Immunologist Justin Perry came to the Sloan Kettering Institute (SKI) in 2019, after completing his graduate studies at Washington University in St. Louis and a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Virginia. His lab studies cell death and how the body deals with the millions of cells that die every day and need to be eaten by cells called phagocytes. When this eating process goes awry, autoimmunity or cancer can result.

Dr. Perry was recently awarded a 2021 National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director’s New Innovator Award (DP2) for his research. He is also a 2021 Pew Biomedical Scholar.

Here, Dr. Perry discusses his journey from a childhood in rural Alaska to his career as a scientist in New York City.

How did you become interested in science?

I was interested in psychology for as far back as I can remember — probably related to growing up in Alaska, where there’s a lot of interesting environmental things that affect behavior, such as short days and cold temperatures.

I studied psychology and philosophy in college, but I was always interested in the biological basis of behavior. In fact, before I got into immunology, I was a PhD student in clinical psychology — at Fordham University in the Bronx. But I soon discovered that I preferred the more basic science aspects of doing psychology rather than working with people. So I eventually decided to switch fields.

I don’t come from a scientific family. No one in my family even went to college, let alone did science. I think it was all just a kind of a happy accident. I was lucky enough to be exposed to people at the University of Alaska in Anchorage who said, “Hey, you should consider doing graduate school.” That’s how it came about.

What was it like growing up in Alaska?

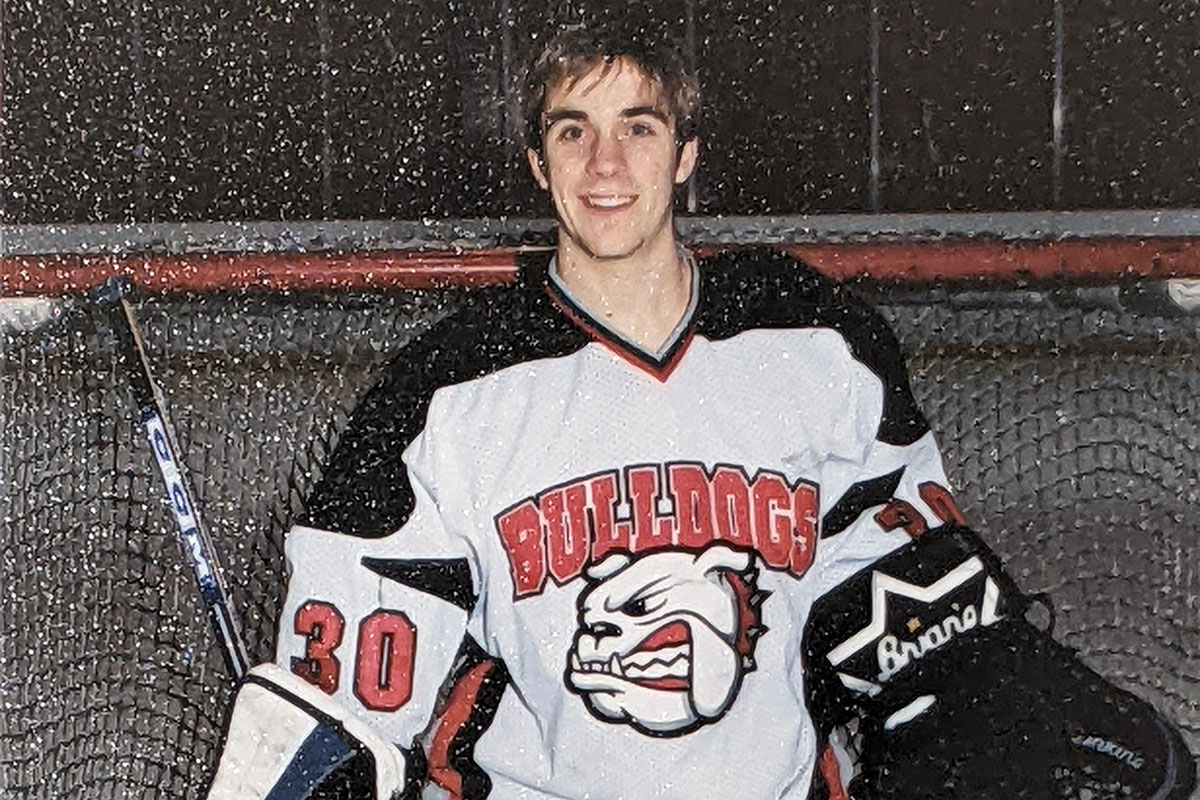

I am a card-carrying Alaskan. I grew up fishing. Was on a boat already as an infant. I went on my first hunting trip at 10. I got my first hunting rifle at 14. I skied, snowboarded, played ice hockey. I camped all the time.

I was raised by my grandparents, who were Alaskan. My grandfather moved to Alaska to work in the insurance business. They lived there for decades before I came around.

Much of my time was spent in a fish camp on the Kenai River in a very rural area. The other part was spent in Anchorage, which is where I went to college.

What was your path to immunology?

A professor of mine in Alaska had a friend in Cincinnati who did neuroimaging research. I knew I wanted to experience places other than Alaska, so I enrolled at the University of Cincinnati and then I did one of those summer undergraduate research fellowships. They were supposed to put me with a traditional neuroscientist, but instead they put me with a neuroimmunologist — someone who studied multiple sclerosis.

When I was graduating, that professor had just moved to the National Institutes of Health, and she said, “Hey, do you want to be a postbaccalaureate fellow at the NIH?” And I was like, “I don’t even know what the NIH is, but sure, let’s do it!” So I moved to DC and spent a couple years working on human immunology and imaging, and discovered I liked that a lot.

Immunology is nice because it underlies everything. The immune system is involved in so many different diseases: cancer, autoimmunity, neurodegeneration — they all have an immune component. Even psychology has an immune component. So that’s what got me into immunology.

Support the essential and compassionate work of our doctors, nurses, researchers, and staff. Your gift will empower MSK to ensure that people with cancer have access to world-class care and research.

How do you explain your research to people who aren’t in your field?

The human body consists of about 30 trillion cells. About 1% of that, or 300 billion cells, die or are shed from the body every day. The vast majority of those have to be cleared — eaten, essentially, by neighboring cells called phagocytes. They have to eat those cells and also break down and get rid of all of that biological material. I like to say that every month you are a new person because of this turnover.

It is the phagocyte’s job to figure out how to manage all of that excess material. And it has to do it really quickly because if it doesn’t and the excess material leaks out, it can lead to things like autoimmunity.

People used to think that autoimmunity was due to a failure of phagocytes to eat and clear up the dying cells. That is true in some cases — lupus and atherosclerosis, for example. But in many cases of autoimmune and chronic inflammatory disease, those macrophages eat just fine.

So we proposed a different idea. What if the issue is not whether or not they eat, but how they eat? We know for humans that nutrition isn’t just a matter of having enough to eat or eating too much; it’s a question of what you eat and how that food is digested. So maybe we need to understand how phagocytes eat, and how they handle the material once they have eaten. This is a completely new way of thinking about it. And we have early evidence to suggest that this may indeed underlie disease.

This line of work is also important for our understanding of cancer development and progression because cancers, especially solid cancers, take advantage of this incredible process. There is substantial evidence that phagocytic clearance of dead cells directly contributes to cancer development and progression. We believe that if we can better understand this area of biology, we will be able to come up with complementary therapeutic approaches for some of the hardest-to-treat cancers, such as triple-negative breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and so on.

What attracted you to the Sloan Kettering Institute?

When my wife and I left New York the first time, we always said that we wanted to move back, — but only if we could afford it and we didn’t have to commute. At the time, I was commuting from Forest Hills, Queens, to the Bronx every day. It was like an hour and a half each way, and I felt like I was losing my soul a bit.

One of my close friends is Mike Overholtzer. I know Mike from the field of cell death research. When I visited New York for a Cancer Research Institute conference, I visited with him and his MSK colleagues Philipp Niethammer and Lydia Finley.

I loved hearing about how MSK really focused on giving you everything you need to do the science you want to do. It didn’t have to be cancer. You could do whatever you were interested in. And they gave you the space, the resources, and the equipment to do this. I knew that if I was fortunate enough to get a job offer from MSK, I was going to come here.

What do you want trainees to know about life in the Perry Lab?

I think if you were to ask members of my lab what they like most about the lab, they’d say the comradery. That’s something I didn’t have in my graduate school lab, but I did have in my postdoc lab. We would meet every day for coffee in the break room and chat science and help each other. I wanted that for my lab, too. So we all go get food or drink together pretty regularly. That sense of comradery is the thing that I hope my trainees take away from the lab, more than anything else.

Do you have a lab motto?

I basically tell my trainees: “Just make a good-faith effort.” When you give a talk or do an experiment, you don’t have to be perfect. You don’t have to be great. Just make an honest attempt.

I think one of the biggest drivers of fraud and academic dishonesty in science is not maliciousness or psychopathy or bad people. I think it’s psychological stress; it’s good people being put in difficult situations. Sometimes we put a lot of pressure on ourselves thinking we need to succeed. We need to get that Cell, Nature, Science paper or whatever. Other times, our advisor puts pressure on us.

But generally speaking, at the end of the day, even if we fail, it’s not the end of the world. If a project doesn’t work out, that’s just the way the science goes. I think that’s really important for trainees to understand.

Most of the interesting things I’ve discovered were not the result of having great thoughts. They’re not things that I could logically derive. Most of the time, what I think initially turns out to be wrong. I get really excited when my hypothesis is wrong, because that means it’s more interesting biology than my brain could imagine.

What’s the most enjoyable or rewarding part of your job?

I love this job because I am fortunate enough to get paid to do what I really, genuinely love to do. I love thinking about science. I could go on a monthlong vacation and not think of or do anything with the lab. I’m allowed to do that, but I don’t want to. I enjoy what I do so much that I’m thinking about it all of the time.

Plus, I get to interact with some of the smartest people in the world, all of whom are smarter than I am. I’m constantly challenged by people who are not just academically but politically and philosophically different than me. I get to be challenged on my beliefs and my worldviews. And I think that’s just such a blessing that not many of my friends who I grew up with get to experience.

What issues are you particularly passionate about?

I believe that the future of science needs to involve families more. I think right now that scientific fields are set up where someone’s career is completely independent of their family life. I would want, as a moral message, to say that that’s wrong. I think my family is an integral part of this, and I want all my trainees to have that same mindset. I don’t want them to think that they have to choose between a science career and having kids.

Another thing I’m passionate about it mentoring kids from back home. I was mentored by a grad student whose mom and dad were scientists at the University of Alaska. He and his wife are now scientists at the University of Alaska. Together, we are working to establish a scholarship for an undergraduate from Alaska to come here for the summer, and we also aim to raise funding for a postbaccalaureate position for college grads. That’s actually a big mission of mine: to give more kids like myself from rural areas opportunities in science. Because I was lucky. Most kids in Alaska don’t even know that places like this exist. They don’t know that opportunities like this exist. So helping them find their way is a pretty important mission to me.