When immunotherapy works, it tends to work well: People with advanced cancer have seen their tumors shrink away and gained back years of life in some cases.

Drugs called checkpoint inhibitors that release the molecular brakes on the immune system have proven to be a particularly effective way to treat metastatic melanoma, lung cancer, and bladder cancer, among others. But these drugs, which can sometimes achieve long-lasting cures, work for only a fraction of the patients who receive them, leaving many without good options.

New research by Memorial Sloan Kettering scientists is helping to tackle the problem.

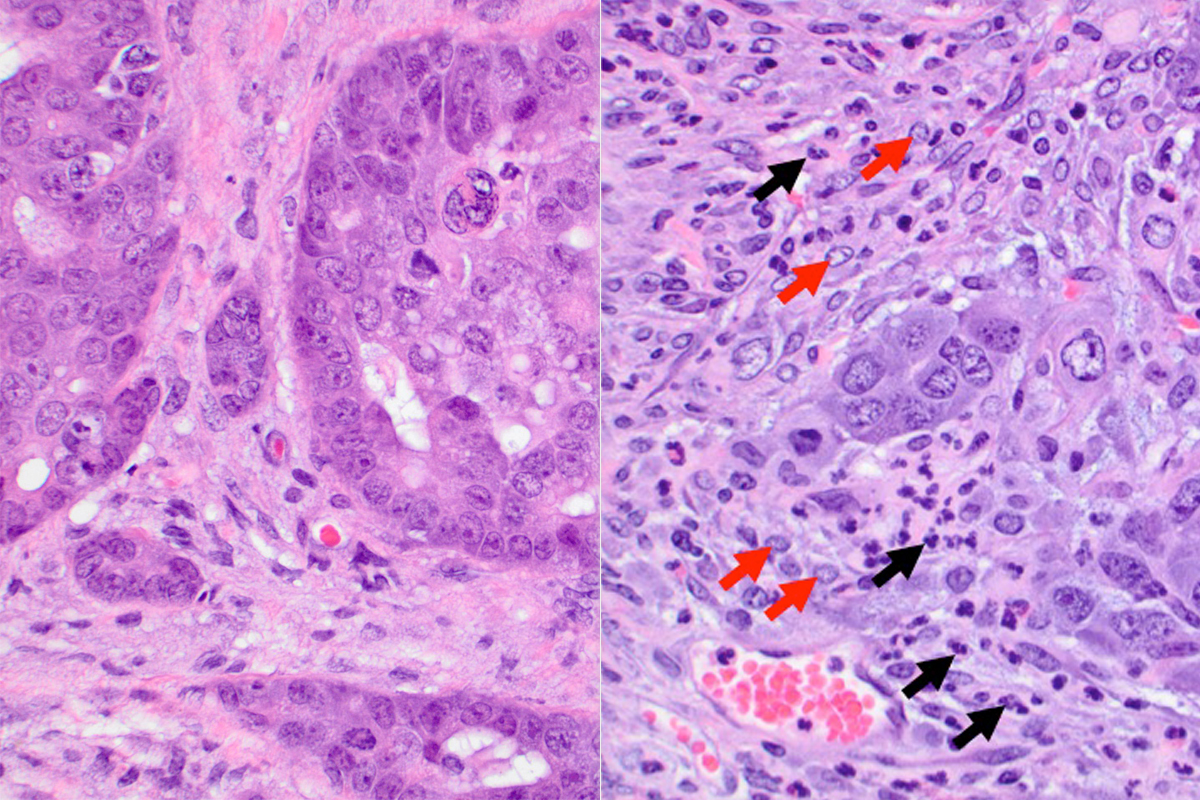

One reason why people may not respond to immunotherapy is that their tumors actively recruit immune-suppressing cells that, like a wet blanket, snuff out a fiery immune attack before it can get going. Not every tumor has these immune-squelching cells, but those that do tend to have a poorer prognosis.

The new research shows that an experimental drug can selectively target these suppressive cells and overcome the cancer’s stubborn resistance to these medications.

“We have shown that we can turn a tumor that is resistant to checkpoint blockade into one that responds,” says Taha Merghoub, a cancer immunologist in the Ludwig Collaborative Laboratory at MSK and co-lead author on the study, published today in Nature.

The discovery opens the door to a precision medicine approach to immunotherapy by identifying those patients whose tumors possess these troublesome cells and using therapies to specifically disarm them.

What’s more, the drug is currently being tested in a clinical trial, so the potential benefits of this therapy might be realized sooner rather than later. “This isn’t a pie-in-the-sky idea that might come to fruition ten years from now,” Dr. Merghoub notes. “This is something that can be tested now.”

Precision Immunotherapy

The MSK team used mouse models of cancer to show that the drug, called IPI-549, was effective at improving responses to checkpoint blockade therapy only in tumors that had an abundance of suppressive immune cells called tumor-associated myeloid cells. In tumors without these suppressive cells, the drug provided no benefit.

In mice with one type of suppressed tumor, checkpoint inhibitors administered alone resulted in complete remissions in only 20% of the mice; adding IPI-549 to the mix brought that number up to 80%. These tumor-free survivors were also able to rid themselves of new tumors transplanted into them, demonstrating lasting immune protection.

The results provide a rationale for using tumor biopsies — or perhaps less-invasive methods — to identify patients with tumors infiltrated by these cells, and to give the drug to those who are most likely to benefit.

“Being able to identify characteristics of tumors that explain why they don’t respond to treatment is one of our windows to introducing precision medicine into immunotherapy,” says co-lead author Jedd Wolchok, Chief of the Melanoma Service, Director of the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, and Associate Director of the Ludwig Center for Cancer Immunotherapy at MSK.

But the new research does more than explain a lack of response — it also offers a possible solution. “It’s one thing to know why someone will not respond to immunotherapy,” Dr. Wolchok says. “It’s another to have a drug in hand that can potentially overcome this hurdle.”

Dr. Wolchok suggests that targeting the suppressive cells with this drug might be a way to improve the efficacy of immunotherapy in certain cancer types — some breast cancers, for example — that are known to contain lots of them. But the benefit could potentially be felt across tumor types, he says, provided the tumors have these particular cells.

Productive Partnership

The new research is the result of a collaboration between MSK and Cambridge, Massachusetts–based Infinity Pharmaceuticals, the maker of the experimental drug. The drug blocks a particular molecule called PI3 kinase-gamma inside the suppressor cells, changing their behavior from immune suppressing to immune activating.

Dr. Merghoub says that Infinity had access to the laboratory data before the paper was published and this contributed to the company’s decision to pursue a clinical trial. Patients with a variety of solid tumor types are eligible to enroll in the phase I trial, which is being run at a select few hospitals in the United States, including at MSK, where it is led by medical oncologist Michael Postow.

The trial will evaluate the safety of IPI-549, first given alone and then in combination with an FDA-approved immunotherapy called nivolumab (Opdivo®), a type of checkpoint inhibitor.

“Having a preclinical paper at the same time that the clinical trial is actually accruing patients is unusual,” Dr. Wolchok says. “Typically we have to wait months or years before a laboratory discovery makes its way into a trial. Well, guess what? Clinical trials are happening now.”