A recent study by Memorial Sloan Kettering researchers is a step in the direction of improving strategies to find matching donors for leukemia patients who need a bone marrow transplant. Published in the August 30 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, the findings indicate that some people are less likely to redevelop their disease after a transplant if their donor carries certain genetic traits.

Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) is a complex but often lifesaving treatment for a number of cancers and blood disorders, including acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). The procedure involves eliminating a patient’s diseased bone marrow using chemotherapy or radiation and renewing it with healthy, blood-forming stem cells from a donor or from donated umbilical cord blood.

The success of BMT depends in part on finding a donor who is a “good match” — someone who has certain genetic features in common with the patient. When matching patients with potential donors, doctors currently examine the DNA sequence of a group of genes called HLA, which varies among individuals. If a donor’s HLA genes closely resemble those of the patient, this reduces the risk of post-treatment complications such as graft-versus-host-disease, in which the transplanted cells recognize the patient’s own cells and tissues as foreign, and attack them.

The new study now suggests that an additional type of gene known as KIR might influence the long-term effectiveness of transplants in patients with AML.

“We found that specific combinations of donor KIR and patient HLA genes are linked to improved transplant outcomes, with patients living disease-free longer,” says medical oncologist Katharine C. Hsu. She led the research together with Bo Dupont, a member emeritus of the Immunology Program in the Sloan Kettering Institute.

“This knowledge could make it possible to refine the selection of donors for some patients, for whom more than one HLA-matched donor is available, by testing for KIR genes as well as for HLA,” adds Dr. Hsu.

Harnessing Natural Killer Cells

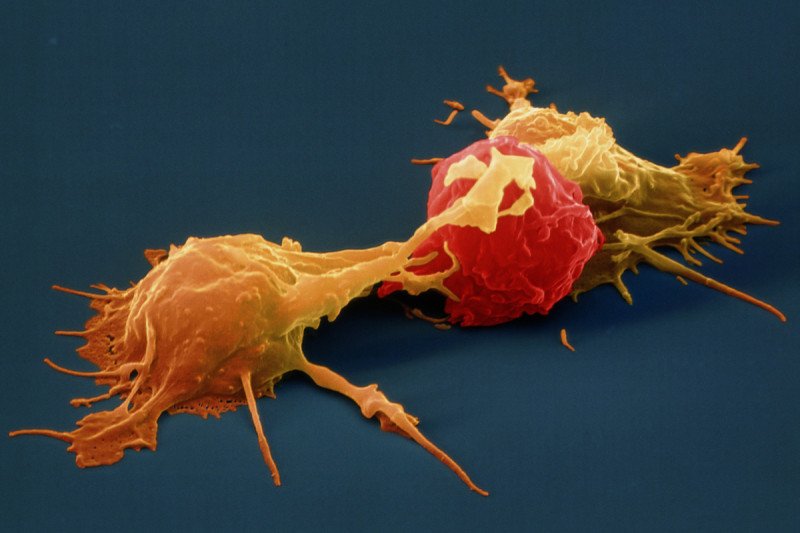

She explains that the reason why certain combinations of donor HLA and KIR appear to be beneficial in a transplant setting has to do with the function of immune system cells called natural killer (NK) cells, which have the ability to recognize and kill tumor cells.

“After a patient receives a bone marrow transplant from a donor, NK cells and other immune cells form naturally from the donor’s stem cells,” Dr. Hsu says. In some patients, such NK cells help prevent leukemia from coming back by reacting against newly developing cancer cells and eliminating them.

The KIR genes make proteins called killer cell Ig-like receptors, which are found on the surface of NK cells. As with HLA, the KIR genes vary between people. Some individuals carry a gene called KIR2DS1, which produces a receptor that has been shown to activate the cancer-fighting function of NK cells under certain conditions.

“We posited that transplants from donors who have this favorable gene might provide better protection from relapse because NK cells in the transplant have an enhanced capacity to react against leukemia cells and kill them,” explains Dr. Dupont.

Making Good Matches Better

To test this hypothesis, the investigators performed a retrospective study of 1,277 cases in which AML patients had received a bone marrow transplant from an HLA-matched donor.

The researchers used banked blood samples to perform DNA testing of each donor’s KIR genes. They discovered that among patients who had received transplants from donors carrying KIR2DS1, the disease returned less often after the treatment than in patients whose donor did not carry the gene.

The beneficial effect of KIR2DS1 was observed only in patients who carried specific variants of the gene HLA-C. The researchers note that more than 85 percent of the patients in the study have such gene variants, while approximately one-third of donors have KIR2DS1.

Dr. Hsu and her colleagues are now planning a clinical trial to explore whether their findings might translate into more-advanced genetic tests to match up patients and donors for BMT.

In addition, she is hoping that basic research will reveal other gene combinations that may result in more favorable transplant outcomes for patients.

“HLA testing is currently the gold standard, but we may one day be testing for additional genes,” she notes. “As we learn more about how NK cells function in health and in disease we will increasingly get better at finding the best possible match for each patient, improving the chance of a cure.”