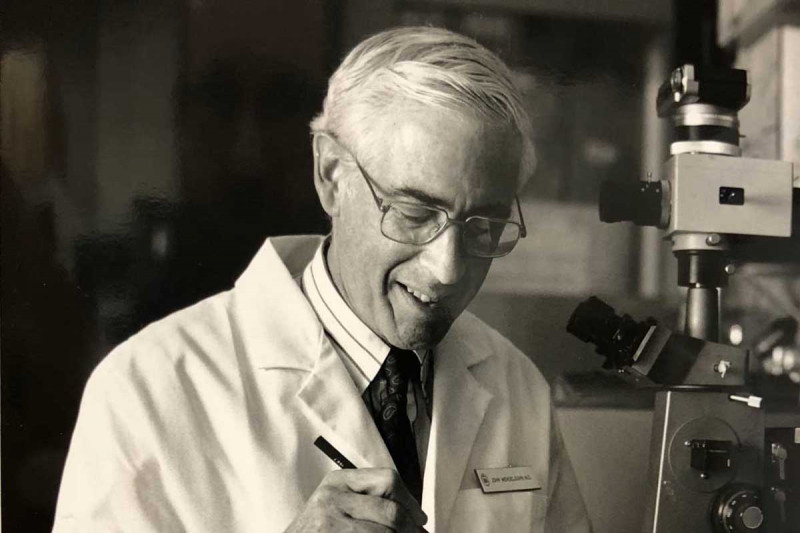

If you are one of the millions of people who have benefited from a targeted cancer therapy, such as trastuzumab (Herceptin®) or cetuximab (Erbitux®), you can thank John Mendelsohn, the physician-scientist who pioneered this approach.

Dr. Mendelsohn died this week at the age of 82 from glioblastoma, a type of aggressive brain cancer. At the time of his death, he was President Emeritus of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. But he had strong ties to Memorial Sloan Kettering too.

Dr. Mendelsohn led MSK’s Department of Medicine from 1985 to 1996. He also co-chaired the Molecular Pharmacology Program in the Sloan Kettering Institute from 1985 to 1990. In both positions, he helped translate basic scientific discoveries about cancer cells into powerful therapies for people with cancer.

Perhaps his greatest scientific contribution was to the field that we now call precision medicine.

Taking a Cue from Nature

It all began back in the 1980s at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), where Dr. Mendelsohn was establishing a cancer center. There, he and fellow UCSD biologist Gordon Sato proposed a provocative new idea: to use an antibody to block a protein called epidermal growth factor (EGF) from binding to its receptor on the outside of cells.

EGF was known to be a necessary growth signal for all cells. In the mid-1980s, scientists discovered that many cancers had elevated levels of the receptor for EGF. This suggested that these cells had a greater dependence on this growth signal. Dr. Mendelsohn reasoned that cancer cells would be more sensitive than normal cells to deprivation of EGF.

He was inspired by examples of this phenomenon happening naturally. In the autoimmune disorder called myasthenia gravis, for example, an antibody blocks the signal that binds to the acetylcholine receptor on muscle cells, impairing muscle activity.

Dr. Mendelsohn’s team at UCSD screened thousands of monoclonal antibodies for their ability to block EGF receptor (EGFR) activation. By 1984, they had found one. They called it antibody 225. Later, a tweaked version of this antibody would become the drug cetuximab, which the US Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of colorectal cancer in 2004 and head and neck cancer in 2011.

Moving toward the Clinic

After coming to MSK in 1985, Dr. Mendelsohn further clarified how antibody 225 works. He showed, for example, that it curbed cancer growth not by activating the immune system but rather by preventing EGF from binding to its receptor. These laboratory studies set the stage for clinical testing in patients.

An early partner in this effort was a leading breast oncologist named Larry Norton, who had recently come to MSK from Mount Sinai Health System.

“I had known John for years, and one of the reasons that I decided to move to Memorial Sloan Kettering in the first place was that I knew of his scientific skills, his personal integrity, and his ability to get things done by motivating people,” Dr. Norton says. “There was lot of synergy between us.”

Enter Herceptin

Not long into their research on antibody 225, the MSK team was approached by a group of scientists from the California-based biotech company Genentech. They wanted to investigate the action of a similar antibody that Genentech had developed. This one targeted a receptor on cells called HER2.

Other scientists had recently showed that increased expression of the HER2 protein correlated with a worse prognosis in breast cancer. Using the same approach taken by Dr. Mendelsohn with EGFR, Genentech’s scientists had developed an antibody that could block HER2 signaling. They weren’t sure of its clinical value, however, and wanted the MSK scientists to study it.

A famous meeting between the MSK team and the Genentech scientists occurred in 1993. Sitting in the company’s offices in South San Francisco, they discussed the findings. Then, based on work from Dr. Mendelsohn’s lab, they refined a plan for a clinical trial to test what would become Herceptin.

“That was really a critical turning point because the company was having a lot of internal discussion about the development of the drug,” Dr. Norton says. “Can you imagine what a loss it would have been to the world, to the whole concept of precision medicine, if Herceptin never got developed properly?”

A Lifelong Learner

Although Dr. Mendelsohn’s principal interests were in research, he felt it was important to maintain his clinical skills. Late in his tenure at MSK, he decided he wanted to treat people with breast cancer. To get up to speed, he joined Dr. Norton’s breast cancer clinic as an unofficial medical fellow.

“Just imagine — this is the Chief of Medicine [at the time], and he’s working up cases and presenting them to me as if he were a fellow. That takes a special kind of leader, with a special kind of humility based on self-confidence,” Dr. Norton says.

Dr. Mendelsohn left MSK in 1996 to assume the presidency of MD Anderson. While there, he helped raise the stature of that institution and greatly expand its budget.

When he stepped down as MD Anderson’s president in 2011, he took on a position as director of a research institute at the center. Having been out of the lab for a while, Dr. Mendelsohn decided that he should bone up on the latest techniques. So he once again became a student, joining a lab at Harvard for a crash course in the newest science.

“John was a truly extraordinary man,” Dr. Norton says. “Working with him was one of the great pleasures of my professional life.”

John Mendelsohn was born in 1936 in Cincinnati. He attended Harvard College, where he studied with James Watson, co-discoverer of the structure of DNA. He obtained his MD degree from Harvard Medical School in 1963. In 2018, he was a recipient of the Tang Prize in Biopharmaceutical Science for his work on EGFR-blocking antibodies.