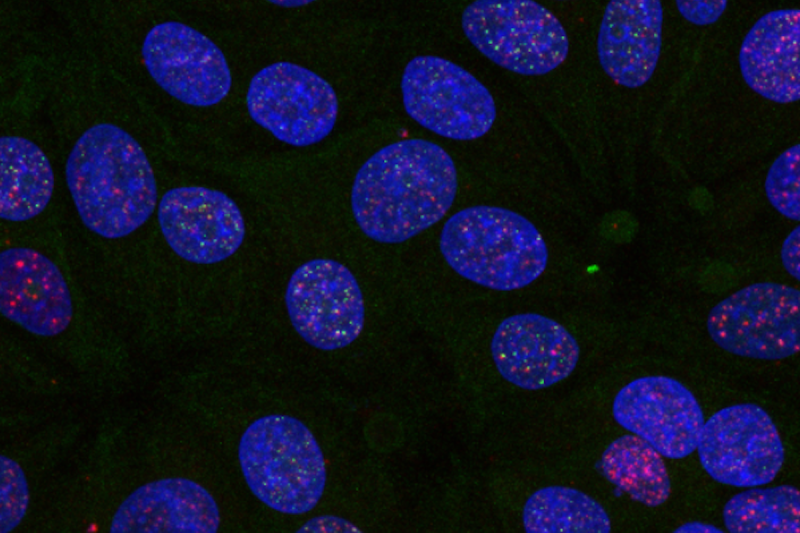

In the image above, the red dots represent proteins gathering at a break in a cell’s DNA. The proteins act like lifeguards, springing into action only when DNA needs repairing.

The first microscope was invented almost 500 years ago, when two Dutch scientists placed lenses in a tube and found that they could magnify and observe tiny objects. Technology has come a long way since then. Today, microscopes can yield multicolor images that give scientists insight into what is happening inside cells.

One way microscopes have proven useful is in studying damage to DNA. Our DNA is harmed several thousand times per day, often simply by our surroundings — for example, when we inhale secondhand smoke or are exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light from the sun.

The DNA of cancer cells can be broken apart too. The photo above depicts cancer cells that have been exposed to x-rays. The DNA contained in the cells’ nuclei are stained by a chemical called DAPI, which appears blue under UV light. In some of the cells’ nuclei, there are red dots that represent proteins gathering at a break in the DNA. Without these chemically stained proteins, it would be impossible to see DNA breaks under a microscope.

Just as a lifeguard keeps an eye on swimmers from a chair and springs into action only if there is a problem, a protein called ƴH2AX rushes to a DNA break very soon after it occurs. (This protein is what appears in red in the image above.) After it detects the damage, this “lifeguard protein” signals for help.

One important part of this response is that the cell temporarily stops dividing so that it has time to fix the mistake. At the same time, other proteins are recruited to the break to help hold the ends together. Eventually, the gap in the DNA is filled.

Repair proteins also are brought to the site of damage to patch up the broken DNA. One of these proteins is RAD51, which is shown in green in the image above. RAD51 is crucial in repairing DNA breaks because it helps the cell find out what genetic information was lost and reconstruct it.

Cells have several ways to repair a break in their DNA. In most situations, they can correct it quite effectively and resume their normal life cycle. When the repair machinery doesn’t work — when the lifeguard doesn’t jump into the pool to save the drowning swimmer — various neurological conditions or cancer can result. In late 2014, the first drug targeting DNA repair (called olaparib or Lynparza™) was approved to treat people with ovarian cancer. This drug and similar ones are currently being evaluated for breast cancer and other types of cancer with DNA-repair-related mutations.

If we were to look at the cancer cells in the image above a few hours later, the red dots would have mostly disappeared. As the damage gets repaired, the lifeguard returns to its chair to keep watch. The green dots (the repair proteins) take a little longer to disappear but eventually they will become undetectable as well.

Using microscopes and chemical stains to monitor how proteins react to DNA damage and DNA repair can help researchers understand how well a cell can cope with this disruption. Ultimately, it may be useful for studying the role of DNA repair in cancer and cancer therapies. This includes the effectiveness of drugs that are designed to influence these causes.