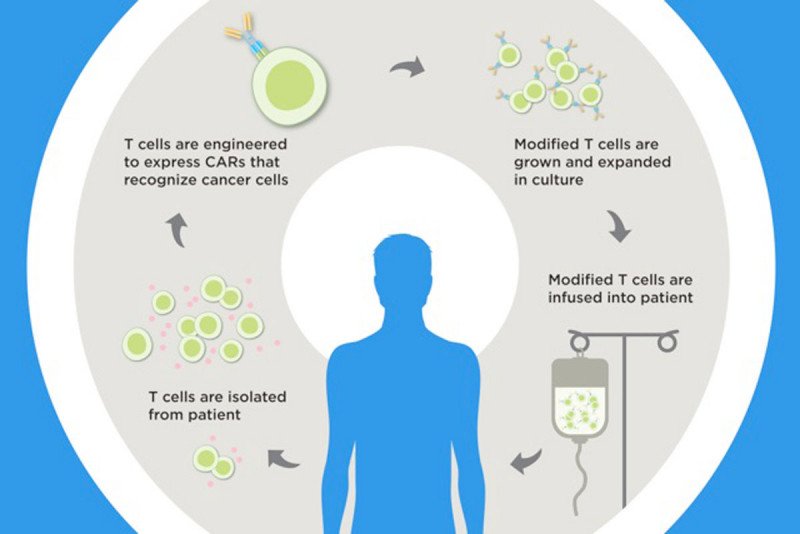

In CAR T cell therapy, a patient's own immune cells are genetically engineered to find and fight cancer. Memorial Sloan Kettering scientists are developing ways to make this treatment safer.

CAR T cell therapy is helping a growing number of people survive aggressive blood cancers. The treatment, recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, uses genetically engineered versions of a person’s own immune cells to find and fight cancer. But it comes with some equally formidable potential side effects.

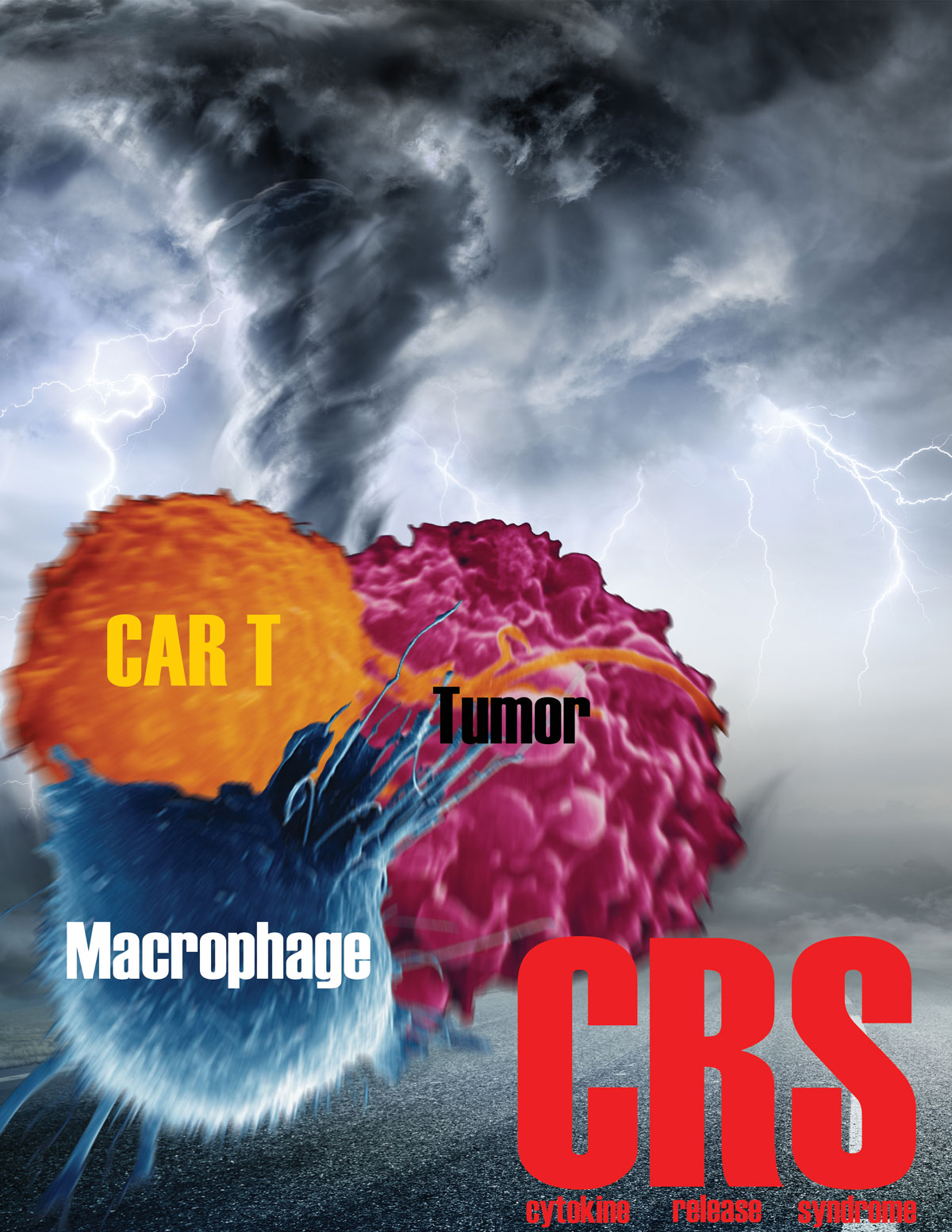

One of the most feared is cytokine release syndrome (CRS), a surge in the production of immune-stimulating molecules. It can lead to dangerously high body temperatures, low blood pressure, and breathing difficulties that can be fatal. Medicines do exist to treat CRS. But the complication remains a hurdle to the therapy becoming a routine, affordable part of standard medical care.

A new study from researchers at the Sloan Kettering Institute identifies the cellular culprit responsible for this side effect. Somewhat unexpectedly, it’s not the souped-up immune cells themselves.

“It has long been assumed that CAR T cells themselves cause CRS,” says immunologist Michel Sadelain, who pioneered CAR therapy and now directs the Center for Cell Engineering at MSK. “But what we have found is that another immune cell type called a macrophage is largely to blame for this side effect.”

The researchers made their discovery in a mouse model of CRS that they created in the lab. The model has many similarities to what happens in patients receiving CAR therapy, and so is a good way to ask questions about the underlying biology.

“Prior to this work, no reliable mouse model of CRS was available,” says Theodore Giavridis, a Weill Cornell graduate student working in the Sadelain lab who conducted this research as part of his thesis work. “That limited our ability to ask questions and test hypotheses about what is causing CRS.”

Now that scientists know what cell types are involved, they can think about ways to more effectively treat or even prevent CRS.

Homing in on a Bad Actor

CRS is sometimes called cytokine storm. Of all the cytokines that get whipped up after a CAR T cell infusion in people, the one that was known to cause problems is interleukin-6 (IL-6). Currently, the best way to bring CRS under control is to administer a drug that blocks IL-6 activity.

Although T cells can make IL-6, the team found that those cells are not the predominant ones pumping it out in CAR T cell–treated mice. Rather, it’s macrophages congregating in the area around the tumor and around the CAR T cells that are producing it.

“Macrophages are kind of the poster child cell type for making IL-6,” Mr. Giavridis says.

To prove that the macrophages are the main culprit of CRS, the team approached the problem from two angles. First, they engineered CAR T cells that could specifically activate macrophages. They found that CRS in the mice got significantly worse in this case. When they blocked macrophage activity, however, the severity of CRS was markedly diminished.

Translational Lessons

Cytokine release syndrome, sometimes called cytokine storm, is caused by interactions between CAR T cells, macrophages, and tumor cells. Credit: Giavridis/Sadelain

While the study was performed in mice, the results have important translational implications.

Macrophages require a molecule call IL-1 to do their work. Blocking this molecule provides a way to tamp down macrophage activity, and therefore CRS.

There are two main ways doctors could go about blocking IL-1, Mr. Giavridis says. They could give patients drugs called IL-1 blockers, which are readily available, safe, and FDA approved. This is what doctors would likely try first, he notes. The medical team at MSK is already preparing to test IL-1 blocking in the clinic.

The second approach would be to engineer CAR T cells that make and secrete a blocker of IL-1 activity. This is a more high-tech approach, but one that could have more appeal in the long run, since the means to prevent the side effect would be built in to the treatment.

The team tested both approaches in their study and found both were effective at blunting CRS without impairing the effectiveness of the CAR T cells.

CARs — chimeric antigen receptors — are genetically engineered proteins. The CARs used in this study target a molecule on B cell cancers called CD19.

A Finding with Broad Scope in CAR Therapy

The FDA approved two CAR T therapies in 2017, for the treatment of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. CRS has most commonly been seen in these two cancer types.

But the side effect is not likely to be limited to just those. “CRS may occur in CAR therapy for other cancers,” Dr. Sadelain says. “There is keen interest in finding a definitive solution to CRS, so that CAR therapy can be more broadly applied.”

“I think what’s exciting is that we’re starting to get clear answers about the role of different cell types in CAR T side effects,” Mr. Giavridis says. “And now we have a model in which we can test hypotheses going forward.”

The findings appear today in the journal Nature Medicine. An accompanying editorial appears in the same issue.