The Immune System and Cancer Vaccines

One way our immune system protects us is by ridding our bodies of altered cells that could lead to cancer. But exactly how and when does our immune system sense cancer? How do tumors evolve to avoid being detected? And how can a better understanding of this process help develop better cancer treatments?

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) computational biologist Benjamin Greenbaum, PhD, is looking for answers to these important questions. He is the co-director of Neoantigen Discovery for The Olayan Center for Cancer Vaccines at MSK, a hub for cancer vaccine discovery and innovation. The center’s computational efforts, which have also received funding from The Tow Foundation and are led by Dr. Greenbaum, are essential to designing effective cancer vaccines.

What do viruses and cancer cells have in common that triggers the immune system?

Our immune system senses the presence of pathogens — molecules that are recognized as being different from our normal “self.” We typically think of pathogens as being something from outside the body, like a circulating virus such as the flu or COVID. However, we and others have found that normal cells that begin to turn cancerous can also present molecules that the immune system recognizes. Like pathogens, cancers can also disguise themselves by mimicking what is “self” to survive. That’s part of why the immune system must strike a balance between going after abnormal cells while avoiding attacking normal cells.

The focus of my lab is to understand what exactly the immune system sees as non-self in a cancer cell or virus. How does a cancer cell respond when it’s detected by the immune system? Does the cancer cell then drive off in a certain direction, like a criminal taking an escape route to elude the authorities? Can we predict how this might happen and what the likely route taken will be?

Answering these questions will help guide new therapies that harness immune recognition of cancer — that includes cancer vaccines.

How does the immune system respond to a pathogen?

The immune system has two main arms: innate and adaptive.

- The innate immune system recognizes broad molecular patterns, such as molecules that certain RNA viruses generate as they replicate. (Molecules that trigger an immune response are called antigens.) The innate immune system is often the first line of defense against a threat, but it does not recognize specific antigens, such as those we target with vaccines. An immune defense based only on the innate arm is not enough because specific pathogens we encounter can evade innate immunity.

- When the innate immune system recognizes a pathogen, it communicates with the adaptive immune system to essentially take over. The adaptive immune system can recognize specific antigens and commit them to memory for a long time. Adaptive immunity can give us lifelong protection against disease after being infected or being primed by a vaccine, like for measles. A vaccine educates the immune system about antigens it might encounter in the future.

Why is it hard for the immune system to detect cancer?

The immune system evolved to recognize pathogens that are non-self. But cancers arise from normal cells and therefore they often don’t look as threatening to the immune cells as, say, a virus-infected cell. Understanding when and why immune cells can recognize cancer is one of the main focuses of our lab.

What are “neoantigens”?

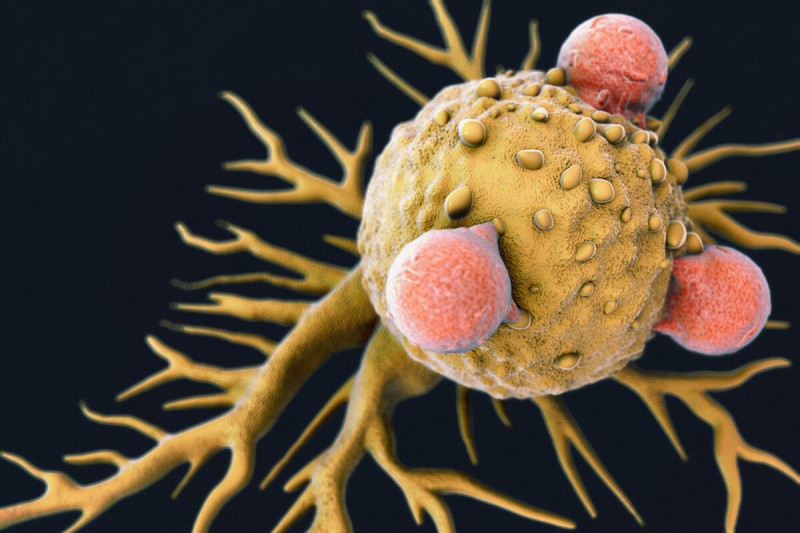

Over the past few decades, we have learned that one of the main ways the immune system senses cancer is by recognizing mutated proteins — antigens — found on the surface of cancer cells. These are fundamental byproducts of cancer evolution. Cancers accumulate mutations as they grow and spread, and some of these genetic errors will generate mutated proteins that are not normally found in the body. We call these new antigens “neoantigens.” They can serve as red flags to the immune system that a cell is no longer self and needs to be eliminated.

Unfortunately, the immune system sometimes does not detect neoantigens because they do not look different enough from normal cells. But that is not the only problem. Nobel Prize-winning research, some of it conducted at MSK, found another reason the immune system holds back from attacking cancer: It is inhibited by immune checkpoints, which act as brakes on the immune cells to keep them from attacking healthy tissues. However, these brakes can be released with drugs called checkpoint inhibitors. It then becomes possible for the immune system to more easily recognize some of the neoantigens in cancers.

This discovery has important implications for developing cancer vaccines, which can further direct the immune response to specific neoantigens. We can make personalized immunotherapy treatments effective if we know which specific neoantigens to pick as the target.

What are you learning about the interaction between the immune system and cancer cells?

We initially set out to understand why the immune system recognizes some neoantigens over others in patients who received immunotherapy. Specifically, we started looking at the “neoantigen quality” or the characteristics a neoantigen has that allow immune recognition. We collaborated with MSK surgeon-scientist Vinod Balachandran, MD, to investigate this in a unique group of people with pancreatic cancer who beat the odds and survived this deadly disease for many years.

In 2017, we published research in Nature showing these long-term pancreatic cancer survivors have tumors that are especially immunogenic — their tumors are spontaneously recognized and attacked by T cells, the strongest immune cells. Interestingly, in these patients, T cells targeting the cancer’s specific neoantigens were found patrolling the body even a decade or more after treatment. This was surprising because pancreatic cancer was long thought to lack immunogenic neoantigens and to be insensitive to immunotherapy.

In a follow-up study, we showed that the immune system affects the evolution of pancreatic tumors by recognizing immunogenic neoantigens. This confirmed certain neoantigens are very important from an immune perspective. Even though the neoantigens may not necessarily drive the cancer themselves, they can attract immune attention that may snuff out recurrence. This supports the idea that we can make an immunotherapy that works in pancreatic cancer.

Bolstered by these findings, Dr. Balachandran and MSK colleagues launched a clinical trial in 2019 to test a vaccine using messenger RNA (mRNA) in people with pancreatic cancer. In this trial, patients had their tumors removed surgically, and their cancer cells were used to custom design a vaccine that targets unique neoantigens expressed in their tumor. This study is investigating whether a vaccine can stimulate the production of immune cells that recognize specific neoantigens. So far, the answer appears to be “yes” — the next question is whether a vaccine-induced immune response can keep the cancer from returning after surgery beyond the typical prognosis. While early results are encouraging, we need more data from a larger group of patients.

What strategies are being used to improve cancer immunotherapies, including cancer vaccines?

Most cancer immunotherapies, including the pancreatic cancer vaccine, work by harnessing the adaptive immune system to generate long-term protection. But only a small percentage of cancer patients have benefited so far from immunotherapy, so we are continuing to investigate all parts of the immune system.

That’s why we are also studying how the innate immune system responds to cancer. Because the innate immune response is more general, a therapy based on it could benefit more cancer patients or boost a therapy that targets the adaptive immune system. My lab is trying to shed more light on how the innate immune system interacts with cancer as well as with the adaptive immune system.

How does the innate immune system sense cancer?

When a normal cell starts turning into cancer, its DNA and RNA machinery can get messed up in ways that present like a viral infection (often described as “viral mimicry”), which triggers the innate immune system. One example is repetitive DNA, where certain genetic sequences repeat over and over. Some of these repetitive sequences come from transposons, also known as “jumping genes,” which can move around in our DNA. These elements literally make up around 40% of our genome, though a much smaller fraction remain functionally active.

In some cases, for instance, transposons form double-stranded RNA, a type of molecule often produced when viruses replicate. The innate immune system recognizes double-stranded RNA as a warning sign and reacts to fight off the threat. However, cancer cells can adapt. We have studied recently how they might destroy the double-stranded RNA before the innate immune system notices, helping them escape detection, in work led by postdoctoral research scholar Siyu Sun, PhD, in our lab.

We think one specific repeat, called LINE-1, is especially important. LINE-1 comes from ancient virus-like elements that became part of human DNA over millions of years. Normally, it stays inactive, but in cancer, it can turn on and start to replicate in our DNA. We have discovered that when a key cancer-fighting gene, p53, is mutated — which happens in more than half of cancers — LINE-1 is far more likely to become active.

We recently studied a key enzyme, ORF2p, produced by LINE-1 that is essential for its replication. By understanding the structure of ORF2p and how it interacts with the immune system, we hope to develop drugs that can target this enzyme — potentially stopping cancer from avoiding immune attacks.

How do these findings fit together into ways to improve cancer immunotherapies, especially cancer vaccines?

All immunotherapy depends on the immune system recognizing cancer. So, if we can figure out generally what the immune system is sensing — and how it affects how cancers grow, spread, and adapt — we will have a much clearer idea of how we can intervene therapeutically. Understanding all the elements at play in the immune response to cancer gives us more to target. What are the best antigens to target? Are those antigens shared across many patients? Are there targetable antigens we are missing? Can we identify the T cells that target specific antigens? There are many questions to answer, which makes this an exciting field.

For cancer vaccines, this means finding the best possible antigens but also measuring how T cells respond to vaccination. It is important to send a strong signal to the immune system while also anticipating how the cancer may adapt and evolve to evade the immune system. The research in my lab and others at MSK will help us cast the widest possible net, and with The Olayan Center for Cancer Vaccines at MSK, we will be able to rapidly test new concepts to accelerate new cancer immunotherapies.