Choosing the best approach for prostate cancer can be a tough call. Small tumors typically grow slowly and may never cause problems. Many patients with low-risk cancers now forego immediate treatment for close observation, an approach known as active surveillance. For those who opt for treatment, complications from surgery or radiation can impair urinary control and sexual function.

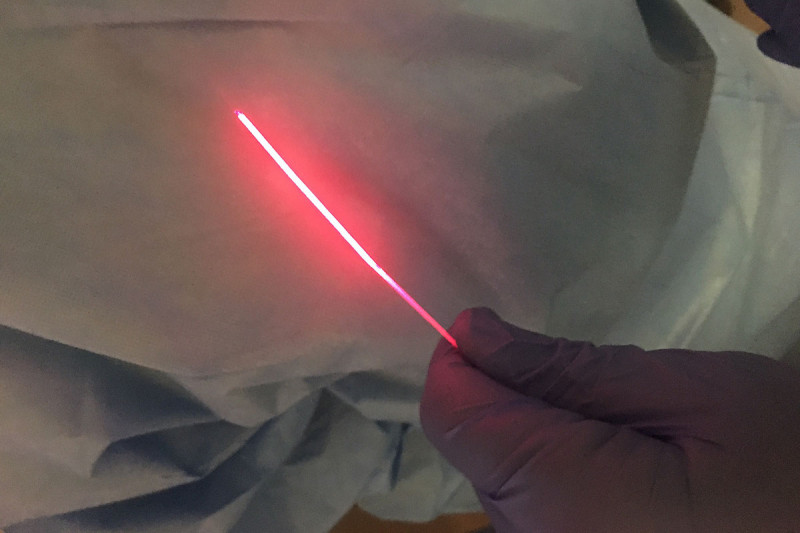

Memorial Sloan Kettering specialists are investigating a technique that could destroy most small prostate tumors with virtually no ill effects. Called vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy (VTP), the technology uses a light-sensitive drug that can be injected into the bloodstream. The drug, called Tookad®-Soluble, activates when it encounters a certain wavelength of laser light, which is emitted from optical fibers inserted into the prostate.

Once activated, the Tookad drug generates unstable molecules called free radicals. These destroy tumor cells and the small blood vessels that feed them. The approach already proved effective in treating low-risk prostate cancers in a small number of MSK patients and in a large study in Europe. Roughly 80 percent of the tumors were destroyed with little to no side effects.

This month, a phase II clinical trial led by urologic surgeon Jonathan Coleman will launch at MSK to investigate whether VTP can be used to treat people with slightly larger, intermediate-risk prostate cancers.

“We hope to show that this therapy can possibly prove itself as an alternative to more-established treatments, like surgery and radiation therapy, for intermediate-risk cancers,” Dr. Coleman says. “By selecting the right patients, we may be able to treat a large number of tumors effectively with a greatly reduced risk of complications that lower quality of life.”

Dr. Coleman explains that in some cases, VTP could also be an alternative to active surveillance. Some patients under active surveillance see their cancer progress to the point where it needs treatment by surgery or radiation. Having the option to destroy the tumor earlier with minimal ill effects would prevent the need for more-aggressive treatment down the road.

Light Therapy with Light Effects

People receiving VTP are brought to an operating room and put under mild sedation, similar to that given for a colonoscopy. Doctors use an ultrasound probe to guide the placement of an array of very thin optical fibers — typically eight or fewer — into the prostate tissue. Then they start the intravenous flow of Tookad, which is derived from chlorophyll found in plants and bacteria.

Ten minutes after starting the drug, the doctors turn on the fibers. The light is emitted at a wavelength that activates the drug to generate short-acting free radicals that destroy cells in the immediate area. After another 20 minutes, the light is turned off, the fibers are removed, and the patient wakes up and is taken to the recovery room. The patient usually remains in a darkened room for six hours, since they have to stay out of light until the drug leaves the body.

“Then they can get up, walk out the door, and go home,” Dr. Coleman says. As a precaution, patients are given detailed instructions to avoid direct sunlight for two days.

Most people receiving VTP have little to no sensation that they have even been treated. In fact, the first person Dr. Coleman treated said he felt nothing at all. Dr. Coleman was convinced he had done the procedure wrong, and Tookad had not been activated inside the body. “And yet, when we looked at the MRI a few days later, it was very dramatic to see the change in the prostate,” he says.

Intense Interest in VTP Clinical Trial

The new MSK trial will study the effectiveness of VTP in 50 people with intermediate-risk prostate cancer — those with a Gleason score of 7 (3+4). Three months after treatment, they will be biopsied to see if any cancer is left. If there is, they can receive a second treatment if needed. The entire group will be evaluated again one year after treatment to look for any remaining disease.

Dr. Coleman says that people have been eager to enroll — there are already 30 people on the waiting list — so the researchers will be able to get answers without much delay. “For several months, we’ve had people coming into our clinics, knowing that this trial is starting, and wanting to be put onto a list. Full accrual should be done by the end of the year.”

Meet Urologic Surgeon Jonathan Coleman

He cautions that VTP won’t work for around 20 percent of people who receive it, and some may require surgery or radiation afterward. Nonetheless, he expects the clinical trial to show that VTP is very effective. Its availability as a treatment option could be practice changing.

“People with intermediate-risk tumors might avoid surgery or radiation,” he says. “For those with lower risk, I have many patients who say, ‘If you have a technology with an 80 percent success rate, with a negligible impact on my quality of life, why wouldn’t I just do this to get the tumor out of the way and mitigate my risks instead of worrying about the cancer getting worse and requiring treatment?’”

Dr. Coleman is quick to note that it is still too early to assess the lasting results of this treatment. There has been no long-term follow up, and it has only been performed in highly selected patients with small, well-defined tumors. Not everyone is a candidate for VTP.

Broad Potential: Treating Other Cancers with VTP

VTP has potential for treating other cancer types as well. MSK is collaborating with the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel to begin clinical trials testing the technology in bladder, esophageal, breast, and pancreatic cancers.

This work is based on a large, collaborative basic science research program led by Dr. Coleman at MSK and Professor Avigdor Scherz at the Weizmann Institute, which produced exciting new discoveries. Many labs and researchers have been involved and helped propel this work forward, including physician-scientists Jedd Wolchok and David Solit at MSK.

“One of the reasons we have an intense interest in this technology at MSK is that we see tremendous opportunity for developing its use for a variety of very difficult cancers,” Dr. Coleman says. “Even if it did not provide a cure, VTP could shrink tumors enough that they could be surgically removed.”

He credits the dedicated work of MSK senior research scientist Kwanghee Kim and strong philanthropic support from the Thompson Family Foundation for enabling VTP to be moved into trials so rapidly. “It’s difficult to get funding for innovative technologies,” Dr. Coleman says, “so it is critical when private funders step in to propel treatments forward.”