The cells weren’t supposed to turn pink, Charlotte Friend thought to herself as she stared into a glass tube on her lab bench at Mount Sinai hospital in 1971.

Dr. Friend, a microbiologist, had been experimenting with a virus that caused cancer in mice. The virus infected mouse cells then hijacked the cells’ genetic machinery, leading to leukemia.

In this particular experiment, she first soaked the cells in a chemical called DMSO. She hoped to make the cells more porous, enabling more virus particles to enter. A few days later, the normally clear solution of leukemia cells had turned bright pink.

Dr. Friend phoned the one person she thought might have some insight.

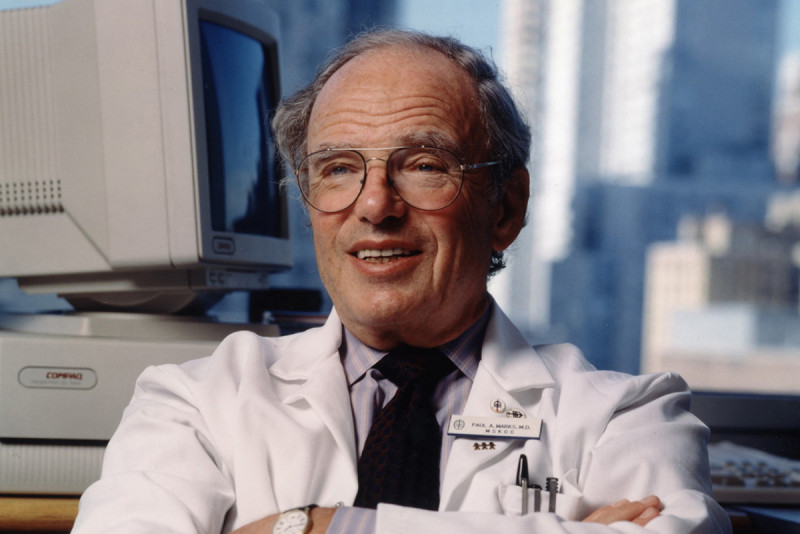

“What human proteins are red?” she asked Paul Marks, a professor of clinical pathology at Columbia University whom she knew to be an expert in the genetics of blood disorders.

“There’s only one,” Dr. Marks replied.

Birth of a New Cancer Treatment

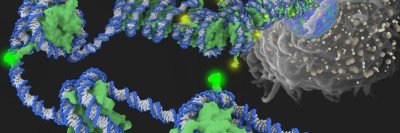

Red blood cells are red because they make hemoglobin. Apparently, DMSO had caused the leukemia cells to switch on their production of this protein. Not only that, DMSO also curbed the cancer cells’ rapid division. As Dr. Marks later wrote, DMSO had “coaxed the monster back into a benign state.”

Though tentative, and still surrounded in much mystery, this was the moment when a new approach to treating cancer was born. Rather than kill cancer cells with toxic drugs — the approach of many chemotherapies — scientists would try to steer wayward cells back onto a normal developmental course.

Thirty years later, these fledgling observations would result in the FDA approval of vorinostat (Zolinza®), a drug used to treat certain types of lymphoma. Vorinostat is one of the first so-called epigenetic therapies for cancer. Epigenetic refers to changes in gene expression that are not due to changes in the DNA sequence. The active component in vorinostat, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, is structurally related to DMSO.

In between the milestones of Dr. Friend’s initial discovery and the approval of vorinostat, many of the foundations of modern cancer biology were built, with Dr. Marks playing a key role as architect.

Building Cancer Science

Inspired by the questions lurking in that tube of pink cells, Dr. Marks decided that the problem of cancer needed to be tackled through discoveries in basic science. Only when we understood the inner workings of normal cells, he reasoned, would we be fully able to intervene thoughtfully in those processes to tame cancer. This was in contrast to previous approaches to treating cancer that largely revolved around trial and error.

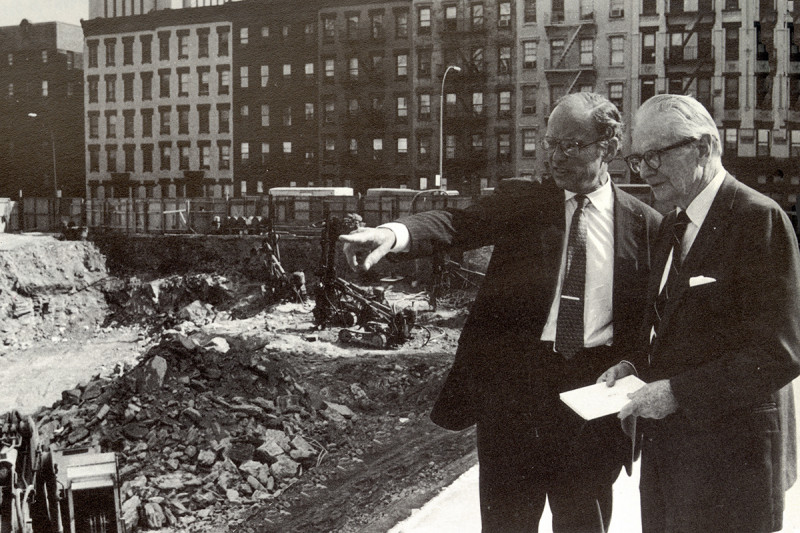

Dr. Marks began looking for ways to transform oncology into a research-driven science. He got his chance when, in 1980, at the request of MSK Board Chairman Laurance Rockefeller, he assumed the reins of MSK’s presidency. He held that position for the next 19 years, until his retirement.

One of Dr. Marks’s first actions as president was to recruit to the Sloan Kettering Institute (SKI) some of the most promising young scientists of the time. Among them were James Rothman, Nikola Pavletich, Dinshaw Patel, Jerard Hurwitz, Ora Rosen, Ken Marians, Joan Massagué, Maria Jasin, Kathryn Anderson, and Mark Ptashne.

This cast of rising stars had the bona fides, in Dr. Marks’s eyes, to investigate the problem of cancer in the way that was most likely to yield results: from the inside out. “Most of the answers to cancer lie down on the level of the genes, in our understanding of how cells differentiate and divide,” he once said.

Dr. Marks’s views on cancer research were shaped in part by his own introduction to basic science, through time he spent in the Pasteur Institute lab of the Nobel Laureate Jacques Monod in the 1960s. He wanted to bring that perspective to Sloan Kettering.

“He definitely saw the importance in having a very strong basic-science component to this institution,” says Thomas Kelly, a former Director of SKI and now a professor in its molecular biology program. “His vision was to foster the development of SKI by bringing in leaders in their fields. It was a small group of investigators, but the impact on science was very high.”

Through his efforts, Dr. Marks helped to set MSK — and by extension the wider field of oncology — on a more scientific course. The particular field of epigenetics, which Dr. Marks helped to establish through his work on vorinostat, is now thriving at MSK.

Paul Marks’s Lasting Legacy

Dr. Marks influenced the cancer establishment in yet another way: as a teacher. For many years he taught the clinical pathology course to medical students at Columbia. One of his students was Harold Varmus, who would later win — along with J. Michael Bishop — a Nobel Prize for discovering the cellular origin of cancer-causing genes, or oncogenes.

“Paul Marks made a special impression on me in his lectures,” Dr. Varmus recalled in his memoir, The Art and Politics of Science. “As Dr. Marks’s lectures made clear, such changes in DNA (mutations) could cause disease when they affected physiologically important proteins.”

Dr. Varmus would succeed Dr. Marks as president of MSK, taking the helm in 2000. True to the influence of his mentor, he continued the legacy of supporting innovative basic science.

In recognition of his many contributions, including his support for young scientists, the Paul Marks Prize for Cancer Research is now given every other year to investigators who have made important contributions to cancer research early in their careers. MSK’s Board established the prize at the time Dr. Marks retired. His face appears on the medal.