Molecular biologist John Maciejowski joined the faculty of the Sloan Kettering Institute in 2017 after completing his doctorate at MSK’s Gerstner Sloan Kettering Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences and his postdoctoral training at The Rockefeller University. He was in GSK’s first matriculating class in 2006 and graduated in 2013.

Dr. Maciejowski studies chromosome instability and its role in cancer. In a May 2021 interview, he discussed how he got into science and what his lab has been focusing on lately.

When did you discover an interest in science?

It wasn’t until near the end of college at New York University. I was a math major, but I saw an opportunity to get a work-study job in a biology lab, basically washing and sterilizing dishes. I got interested in biology through that and took an intro to biology course late in college. Then I continued on in that lab as a tech for three years after graduating. I read independently, went to a few conferences, and thought: This seems much better than whatever I would’ve done with my math degree.

Do you come from a scientific family?

Not at all. Actually, I think I’m the first one in my family to graduate from college. My parents are Polish immigrants. My dad worked as a butcher in the Meatpacking district here in Manhattan and later as a handyman in Queens. My mom had a few different jobs: She worked in the Bronx courthouse as a clerk, then as a bank teller. She was also a birth photographer for a bit.

Did you intend to stay in New York City this long?

Not really, it just worked out that way. For my postdoc, I looked at places as far away as Switzerland. And for my first faculty position, I considered the UK and Seattle. I was open to leaving at every stage of my training, but the best opportunities for science were always here in New York.

Then as I got older, I had more and more roots here. My wife — a former GSK student herself — was very happy in her job. We now have an 18-month-old daughter.

But the science was a big part of it. I remember coming back to MSK for the faculty interview. Part of the interview process includes giving a “chalk talk” where you present all your hopes and dreams for the next five or 10 years. Everyone here really challenged me on my ideas, and I loved that.

What’s one topic your lab is working on right now?

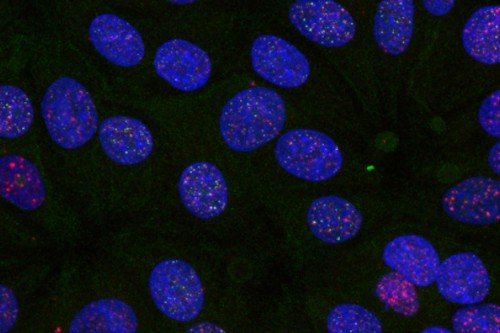

We’re really interested in how abnormal chromosome compartments in a cell can contribute to cancer. Our window into the process is through the study of micronuclei, which are membrane-bound compartments that contain chromosomes or chromosome fragments that didn’t segregate properly during cell division, and so remain separate from the rest of the genome. Micronuclei are found in many different cancer types.

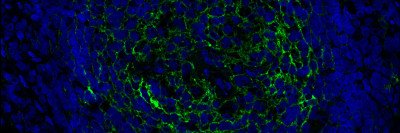

There are two potential ways cancer cells can benefit from micronuclei. On the one hand, they may promote genomic rearrangements that can fuel cancer growth. There may also be cancer-promoting effects that result from the immune response that follows micronuclei rupture. My colleague in the Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program Sam Bakhoum has shown that micronuclei rupture promotes metastasis.

When the micronuclear envelope ruptures, it triggers an immune sensor called cGAS. This sensor basically surveils the cell for double-stranded DNA, which is commonly associated with viral infections. If it finds any double-stranded DNA, it activates an immune response. A DNA-cutting protein called TREX1 is known to block cGAS activation by clearing the cell of loose double-stranded DNA.

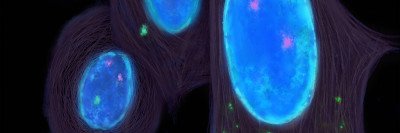

Eleanore Toufektchan, a postdoc in my lab, developed methods to purify micronuclei and found that TREX1 was glomming onto micronuclei that had ruptured. We thought that was neat because TREX1 is usually found in a completely different part of the cell, called the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). We wanted to understand how it was getting there. The simple model would be that when the nuclear envelope breaks, the micronuclei chromosomal DNA is exposed to the liquid inside the cell, and TREX1 says, “Hey, DNA, I like that. I’m going to bind.” But we made mutations to kill TREX1’s ability to bind to DNA, but it still rapidly traveled to the micronuclei. That was a surprise.

Then we made mutants where we lopped off TREX1’s ability to interact with the ER and that completely killed its ability to home to micronuclei. When we re-tethered TREX1 to the ER, this restored the localization to the micronuclei. There’s something important about the attachment to the ER, which we don’t yet fully understand.

In the past, TREX1 has been studied in the context of immune disease. Mutations in TREX1 are associated with a really terrible immune syndrome called Aicardi-Goutières as well as other immune syndromes like lupus. We suspect that these mutations may interfere with TREX1’s ability to block cGAS activation in micronuclei, and perhaps in other structures that may form in healthy tissue, and this leads to inflammation that contributes to disease. We published these results in Molecular Cell in February 2021.

What’s something that you would want prospective grad students or postdocs to know about your lab?

The people I look for don’t need to have had the biggest paper, as long as they are driven by curiosity and are willing to take a multidisciplinary approach. I think that one of the unique aspects of our lab is that we’re working on a variety of topics. At journal club in any given week, we could be covering genomic integrity, cancer, or immunology. For me, and I hope for people in the lab, what I enjoy is continuing to learn — just continuing to be a student of science. I’m looking for other people who are willing to be forever students in that way.