Alicia Kalogeropoulos, with her husband, Alex, joined a clinical trial testing a new drug for her brain tumor. “I am no longer scared because I have faith in the future of medicine and technology,” she says.

Alicia Kalogeropoulos had everything she wanted in her life at age 27: a loving husband, a first house, and a meaningful career as a nurse anesthetist. One day she tripped at home and hit her head. Fearing a concussion, Alicia’s husband, Alex, took her to the emergency room. A scan revealed awful news. She had a tumor in the front of her brain. “I had no symptoms,” she remembers. “It was a complete shock.

Suddenly, Alicia felt her bright future teetering on the edge.

“I was very scared because the only stories I had heard of people with brain tumors didn’t turn out well,” she says.

After a five-hour surgery to remove the tumor, Alicia faced a harrowing decision. Doctors said the cancer was likely to grow again and recommended chemotherapy and radiation. But she worried how these treatments could affect her quality of life, including her fertility.

Then the tumor started to grow.

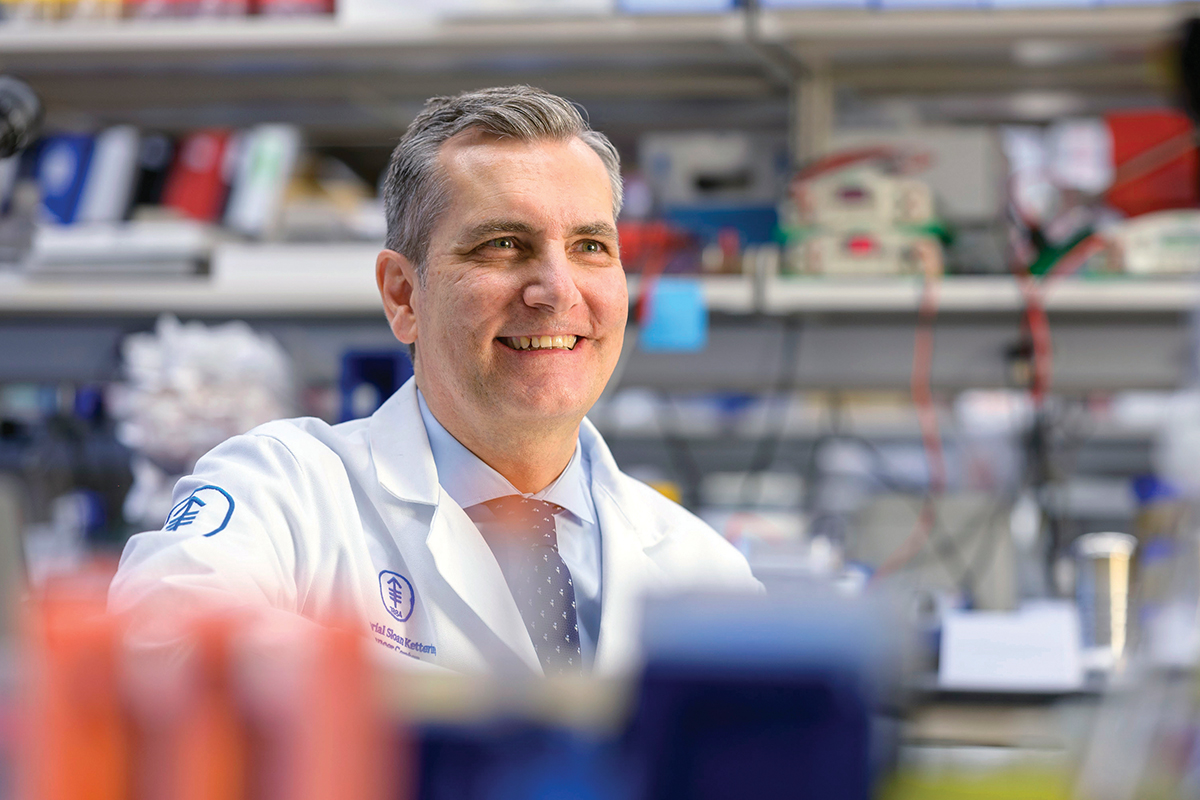

A doctor in Boston told her about another option: A clinical trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) was testing a new drug for her type of cancer, a low-grade glioma — one of the most common. Leading the trial was Ingo Mellinghoff, MD, FACP, Chair of MSK’s Department of Neurology. The drug, vorasidenib, targets a mutation in IDH genes. The mutations are present in 80% of low-grade gliomas, including Alicia’s.

She came to MSK and immediately felt hopeful. “Dr. Mellinghoff and the research nurses were excited and optimistic,” Alicia says. “They made me feel like I was joining a team, not just a trial.”

Results from the phase 3 trial demonstrating vorasidenib’s potential were published in The New England Journal of Medicine and reported by Dr. Mellinghoff at the 2023 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago.

“This has the potential to be the first new treatment option in low-grade gliomas in more than 20 years,” Dr. Mellinghoff says. It happened as a result of years of painstaking work by determined scientists in research labs across MSK.

Why Brain Cancer Is So Hard To Treat

There are more than 125 types of brain cancer, and they are especially challenging to treat. Brain surgery is complex. There is a network of blood vessels and closely spaced cells forming a tight seal to protect against toxins. This blood-brain barrier also makes it difficult for drugs to penetrate. To overcome these hurdles, MSK’s Brain Tumor Center brings together researchers and clinicians across the institution focused on meeting the dire need to improve therapies. Led by Luis Parada, PhD, the team has created a unique resource to study the biology of glioblastomas, the deadliest brain tumors, using models known as patient-derived xenografts (PDX).

Immediately after surgery in the hospital, a patient’s tumor cells are whisked across the street to the laboratory. The human glioblastoma cells grow into a new tumor, which can be analyzed at the molecular level and used to test drugs.

“These PDX models are as close as you can get to experimenting on human brain tumors,” Dr. Parada says. “To my knowledge, no other program is as comprehensive and rigorous as the one we have at MSK.”

Research by Ingo Mellinghoff, MD, FACP, shows a new drug could reach the brain to treat low-grade gliomas.

It’s this kind of collaboration between scientists and clinicians that pushes forward discoveries in the lab into potential treatments for patients.

That’s the story of vorasidenib — now a pill taken once a day. Before the phase 3 clinical trial using it in patients around the world, Dr. Mellinghoff led a phase 1 study, which confirmed that the drug crossed the blood-brain barrier and almost completely blocked the effect of mutant IDH enzymes in tumor cells.

With the phase 3 trial complete, the Food and Drug Administration must still approve vorasidenib before it becomes widely available.

In the wake of this advance against low-grade tumors, MSK researchers hope their PDX models will enable real progress against glioblastomas and other deadly brain tumors.

“There are many exciting drugs in development,” Dr. Mellinghoff says. “We are getting a much better understanding of the genetic changes occurring in these tumors, as well as developing better biomarkers to monitor how the tumors progress or respond to treatment.”

After Alicia started taking vorasidenib in December 2021, her tumor stopped growing. It has held steady and even appeared to shrink slightly in 2023. The drug has caused no side effects.

“I was very scared finding out I had brain cancer initially because I immediately thought this meant I was going to die,” Alicia says. “I am no longer scared because I have faith in the future of medicine and technology.”

This research receives essential philanthropic support from the MSK Giving community, including Cycle for Survival®, Judith W. and Anthony B. Evnin and The AE Family Foundation, Fred’s Team®, Richard A. and Susan P. Friedman, the National Brain Tumor Society, and The Schneider Family (Dr. Mellinghoff); and Cycle for Survival®, Fred’s Team®, the A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation and the Nussdorf Family Foundation, and The Mortimer B. Zuckerman Family Foundation (Dr. Parada).

Dr. Mellinghoff holds the Evnin Family Chair in Neuro-Oncology.

Dr. Parada holds the Albert C. Foster Chair.