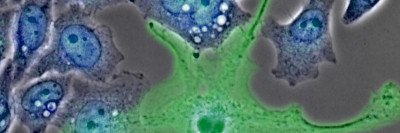

Immune cells called macrophages interact with cancer cells and sometimes fuel their growth and progression.

The interplay between cancer and the immune system is complex. While researchers have recently had striking success stimulating immune cells to destroy tumors — a field of treatment known as immunotherapy — there is also ample evidence that immune cells called macrophages may fuel the growth and progression of cancer.

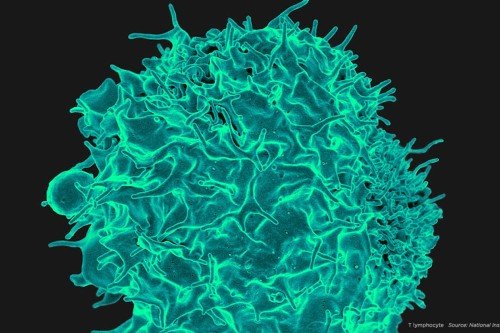

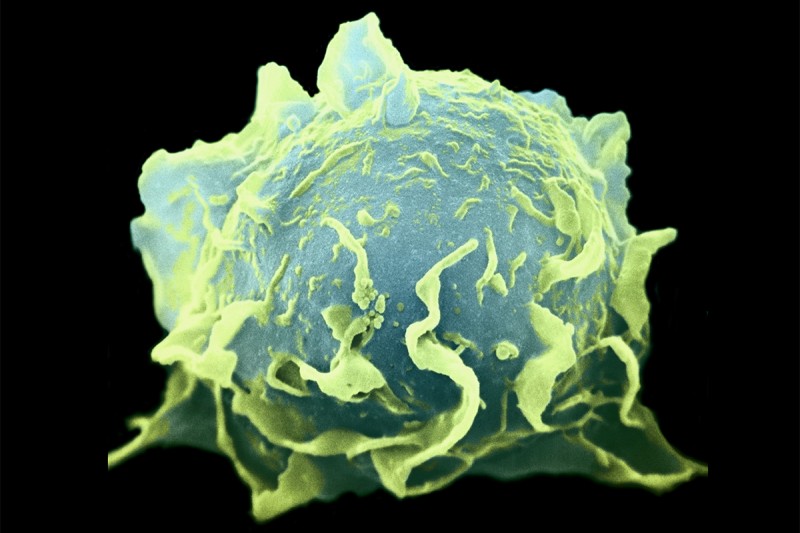

Macrophages (the name means “big eaters”) are large, specialized immune cells that engulf and destroy everything that looks like it doesn’t belong. This process, called phagocytosis, enables organs to function normally. Macrophages are found in virtually all tissues and take on specialized functions in each. Whenever damage, inflammation, or infection occurs, they provide a first-line response to clear away microbes and injured tissue and stimulate cell growth and repair.

Are Macrophages Friend or Foe to Cancers?

Researchers long believed that macrophages found in and around tumors attacked cancer. But in recent years, they began to suspect that macrophages may be more friend than foe to tumors. Cancer cells can hijack macrophages to fuel their own growth or equip themselves to spread to other locations. Because macrophages appear to provide sustenance to cancers, researchers have begun investigating therapies that target them, cutting off the tumor’s support system.

Memorial Sloan Kettering immunologist Frederic Geissmann studies the biology of macrophages and the role they play in cancer. As macrophages consist of a number of subtypes, a major question facing the field is how they specialize, or differentiate, into their diverse types in various tissues. Understanding this process could shed important light on how they come to fight — or to aid — cancer.

“Clarifying how macrophages originate and become specialized is very important to understanding their role in tumor development and progression,” says Elvira Mass, a postdoctoral research fellow in Dr. Geissmann’s lab and the study’s first author. “They are constantly interacting with cancer cells, so the better you understand at a molecular level how they work, the better you may be able to design therapies.”

Dr. Geissmann’s laboratory recently made an important discovery about how and where macrophages develop and differentiate. This insight allows them to better characterize the cellular and molecular identities of macrophage subtypes and could shift the strategy of some cancer therapies.

Rewriting the Textbooks

Macrophages are actually a subtype of a larger group of immune cells called phagocytes. For decades, scientists have thought that macrophages arise from predecessor phagocyte cells in the bone marrow called monocytes. The standard view has been that monocytes circulate in the blood and then leave the blood vessels to differentiate into different macrophage types based on where they end up in the body.

Now Dr. Geissmann and colleagues have discovered that most macrophages that reside in the tissues are present there from a very early embryonic stage. The finding is reported this week in the journal Science.

“This is a completely different model from what has been understood for the past century, and what is currently in textbooks,” he says.

These tissue-resident macrophages are formed along with the tissues from the mesoderm — the middle layer of the embryo — rather than from bone marrow monocytes. The researchers found that very early in development, precursor cells called pMacs spread throughout the embryo to differentiate into tissue-specific macrophages. This appears to be guided by signals they receive from the surrounding cells in the various tissues.

“It’s not clear what roles these tissue-resident macrophages are playing at that early stage,” Dr. Geissmann says. “They may be there to help protect against infections that the mother acquires during pregnancy. But they also could be an integral part of organ formation, pruning away cells that need to be removed in order for an organ to be sculpted into its proper shape.”

Two-Tiered System

The researchers made their discovery by combining several technologies to “map” the location of the macrophages in mouse embryos as the cells progressed from the pMac stage to the fully developed, tissue-specific stage.

The researchers propose a new, layered model for the organization and function of phagocytes: Macrophages reside in the tissues and are distinct from monocytes that develop in the bone marrow, circulate throughout the body, and can home in on signs of trouble such as infection.

This discovery is important in the context of cancer and other diseases, Dr. Geismann explains, because different types of phagocytes might have different impacts on tumor initiation, growth, and metastasis. “A clear picture of macrophage development will be critical for researchers to design and use novel molecules for therapeutic purpose,” he says.