A collaboration between Memorial Sloan Kettering researchers and an artist has produced both a new art form that allows viewers to see a seemingly invisible image and a promising test for cancer and diabetes.

The project grew out of a chance encounter between Sloan Kettering Institute scientist Daniel Heller, who develops nanotechnologies for cancer diagnosis and treatment, and visual artist Joseph Cohen.

“When I first saw Joseph’s work in an art gallery, I didn’t know how to approach it,” says Dr. Heller, who is also an associate professor at the Weill Cornell Graduate School of Medical Sciences. “But when he spoke about how he carefully chooses and combines materials to make new paints with new properties, I realized that his process is not so different from that of a materials scientist or engineer.”

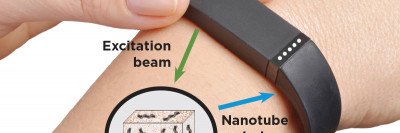

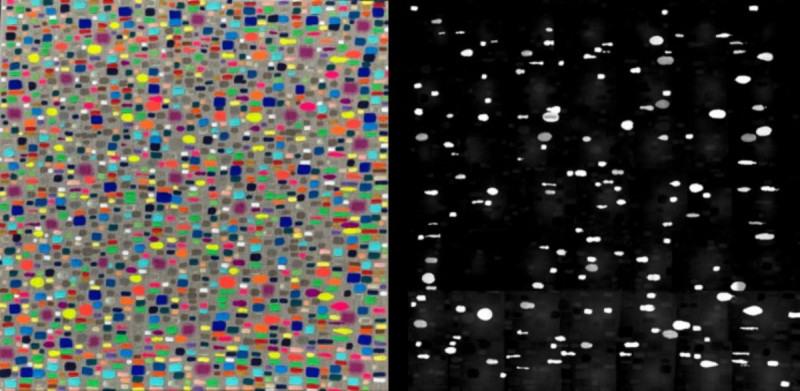

Dr. Heller’s lab uses carbon nanotubes in diagnostic sensors. The tiny tubes are so small that millions of them could fit on the head of a pin. The tubes absorb and emit harmless infrared light that is visible with special cameras, but not to the eye. Generally, Dr. Heller uses these materials to create tests that can help diagnose diseases. Together with Mr. Cohen, he developed a paint that is invisible to the eye but lights up through an infrared camera.

Mr. Cohen is now using the nanotube-based paints to produce paintings that look one way in normal light but another in near-infrared light.

“With these materials, I wanted to give viewers the ability to experience parts of the spectrum that they normally don’t have access to,” Mr. Cohen explains.

“He’s showing the public how these nanomaterials can do amazing things,” Dr. Heller says. “This understanding from the public is so important, and nanomaterials like these have many amazing possibilities to help people, from high-strength materials to electronics to medicine.”

Mr. Cohen’s nanotube-based paintings have been displayed in art galleries as well as at scientific meetings. “The works bring together scientists, artists, and members of the public where everyone learns something,” Dr. Heller says of the early exhibitions.

A Diagnostic “Sensor Paint”

Dr. Heller’s lab may have first developed the paints with Mr. Cohen to show people how nanotubes work, but eventually the scientists found them useful for cancer research. Januka Budhathoki-Uprety, a research scholar in the Heller lab, was working on a new test for microalbuminuria. This condition is an important early marker for several cancers, as well as for diabetes and high blood pressure. Microalbuminuria occurs when the kidneys leak small amounts of the protein albumin into the urine.

Although it is possible to detect microalbuminuria, the conventional method requires antibodies, which need to be stored carefully. Samples must then be sent to a specialized lab. The researchers wanted a test that would produce results faster and be useful in places far from a diagnostic lab.

Dr. Budhathoki-Uprety was initially using the carbon nanotubes to detect microalbuminuria in a test tube. However, she and Dr. Heller realized that, by incorporating the nanotubes into Mr. Cohen’s paints, they could build a much more versatile sensor.

“When we made the nanosensors into a paint, we found that they worked perfectly to detect albumin and could be painted on any surface,” Dr. Budhathoki-Uprety says.

In the journal Nature Communications, the researcher-artist team reported that the nanosensor paint reliably detected microalbuminuria in urine samples from people with cancer.

“We initially thought that, in working with an artist, we would make art to shed a little light on our science for the public,” Dr. Heller says, “but the collaboration actually taught us something that could help us shine a light on cancer.”