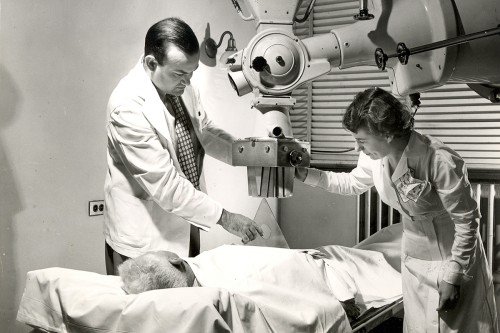

The total body irradiation ward, or Heublein unit, at Memorial Hospital, circa 1931. (Note birdcage with canary.) Credit: Radiologic Society of North America

In the wake of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, public health officials feared the prospect of a radioactive “dirty” bomb going off in an American city. In addition to inciting mass hysteria, this form of terrorism would hobble a medical system ill equipped to deal with radiation injuries, or even to test for radiation exposure.

Beginning in 2003, with support from the Department of Homeland Security and the National Institutes of Health, a team of researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering and Columbia University collaborated on a project to solve some of these problems by developing a way to test people for radiation exposure. The idea was to draw a dotted line between specific levels of radiation exposure and changes in gene expression in blood cells.

There was just one problem: “The Columbia team had developed a system to do gene expression profiling of blood cells, but they didn’t have any human patients — people who were exposed to total body radiation — in order to validate the test,” says Christopher Barker, a radiation oncologist at MSK who helped come up with a solution.

Dr. Barker knew that patients undergoing a bone marrow transplant are often treated with total body irradiation before beginning the transplant to kill the diseased marrow. Working with MSK’s transplant team, Dr. Barker led a study of patients who were undergoing total body irradiation as part of their treatment. With the patients’ consent, the team took a little bit of extra blood before, during, and after the radiation. The blood was then analyzed with the Columbia team’s blood test.

A New Question

The team published their results in 2011, which showed that the test worked beautifully. But that wasn’t the end of the story for Dr. Barker.

“As we were working on this project, I became interested in where the idea of total body irradiation came from originally — really digging down to where it all began,” Dr. Barker says. “I was surprised to find out that some of the initial experiences with this technique, at least in North America, were here at MSK.”

With the help of MSK’s medical librarian and archivist, he was able to piece together the largely forgotten history of an unusual cancer treatment.

The Heublein Unit

By the 1920s, it was clear to scientists that cancerous and normal tissues have different sensitivities to radiation, which led to efforts to tailor radiation treatments. A single large dose of radiation could indeed cause cancers to regress, but it also killed healthy tissues. Splitting up the dose of radiation into smaller “fractions” administered over several days could kill a tumor while sparing normal tissues. (We now know this is because normal cells are more able to repair DNA damage than cancer cells; the technique of splitting doses is called fractionation.)

It wasn’t long before doctors began experimenting with low doses of radiation as a systemic, or body-wide, therapy for cancers that had spread or were in the blood. The idea was to kill cancer cells dispersed in the body without seriously harming the patient.

In 1931, Arthur Heublein, a radiologist from Hartford, Connecticut, and Gioacchino Failla, a physicist at Memorial Hospital, developed the first total body irradiation (TBI) ward in North America, housed at Memorial Hospital. Known as the Heublein unit, this lead-walled radiation room had an x-ray machine located at one end that could be kept running continuously. The room was designed to treat four patients simultaneously with low-level x-rays for about 20 hours a day for one to two weeks.

A canary in a birdcage was placed inside the room — “to give an indication of the possible harmful effects of prolonged irradiation,” Dr. Heublein wrote.

Between 1931 and 1940, approximately 270 cancer patients were treated with TBI at Memorial. The researchers found that the technique was more effective at treating patients with blood cancers like leukemia and lymphoma than those with carcinomas or sarcomas, for whom it was ineffective.

Additional experience — both from laboratory experiments and human radiation exposures — confirmed that radiation was an effective way to kill cells in the bone marrow. (The rapid division of these cells makes them more vulnerable.) As a result, TBI was eventually recognized as a valuable way to prepare a patient for the then-new technique of bone marrow transplant.

It was in this context that TBI would have its biggest impact in medicine, offering the first curative treatment for blood cancers. The first reported use of TBI in conjunction with a bone marrow transplant was in 1957 at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center. The first complete cure of a leukemia patient using this approach occurred in 1969. The technique is still used today.

Wartime Concerns

Doctors weren’t the only ones interested in TBI at mid-century. In the early 1940s, the US Department of Defense (DOD) sponsored research into TBI as part of the Manhattan Project — the government’s secret project to build an atomic bomb. The DOD was interested in understanding the effects of acute radiation exposure and in developing tests that would quantify this exposure, with the ultimate goal of protecting military personnel involved in handling radioactivity and those exposed to atomic weapons.

From the 1940s through the late 1960s, the DOD sponsored research studies in patients with advanced cancers at several US hospitals — among them MD Anderson, Baylor University College of Medicine, the US Naval Hospital, and MSK. The DOD hoped that this research into cancer would provide lessons applicable to soldiers.

Some of this research was ethically dubious. At the University of Cincinnati, for example, patients with advanced metastatic cancers were treated with TBI in the absence of any clear anticipated benefit and without informing them that they were part of medical research. A report written in 1995 by the US Department of Energy’s Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments brought attention to this research and criticized the ethical lapses.

The political fallout from this episode may have contributed to people’s negative views of radiation and its perceived dangers, Dr. Barker says.

Immune System Link

Despite its tangled history, TBI continues to be a very effective cancer treatment when used as part of a bone marrow transplant. In fact, as Dr. Barker points out, by permitting the development of bone marrow transplantation, TBI played an important role in facilitating what is in essence the first immunotherapy for cancer.

Dr. Barker thinks there may be other cases in which radiation may synergize with immunotherapy. “There are clearly examples, at least in laboratory models, where we see no effect of the immunotherapy by itself,” he says. “And when you add radiation, the outcome completely changes, and the immunotherapy becomes more effective. That to us is very exciting.”

There are also cases in which a patient receives radiation to a tumor at one location in the body that is not responding to immunotherapy and tumors elsewhere disappear as a result. Dr. Barker published a paper on this finding, called the abscopal effect, in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2012.

He is currently collaborating with his MSK colleagues Michael Postow and Jedd Wolchok on clinical trials combining immunotherapy and radiation therapy in patients with melanoma (16-380, 16-224).

Dr. Barker has presented his historical findings on TBI at the American Society for Radiation Oncology annual meeting and written several book chapters on the history and present-day use of total body irradiation.