differentiate and become nonstem cells. Additionally, they have less of the asymmetric type of division.

In the new study, the investigators — led by first authors Yuanming Cheng and Hanzhi Luo, of Dr. Kharas’s lab, and Franco Izzo from Weill Cornell — focused on a different protein: METTL3. Both MUSASHI-2 and METTL3 are RNA-binding proteins, but the METTL3 protein is the key enzyme that can add chemicals called methyl groups to specific RNA nucleotides. This process is called methylation, and it decorates RNA with marks called m6A.

Ultimately, this helps regulate the stability of the RNAs and the efficiency of protein production. Targeting RNA-binding proteins has been identified as a new approach in the development of drugs for leukemia.

Taking a Closer Look at Stem Cells

To study the role of m6A, the researchers compared the blood-forming systems of mice that had METTL3 knocked out and those that did not, to see how blood development was affected. They found that the mice without the protein seemed to have an accumulation of blood stem cells, suggesting that the cells were unable to become more specialized cells.

To get a better look at what was going on, the lab of Dan Landau at Weill Cornell studied the cells with a type of analysis called single-cell RNA sequencing (RNA seq). RNA seq enables researchers to determine which genes are being expressed, or turned on, in cells. This revealed that there were actually fewer stem cells than originally thought. But some of the cells seemed to be stuck in an intermediate state between stem cell and differentiated cell that the scientists had never seen before.

“These stem cells had reduced ability to symmetrically differentiate. Based on these findings, we believe that METTL3 — and therefore, RNA methylation — controls this specific type of division in hematopoietic stem cells,” Dr. Kharas notes. “This research suggests a general mechanism for RNA methylation in controlling how stem cells regulate their fate when they divide.”

Implications for Cancer Treatment and Beyond

Dr. Kharas explains that there are two main implications for this new finding.

Many researchers and pharmaceutical companies are focused on developing new leukemia drugs that target the RNA methylation process. “It’s important to know how these drugs might work and what unintended consequences they may have,” he says.

But perhaps more interesting to the researchers who worked on the project are the implications for understanding the division and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells.

“Now that we have identified this new population of cells in our lab, we may be able to use them as a model to understand the intricate steps that happen when a stem cell decides to differentiate,” Dr. Kharas concludes. “It may eventually provide a new approach for growing large numbers of stem cells for the development of cell therapies.”