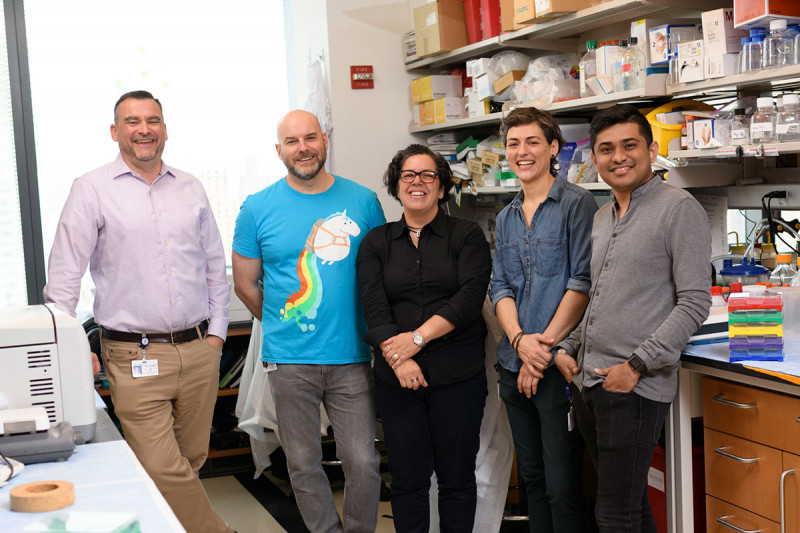

They’re here. They’re queer. They’re scientists.

In honor of Pride month, we wanted to explore what it’s like to be both a scientist and a person who identifies as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer.

Does being LGBTQ present unique challenges to one’s career as a scientist? Is it harder or easier to be out in science than in other fields? What difference — if any — does being queer make to a scientific life?

To find out, we spoke to five scientists at Memorial Sloan Kettering, each of whom has had very different, and illuminating, experiences.

Scott Keeney

I came out as gay my senior year of college, at Virginia Tech. I graduated in 1987 and then I went to the University of California, Berkeley for grad school. Part of the reason why I picked the Bay Area, and Berkeley in particular, was because I had figured myself out to that degree and that was an obvious place to go.

This was at the height of the AIDS epidemic and the very early days of ACT UP and other activism around AIDS. Compared to lots of places, Berkeley was pretty enlightened. But being gay was not something many straight people were personally familiar with or understood at the time, and almost all of the scientists I knew were straight.

When I interviewed for a job at MSK in 1997, one of the very first things my interviewer — Ken Marians, then the Molecular Biology Program Chair — and I talked about was the fact that MSK didn’t have domestic partner benefits. He said that it had been discussed among the leadership and that he believed it would eventually happen, but he couldn’t guarantee when.

A few years later, Harold Varmus held a town hall for faculty soon after he became president [of MSK]. He opened the floor up to questions and I asked, “Are there going to be domestic partner benefits?” My recollection of what happened is that he turned to [then VP of SKI administration] Linda Stevenson, who was sitting next to him, with a very surprised look on his face, to the effect of, We don’t already have domestic partner benefits? How is that possible? He said, “We’ll get on that.” And shortly thereafter, we had domestic partner benefits. I’d like to take credit for being the pebble that started the landslide.

I think for someone just coming to terms with their sexuality, it’s easier now in some ways. There’s been a sea change in acceptance. Especially among the younger generation, the attitudes toward it seem to be much more matter of fact. But I think it’s every bit as difficult on a personal level because heterosexuality is still the default; cisgender is still the default. Learning that everything you’ve been socialized to be is not actually who you are is disruptive to you and to your loved ones. It’s potentially traumatic. I don’t think that’s any different now than it was before.

I think visibility is important. You never learn about most of the times when being out has helped somebody else feel more comfortable. But I’ve gotten feedback from time to time that has made me understand how important this is.

Just this past week, in fact, I received an email from a student, an undergraduate, who found me on Twitter and wanted to thank me for being an example of someone who was out in his field. It really means a lot to me to know that I have helped someone in this way.

Read more of Scott Keeney’s story at 500queerscientists.com

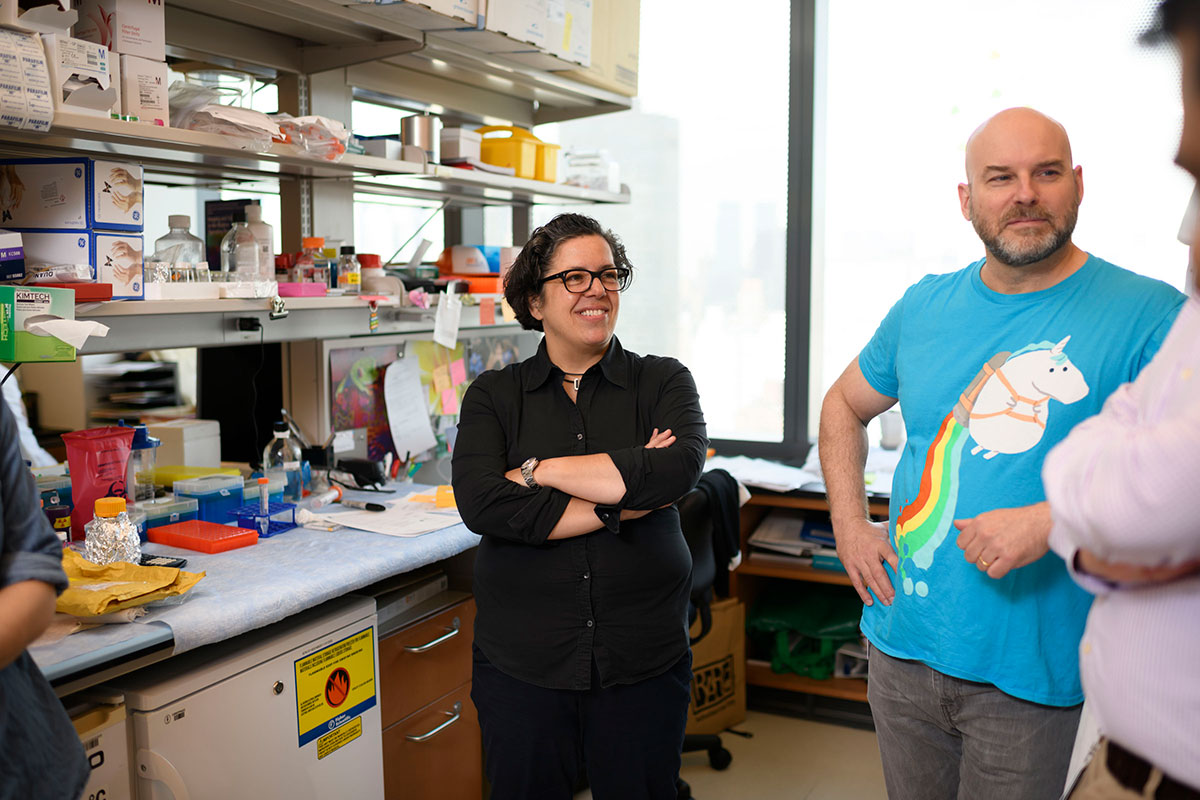

Kat Hadjantonakis

I really don’t like labels, other than that of scientist. I don’t like to be pigeonholed. Especially in an age of increased diversity and inclusivity, and when gender categories are blurring, I don’t feel a need to claim a particular identity.

I’ve never made announcements about my sexual orientation at work, but people eventually find out. I’m probably not as forthcoming in my professional capacity as some. It may have something to do with being British, and also maybe being female. Female faculty are not only underrepresented, I think generally speaking they’re not as forthcoming or maybe not as confident about many things, including revealing personal details.

There’s also the matter of where one is in one’s career. As I’ve become more senior, it hasn’t concerned me much whether people know about my sexual orientation or not. Whereas I think when you’re more junior you might be a little bit more cautious about revealing too much.

The first primary investigator that I worked with as a postdoc [in Canada] used to make inappropriate jokes that I and many others in the lab at the time found highly offensive. They were homophobic, sexist, and everything else. It was a difficult environment to work in. A number of us complained but nothing was done, and as a consequence I actually left that lab. I think attitudes are improving, but I feel they have some way to go.

I did my undergraduate degree and PhD at Imperial College in London, so I was used to the diversity of big cities. I interviewed for postdoc fellowships in a number of cities in the United States, including some smaller cities in the Midwest and South. This was 25 years ago. It was very clear from those interview visits that going there would be a bit of culture shock and it really wasn’t going to work out for me there personally, even if the professional environment was exceptional. Brigid Hogan, who just retired as Chair of the Department of Cell Biology at Duke, and I still joke about how as soon as I got off the plane it was evidently clear that I would likely not end up coming to her lab in Nashville for my postdoc, when she was on the faculty at Vanderbilt. I’ve been back there since and things have changed, as certainly I have.

I’ve been invited to speak on several panels about LGBTQ individuals in science. My message is always that it’s the science that matters most. We are in a professional environment after all! You shouldn’t be concerned about being judged for other reasons, but if you feel you are, then you should take action. I would like to think that in this day and age, one would expect not to be judged on anything else. And I believe that this is the case at MSK.

Suleman Hussain

I’m out to everybody here at MSK, including my boss and lab mates. This is different from when I was doing my PhD in Texas. I was out to only some of my lab mates there, who were very supportive.

It’s been a long process. The first step was coming out to myself. I lived in India then so it was a completely different ball game. Homosexuality is still criminalized in India, and the gay community is very underground. I was fortunate to meet the man who would become my husband in Mumbai in 2011. After years of a long-distance relationship, he joined me in Texas and we tied the knot soon after same-sex marriages were legalized in the state.

When I came to MSK in 2016, I made the decision that I was going to be out. Being married makes it a bit easier. It’s kind of a conversation topic. I refer to my husband and then everyone just knows.

My family still doesn’t know that I’m gay or that I’m married. I grew up Muslim so it’s a little more difficult to be open about homosexuality in that religious context. But I have grown more comfortable and more confident in myself. At this point, if they somehow find out then I’m ready for it.

I feel very privileged. I’ve been able to live the life I truly wanted.

The reason why visibility of LGBTQ people in science is so important is because we serve as examples to gay teens, who go through a lot. For them to be inspired to do what they are really capable of, that’s what motivates me to be visible. It’s become much easier now overall than what it was before, but still there are a lot of homeless LGBTQ teens and higher rates of suicide too. So in that sense it’s very important for them to have examples.

I’m a board member of the South Asian LGBT Association (SALGA) in New York. We strive to build a strong community and support each other. Especially for people with our cultural background, it’s important to find these welcoming places.

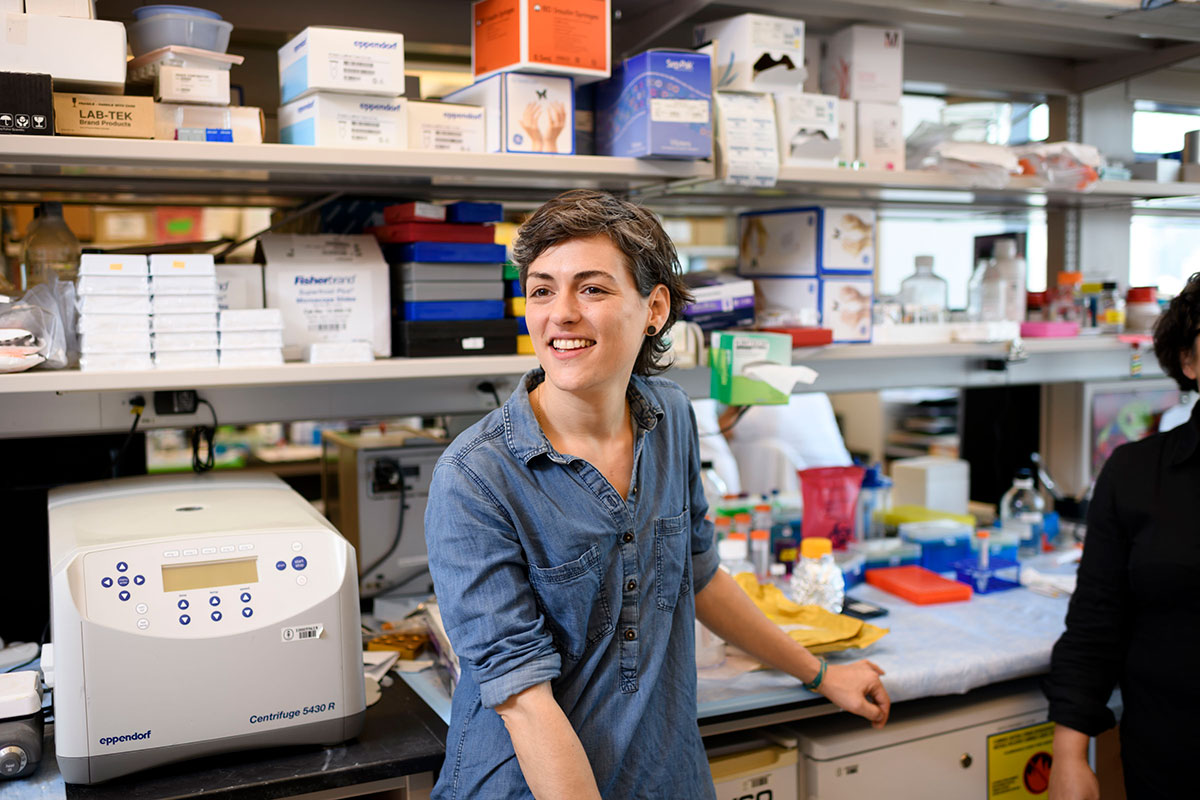

Stefanie Windner

Overall, I’ve had a really good experience as a queer woman at MSK. But I also chose my lab based in part on people I knew I wanted to work with. I needed to have a welcoming and accepting environment. Science is hard enough without needing to fight for one’s daily representation.

It was also really important to me that I was not the only queer person around. We’re in New York City, so obviously it’s a pretty diverse place already, but also MSK does a good job of fostering diversity.

Being a queer person in science can be really isolating. If you’re a white, heteronormative person in science, you can find many people like you. If you’re a queer person — especially if you’re transgender, or nonbinary, or a person with intersecting identities such as a queer person of color — you’re alone for most of your days. It can be difficult to find communities to hold onto.

LGBTQ people are more visible now across the board, but it’s definitely still necessary to promote visibility in science. Many young queer scientists give up because they don’t feel there is a place for them. That’s a real problem. It doesn’t have to be direct violence or rejection. If you go to work and you’re misgendered every day, that can be painful, frustrating, and discouraging. Your love for science can be strong, but that’s not necessarily enough to keep you going.

It’s always important to find people that you can identify with who are further along in your chosen career. This is my first job working with a female principal investigator and my first department with an out and proud queer, female PI, Kat Hadjantonakis, whose lab is next to ours. I’m glad to have found people I can identify with on that level.

I used to identify more as a woman in science. Now I think of myself more as a queer woman in science. I mean obviously I’m both, and depending on the context, one is more important than the other. But I’m trying to emphasize the queer point more nowadays. There are so few of us here so I feel it needs emphasizing. In a way, that’s an argument for becoming a PI myself. It’s scary because it means a lot of responsibility in creating space for future queer scientists, but someone has to help break the queer glass ceiling.

Jason Lewis

Fortunately, being gay in science has never really been an issue for me. I hardly even think about it. I’ve had a husband for over 20 years, but my sexual orientation is not something that defines me. I’m a scientist, partner, and father first. Everything else is secondary.

One thing that I do feel strongly about is institutional support for LGBTQ families. My husband and I have two young children, two-year-old twins. It was a bit challenging at first because my husband also works at MSK — he’s a nurse. And federal policy is that if both parents work at the same institution, you have to share the medical leave benefits. My husband, Mikel, ended up using our whole 12-week benefit share and I kept working. And since the children were born more than five weeks premature, that time went very quickly. It changed this year; now New York State and MSK have paid family leave for both parents.

MSK was very supportive when we decided to have kids. They already had an adoption benefit that they offer to families. When we asked, they agreed to apply it to our surrogacy too. So MSK helped pay some of our legal fees. I think MSK realizes that things need to change sometimes. They’ve been very adaptable to changing needs.

Being out in science may be easier than in some fields. I say that because scientists are supposed to be more objective. Like, what difference does it make? It’s about the quality of the science, not the person’s identity.

I remember I was giving a presentation once, and in the last slide I shared a picture of Mikel and the kids. I said, “I couldn’t have done this without the understanding of my husband, who for years has put up with my travel.” I didn’t have any qualms about sharing that. A couple of people come up to me afterwards and said, “Wow, that was really amazing.” And I thought to myself, Why? If I had a wife and two kids I would say the same thing. I’ve never really understood at the time why it should be any different.

If there is anybody, a trainee or a student, who’s struggling in some way with this, struggling with acceptance, there are lots and lots of people that they can talk to at MSK. There are many amazing resources available to them. They should know they aren’t the only one and there’s always somebody they can talk to. My door is always open.