9:54 AM: It’s an unusual Tuesday in Bill Tap’s sarcoma clinic. He’s been reviewing his patient list, along with notes on each person, for the better part of the morning. The schedule, 17 people, is a light day for him. “This is quiet,” he says. “I’d usually have double this amount.”

Indeed, more than 100 people with a variety of sarcomas are seen at the clinic at Memorial Sloan Kettering’s Rockefeller Outpatient Pavilion on 53rd Street on an average day. Sarcoma, a potentially deadly group of cancers, accounts for just about 1% of all cancers. As a result, it isn’t widely known, and many doctors have never diagnosed or treated it. Unlike tumors that occur in a particular organ (the prostate or lung, for example), sarcomas can appear almost anywhere in the body. There are more than 50 different types of sarcoma, all wholly unique.

This level of complexity, of both the disease and its treatment, is what brings so many people to Dr. Tap and his colleagues. “MSK offers people with sarcoma a depth of experience that few other hospitals in the world can match,” he says. “This expertise extends across all age groups, from sarcomas that affect babies and young children to those that are primarily found in older adults.”

Learn more >

10:25 AM: Medical oncologist Sandra D’Angelo drops in to ask Dr. Tap about a patient who has taken part in a study of pembrolizumab (Keytruda®), an immunotherapy treatment.

Pembrolizumab is a checkpoint inhibitor, a class of drugs that take the brakes off the immune system and allow it to target cancer. Originally used to treat melanoma, these drugs are showing promising results for a number of different cancers, including many types of sarcoma. Doctors and researchers at MSK are leading the way in developing and testing immunotherapy treatments for sarcomas.

Drs. Tap and D’Angelo discuss treatment options for the patient and decide to have her seen by a colleague in radiation oncology. Radiation therapy, given before or after surgery, is part of the standard treatment for many types of sarcoma, and is also commonly used for people who have metastatic disease to complement other therapies. It may boost the effectiveness of checkpoint inhibitors by making tumor cells more visible to the immune system.

Getting the Right Diagnosis

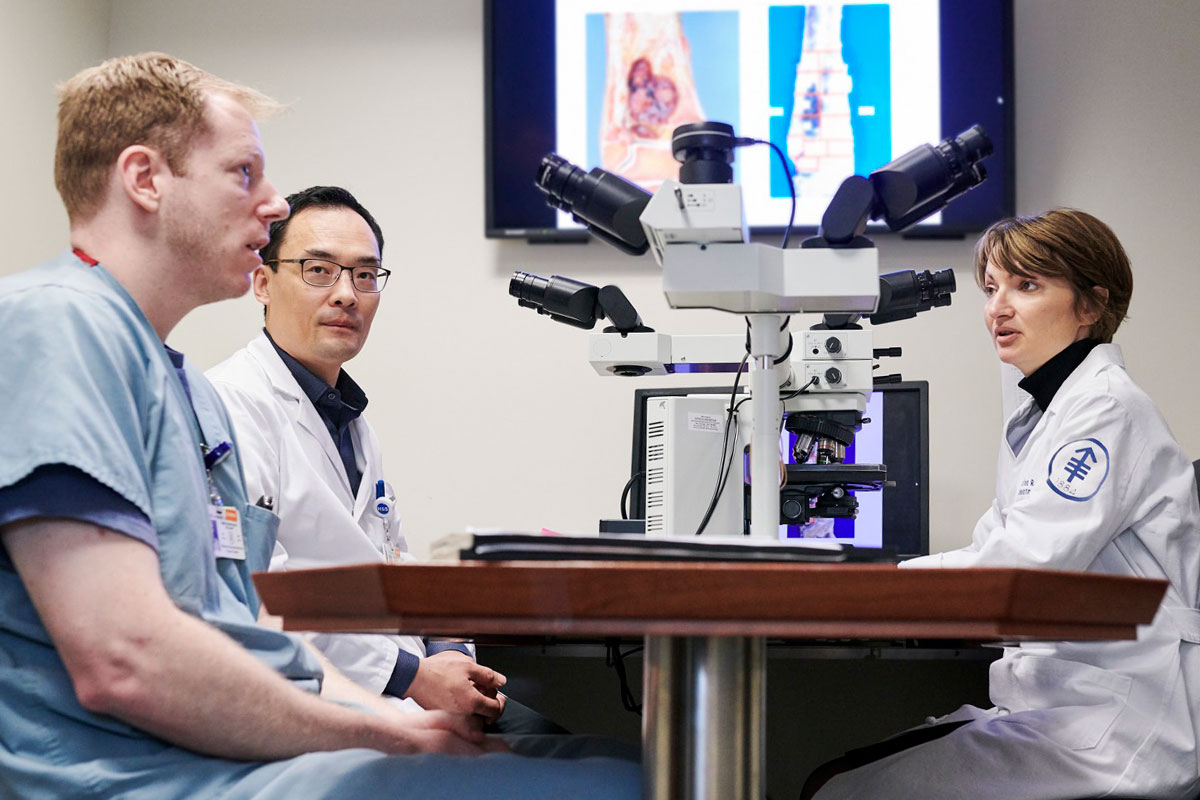

10:35 AM: High school student Clare Nimura is shadowing Dr. Tap this morning as part of a program the sarcoma team has created for budding medical professionals. To give Ms. Nimura the full picture of the disease, Dr. Tap suggests she visit the lab of pathologist Cristina Antonescu, who has specialized in diagnosing sarcomas for more than 20 years at MSK.

“Many different types of sarcoma can look similar under a microscope,” says Dr. Tap. “Molecular pathology is important not just for categorizing each tumor but also for learning about the molecular changes that drive it and eventually find ways to stop that growth. It can even change a diagnosis entirely.”

“When samples are sent to us from other hospitals for a second opinion, I would estimate that we change the diagnosis 10 to 15% of the time,” says Dr. Antonescu. “This can have big implications. Because some of these tumors are so rare, many pathologists don’t have the necessary experience to identify the nuances. But you have to know what’s driving a tumor to identify the best treatment.”

She and investigator Marc Ladanyi, Chief of the Molecular Diagnostics Service, have focused their careers on sarcoma and have discovered many of the genetic changes that drive its formation and spread.

11:15 AM: Jason Chan, one of Dr. Tap’s two medical oncology fellows, pokes his head in the doorway. (Dr. Tap has a general open-door policy.) He’s just met with a patient and wants to give Dr. Tap the rundown. The person is considering leaving her primary oncologist, near her home, and coming to MSK.

The woman has been diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), a rare cancer that develops in the digestive tract. Dr. Tap’s visit with the family lasts nearly 30 minutes. He explains that MSK’s extensive expertise offers the best hope for a positive outcome, but also suggests he can coordinate care with her local oncologist. “What she really needs is to be treated here on a clinical trial,” he says after he leaves her consultation room. But all he can offer today is guidance.

“Whenever I meet a prospective patient for the first time,” Dr. Tap says, “they set the tone. Are they anxious? Upset? Lost? Then my job is to decide what is the best role we can play to help this person and their family. That’s the key.”

Though GIST is uncommon, it can be treated with targeted therapies, including imatinib (Gleevec®). MSK investigators led much of the work that resulted in the US Food and Drug Administration’s approval of imatinib for GIST in 2002. Dr. Tap led the development of another targeted sarcoma drug, olaratumab (Lartruvo), which the FDA approved in 2016.

(Editor’s note: On April 25, 2019, Eli Lilly, the company that makes olaratumab (Lartruvo®), announced that it was withdrawing the drug from the market. This move came after results from a phase III clinical trial found the drug did not improve survival for people with soft tissue sarcoma. The company said it was establishing a program that would allow people who have benefited from the drug to continue to have access to it.)

Offering a Surgical Solution

12:17 PM: Back in his office, Dr. Tap is greeted by surgeon-scientist Samuel Singer, with whom he collaborates on a daily basis. Dr. Singer arrives with two surgical fellows to talk through a patient’s treatment options.

Surgery is the primary treatment for many soft tissue sarcomas. For people with early-stage, less-aggressive cancers, surgery may be the only treatment they need. “We do about 650 sarcoma surgeries a year at MSK, and many of our surgeons have dedicated their entire practice to sarcoma,” Dr. Singer says. “They have the know-how to do operations that have the best chance of removing all the cancer while at the same time preserving as much function as possible.”

MSK surgeons have developed a number of specialized approaches for removing sarcomas. These include laparoscopic or robotic surgeries so people can recover faster and limb-sparing procedures for tumors in the arms and legs. MSK’s plastic and reconstructive surgeons help people regain both their appearance and function after the tumor is removed.

For many people, though, surgery alone is not enough. Sarcomas may come back afterward and may spread to other parts of the body, including vital organs like the liver and lungs. Or their location in the body may make surgery too difficult. This is where Dr. Tap and his colleagues in medical oncology and radiation oncology come in, looking for other ways to eliminate these tumors.

12:44 PM: Dr. Tap walks past a platter of pastries on a desk in the hallway on the way back from another patient visit and offers them to anyone around. He chooses one, takes a bite, and makes a face. “I hoped this was blueberry,” he says. “It isn’t.” He eats it anyway.

Understanding the Biology of Sarcoma

2:14 PM: Dr. Tap takes a moment in between patient visits to check his email. He’s gotten some notes that relate to ongoing sarcoma research in labs at MSK. This kind of research is vital to increasing the understanding of sarcoma.

Most sarcomas begin in tissues that form the mesoderm, the part of a developing embryo that creates the body’s supportive structures. By contrast, the majority of common cancers arise from tissues that begin in the ectoderm (like skin, breast, lung, and colon cancers) or in organs that develop from the endoderm (like liver, pancreatic, and thyroid cancers).

This makes understanding developmental biology, the study of how embryos develop from a single fertilized egg into all of the tissues in the body, an important focus of sarcoma research. “We tap into areas of basic science as well as clinical research and drug development,” Dr. Tap explains. “By understanding at the molecular level how these cells and tissues develop normally, as well as how they transform into cancer, we can create better treatments.”

One major resource Dr. Tap and others use is a database of more than 10,000 people treated for sarcoma at MSK. It was started more than 20 years ago by pioneering sarcoma surgeon Murray Brennan and includes clinical records and medical histories, images of pathology samples, and, now, details about the genetic and other molecular changes driving tumor growth.

“This database helps us understand the clinical nuances of the disease, so we can then begin to figure out which treatments may benefit which patients,” Dr. Singer explains. “It also helps us to identify areas for new research.”

One such area of focus is on pediatric sarcomas. Although they are very rare, sarcomas are relatively more common in children than they are in adults, making up about 15 percent of all childhood cancers. MSK’s Pediatric Translational Medicine Program is focused on translating discoveries made in the lab into the clinic for sarcomas as well as other pediatric cancers.

A Global Team Effort

2:44 PM: Dr. Tap emerges from a consultation room along with Reema Patel, a clinical observer who is beginning a sarcoma program at the University of Kentucky. Dr. Patel is working with Dr. Tap for a month to learn about how MSK operates so she can take those lessons back to her patients. Throughout the course of the year, Dr. Tap says, doctors from Europe, South America, Asia, and across the United States visit MSK’s sarcoma clinic.

“Because of the nature of the disease, it’s a really small international community of people who treat it,” he adds. “Fostering relationships between other experts is vital to advancing progress and caring for as many people as possible.”

MSK treats more people with sarcoma than most other places in the world, including about 70% of those with the disease who live in the New York City area. But not everyone wants to or can come to MSK for treatment. Thus many efforts are focused on setting the standards for care and sharing the findings made in MSK’s labs and clinics widely.

The team gets emails from people across the United States and around the world asking for advice and gauging whether patients should travel to MSK for treatment. “Your first thought is to say, yeah, of course, come here,” he adds. “We try to fit everyone in. But you have to be wise about the decision and do what you think is really best for the patient.”

Care with a Personal Touch

3:00 PM: A long-time patient of Dr. Tap’s injects some levity into the day, joking with the team and ribbing Dr. Tap about his baby face. (He’s a youthful 47.) When developing relationships with patients, “there are two things you need to do,” Dr. Tap says. “You have to really pay attention to people and pick out the subtle things, both physically and mentally, that the disease is doing to them — affecting their mood or their outlook. Then it’s the conversations, the nuances. You enter medicine and you learn how to interact with people to the best of your ability, and also how not to interact.”

With a disease like sarcoma, doctors must also learn how to give potentially devastating information. “Giving bad news is not easy,” he adds. “If you have frustration, it can transfer to the patient. At the same time, if you bring in a lot of hope and it’s not warranted, that’s not always the best thing either.”

This particular interaction was a happy one. After this, there are several more people to see, more rounds of support to provide, options to offer, and advice to give. But Dr. Tap’s kind bedside manner never wavers. And this was a light day.