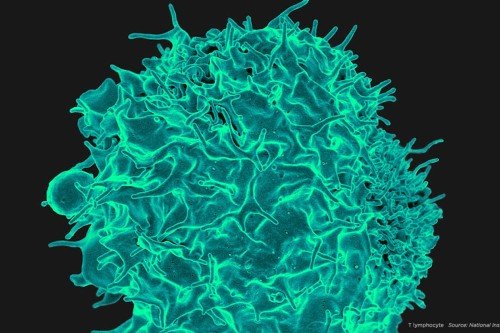

Human CAR T cells have been engineered to produce a protein that could treat lymphoma.

Memorial Sloan Kettering researchers have developed a potentially powerful lymphoma treatment using modified immune cells that function as on-site “micro-pharmacies,” churning out proteins for therapeutic effect. In experiments with human tumors transplanted into mice, the new immunotherapy approach produced significant responses, raising hopes that this technique could someday offer an effective way of treating this disease and possibly other cancers.

The technique represents a new twist on a form of immunotherapy called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy, which has demonstrated remarkable results in patients with other blood-related cancers. CAR T cell therapy involves removing immune T cells from a patient, genetically altering them to fight cancer, and giving them back to the patient in vast numbers.

Historically, this form of therapy has aimed to give immune cells the information they need to better recognize tumor cells as foreign and attack them. The new technique illustrates an untapped potential of CAR T cells to act as targeted delivery vehicles by revamping them to produce anticancer agents.

“This form of treatment could be very effective because the CAR T cells continuously produce the protein right where it is needed,” says MSK cancer biologist Hans-Guido Wendel, who led an international team developing the novel technology that included Karin Tarte of the University of Rennes, France. “It could increase the on-target therapeutic activity and also reduce side effects of cancer treatments because it’s restricted to the tumor sites.”

Disrupted Crosstalk Leads to Lymphoma

The researchers devised the innovative approach after making an important discovery about the biology of lymphomas, which usually arise in white blood cells called B cells and are characterized by uncontrolled growth. The researchers identified a critical pathway that is disrupted in approximately 75 percent of follicular lymphomas, a subset of B cell lymphoma.

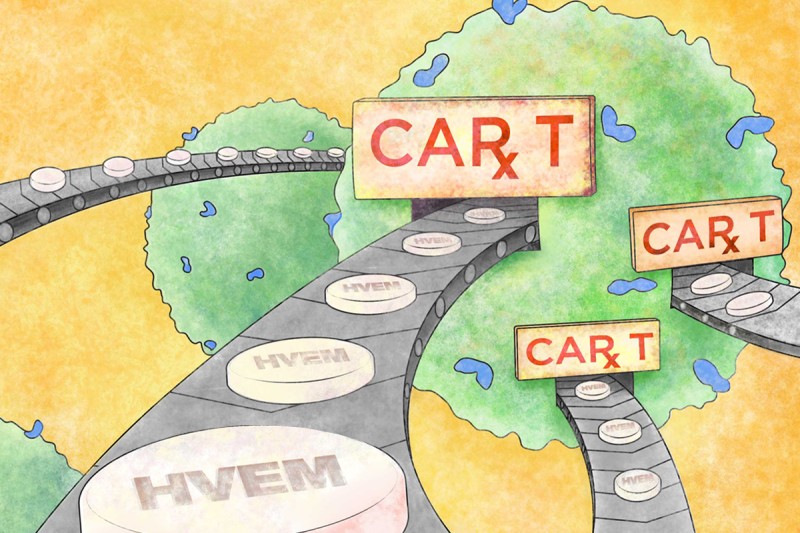

The pathway involves an interaction between two receptors on the surface of B cells, proteins called HVEM and BTLA. Normally, these receptors communicate with each other to keep B cells’ growth at a normal rate. If this communication is disrupted — if either receptor is not functioning properly — the cells will proliferate out of control.

Dr. Wendel and colleagues found that the gene for HVEM is mutated in most follicular lymphomas, producing a faulty HVEM protein that perturbs the interaction with the BTLA receptor that sits on the surface of the cancerous B cells. This accessible location suggested that it might be possible to deliver the HVEM protein therapeutically and restore its cancer-suppressing function.

“The challenge became finding a way to get HVEM to the cancer cells,” Dr. Wendel says. “It’s a big protein that’s very difficult and expensive to manufacture, and if you tried injecting it, you would need a much higher concentration because it binds in a lot of places you don’t want it to. So we decided to see if we could engineer T cells to make the protein instead and also deliver it to the tumor cells.”

CAR T Cells Drawn to the Cancer Site

The research team used human CAR T cells engineered to seek out cells expressing the CD19 protein, which is made by all B cells, both cancerous and normal. CD19 CAR T cells naturally home in on B cells and have recently produced stunning results in treating chemotherapy-resistant leukemia.

The research team modified the CD19 CAR T cells so that they would continuously produce the HVEM protein. “The CAR T cells pump out the protein for several weeks in one specific area — which is near the cancer cells,” Dr. Wendel says.

When injected into mice that contained implanted grafts of human follicular cell lymphoma, the cells produced therapeutic responses that were far more significant than when using control CD19 CAR T cells that did not produce HVEM.

The researchers reported their results online today in the journal Cell.

“This shows a feasible way to put the brakes back on lymphoma cells by restoring the HVEM-BTLA interaction,” Dr. Wendel says.

He adds that additional studies are needed to validate the effectiveness of this approach. Darin Salloum, a postdoctoral research fellow in Dr. Wendel’s lab, is further modifying the CAR T cells to produce altered versions of the HVEM protein in the hopes of making the treatment even more effective. Ultimately, pharmaceutical or biotechnology companies can license the technology to conduct a clinical trial.

“Potentially, engineered T cells that function as ‘micro-pharmacies’ and deliver a range of anticancer drugs could transform the way we treat lymphomas and possibly other blood cancers as well,” Dr. Wendel says.