Prostate cancer can be successfully treated with androgen-deprivation therapy (also called hormone therapy), which blocks the cancer-fueling effects of testosterone. Some hormone therapies target the androgen receptor protein on the cancer cells, preventing the testosterone from activating the receptor and stimulating growth.

But these drugs often stop working as the prostate cancer evolves, and researchers and physicians have struggled to find better ways to monitor androgen receptor activity and determine when a tumor is becoming resistant to treatment.

Researchers in the Memorial Sloan Kettering laboratory of Steven Larson may have come a step closer to solving this problem using an antibody that binds to a specific protein, called hK2, which is secreted only by prostate cells — both normal and cancerous. The researchers coupled the antibody, called 11B6, to a radioactive tracing molecule. After binding to hK2, the antibody is taken up by the prostate cells and can be tracked using imaging methods such as PET scans.

They showed that deploying 11B6 made it possible to better track the location of the cancer that has spread to other tissues, as well as determine levels of androgen receptor activity, which could give early warning that a drug is no longer working.

The new method is reported in the journal Science Translational Medicine by MSK molecular pharmacologist Hans David Ulmert and Dr. Larson, along with clinical chemist Hans Lilja and other researchers at MSK and several other institutions.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to target a prostate-specific protein for imaging purposes, which gives us a much clearer signal about response to hormone therapy, as well as the location of cancer in other sites to which it may spread, such as the bones, lymph nodes, or liver,” Dr. Ulmert says.

The antibody 11B6 has already proven to be safe in nonhuman primates, and testing of the imaging antibody in prostate cancer patients could begin as early as next year.

The ‘Ideal’ Protein for Androgen Receptor Monitoring

Focusing on hK2 offers major advantages over previous imaging methods, which were imprecise because the targeted proteins were not exclusive to prostate tissue or tended to wash out of the area over time (because they were not taken back into the prostate cells). Other imaging targets also did not reliably indicate levels of androgen receptor activity and gave researchers no clear sense of whether androgen receptor-suppressive therapies were working.

Dr. Ulmert explains that the presence of the hK2 protein’s expression is directly correlated with activity of the androgen receptor pathway fueled by androgens, making it “the optimal protein to target for this kind of imaging.”

“Having all prostate tissue more clearly imaged also helps surgeons or radiation oncologists be certain they have removed or treated everything necessary,” he says.

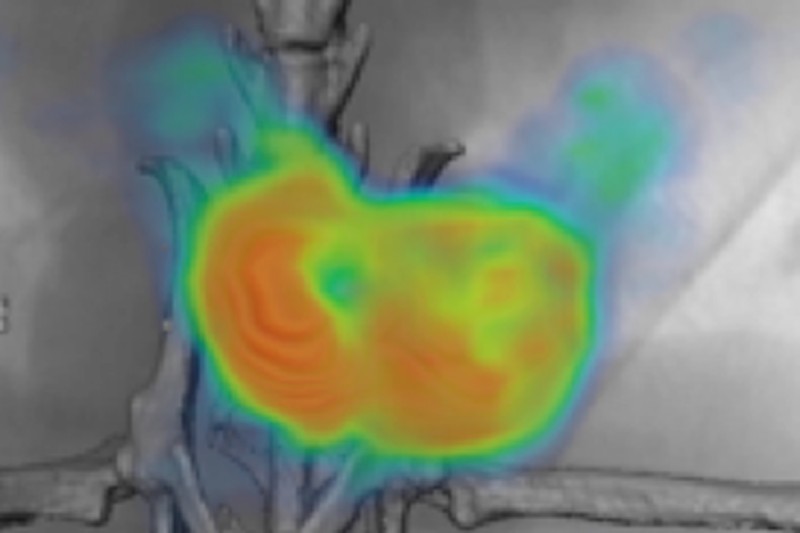

The researchers used 11B6 to accurately detect prostate cancer, including bone metastases in mouse models of the disease, as well as in human tissues. They also demonstrated that this technique could be used to monitor the cancer during treatment.

When given initially to the mice with prostate cancer, the antibody entered the cancer cells and was easily detectable on PET scans. After the mice received androgen receptor-blocking drugs, scans showed that the antibody was taken into the cancer cells at a much lower level, indicating that the antibody’s reduced intake directly correlated with suppressed androgen receptor activity. Researchers also showed the intake increasing again as the tumor grew resistant to the therapy. Presumably, Dr. Ulmert says, this same correlation could hold true in humans with prostate cancer.

Dr. Ulmert also explained that the ability to target secreted proteins has implications well beyond the imaging of prostate cancer. First, it opens the door to imaging a range of other cancers using different antibodies.

In addition, the antibody could potentially be coupled with a toxic agent so that it kills the cancer cells after binding to the secreted protein. Dr. Ulmert and his colleagues in the Larson lab are currently exploring this possibility along with molecular pharmacologist David Scheinberg and radiochemist Michael McDevitt.

“Whether this is done for imaging or drug delivery, it’s very important that we now know there’s a way to reach a target that correlates with disease activity, which is always the goal,” Dr. Ulmert says.