The history of medicine is full of unanticipated findings. Penicillin, x-rays, and even aspirin came about by chance.

Memorial Sloan Kettering scientists recently made one such discovery: A common, well-studied cancer gene also plays a key role in a seemingly unrelated disorder of blood vessels called venous malformation (VM).

VM is a rare condition that affects one in 10,000 people. The deformed blood vessels that characterize the disease cause pain and disfigurement and can lead to problems with the nervous, muscular, and digestive systems.

MSK’s findings led to the first-ever genetically engineered mouse model for VM, as well as promising avenues for treating this potentially very serious condition with targeted therapy.

“Such a serendipitous finding almost never happens, because research is so driven by the hypothesis,” says MSK cancer biologist Maurizio Scaltriti. “This is one of the few cases in 2016 when you can still see one of those completely accidental, penicillin-like findings.”

An Unexpected Finding in Lab Mice

Dr. Scaltriti and his colleagues in MSK Physician-in-Chief José Baselga’s laboratory were studying the formation of endometrial cancer in mice. The rodents were engineered to carry mutations in a gene called PIK3CA, which have been found in many tumor types. Unexpectedly, many of the mice developed symptoms that included paralysis and bulging veins under their skin.

“We knew right away that our findings were not a coincidence,” says graduate student Pau Castel, who was leading the research.

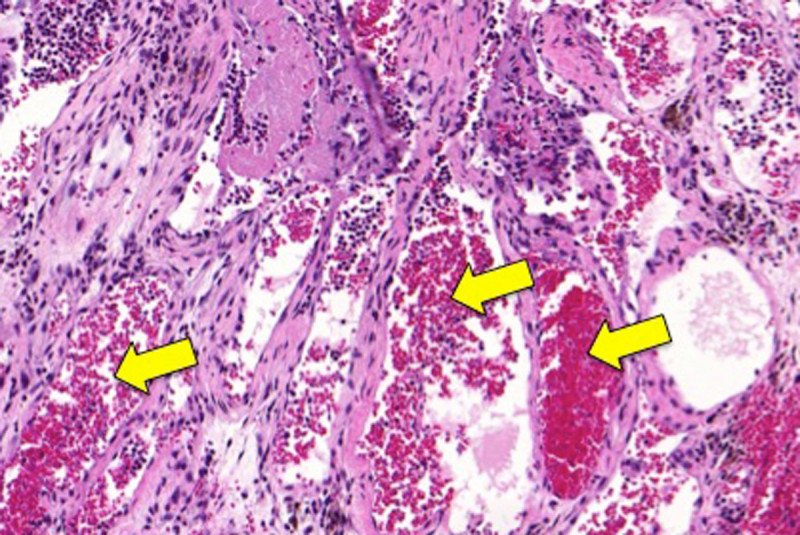

Further investigation revealed that malformed blood vessels around the animals’ spines were causing the paralysis. Such blood vessels, as well as the bulging veins, are hallmarks of VM.

Zeroing In on a Rare Disease

Once the researchers determined the mice were experiencing VM, they looked for a connection between PIK3CA mutations and the disease. Further studies, including genetic analysis of 32 MSK patients who had VM, confirmed the relationship. The team determined that about a quarter of all cases of VM are caused by PIK3CA mutations.

For Dr. Baselga, who was senior author of the study, there was another surprising finding. He acknowledges that the team didn’t know much about VM, but they were able to take advantage of a hard-to-believe coincidence. “It turns out that I knew one of the world’s leading experts in the condition — my sister Eulalia Baselga, an academic pediatric dermatologist in Barcelona,” he says. “So it was easy. I simply called her up. She told me, ‘I’ve been waiting for something like this for a long time. It opens up a true understanding of the disease.’”

Since the laboratory was already studying targeted therapies that block PIK3CA mutations in cancer, they prepared topical creams containing the drugs and applied them to the mice, which resulted in a measurable decrease in VM. The researchers confirmed that the drug in the cream was targeting VM in the same way it attacks cancer cells, by reducing the growth of defective cells and killing those that are already there.

Further studies in the lab are needed before these treatments can be evaluated in people. But because current therapies for VM don’t work very well, the investigators hope they can be available to patients quickly.