A critical aspect of growth control is to ensue that all organs attain sizes that have the correct proportions with other organs. The developmental signaling pathways and cellular processes that control organ size also can be involved in recover from injury (Roselló-Díez, 2015). Furthermore, during evolution the degree to which these mechanisms are active has likely changed and account for the distinct body sizes and organ proportions observed in different species. On the other hand, when growth-signaling pathways are unchecked, cancers can develop. We recently developed a novel model to study growth regulation pathways using the bilateral limbs as an example, as by altering growth of only the left limb the right limb serves as an internal control (Roselló-Díez, 2017, 2018; Ahmadzadeh, 2020). We have also studied regeneration and cancer of the prostate (Peng, 2012; Yang, 2017). Currently, we have two main projects focused on determining the roles of SHH-signaling in cerebellar growth regulation and cancer.

Sonic hedgehog regulates developmental growth and adult stem cell behaviors

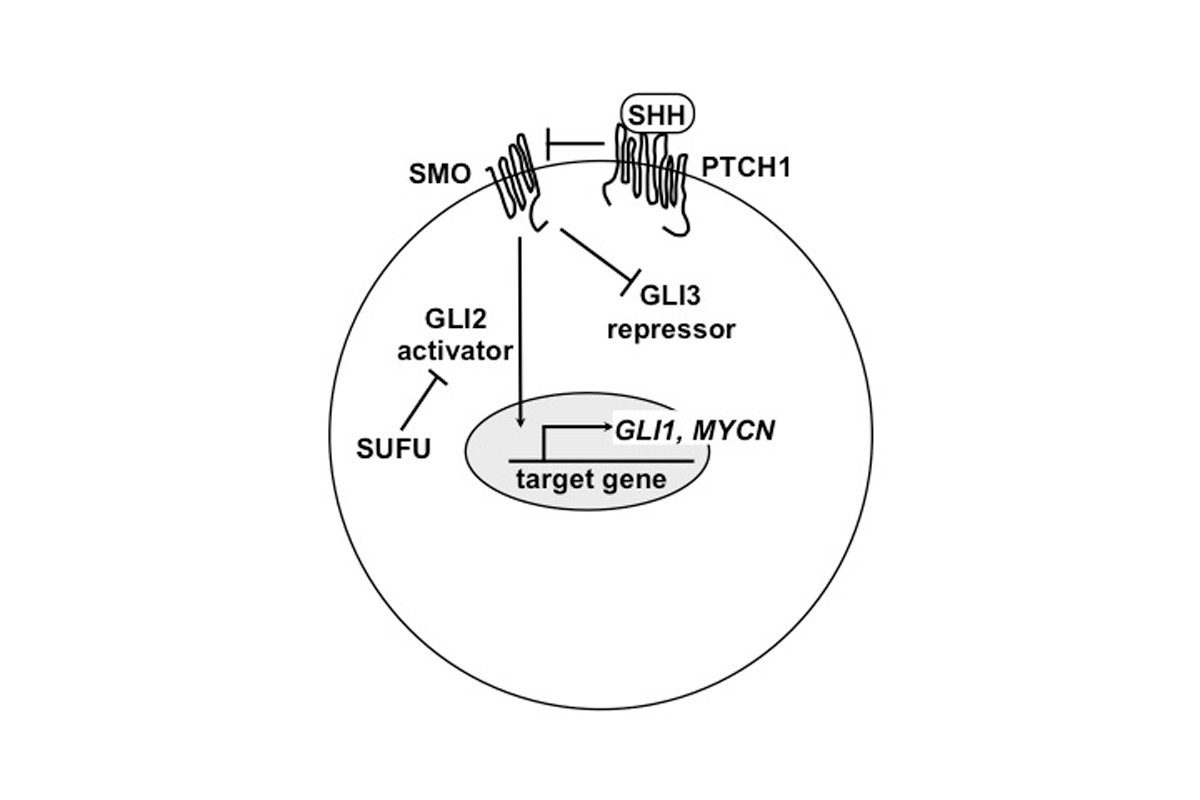

The secreted factor sonic hedgehog (SHH) that mediates signaling through three GLI transcription factors (Fig. 3) is critical for development of most mammalian organs and maintains the pluripotent state of several adult stem cell populations. Human mutations that reduce SHH signaling cause a variety of developmental defects, whereas inappropriate activation of signaling contributes to cancer (Petrova, 2014; Peng, 2015). To study the in vivo functions of the GLI transcription factors, we generated an array of mouse targeted conditional and knock-in alleles. By analyzing the embryonic phenotypes of our mutants in the limb and nervous system, we uncovered a universal rule for GLI function: HH signaling modifies GLI2 to form an activator and GLI3 to attenuate formation of a repressor (Fig. 3). Moreover, high level SHH signaling induces transcription of Gli1 (Bai & Joyner, 2001; Bai, 2002, 2004). We have taken advantage of Gli1 being a HH target gene to identify cells undergoing high HH signaling, and follow the fate of their progeny using genetic inducible fate mapping (Fig. 4; Joyner, 2006). In particular, we used our Gli1CreER allele to identify and fate map stem cells in a variety of adult tissues (forebrain, skin and prostate) (Ahn, 2004, 2005; Brownell, 2011; Peng, 2012). For example, we discovered that in the skin, SHH is secreted by peripheral nerves, and the nerves are required to maintain hair follicle bulge stem cells in a plastic state, able to be reprogrammed into interfollicular skin stem cells (Brownell, 2011). Other groups have since found nerves are a critical source of HH ligands in several adult organs.

SHH coordinates expansion of multiple cerebellar progenitors

In the cerebellum, SHH drives the tremendous expansion of progenitors after birth in mouse that is responsible for folding of the cerebellar surface (Fig. 1D and Movie 1). Accordingly, we found that ablation of SHH signaling results in a hypoplastic cerebellum, as SHH is required for expansion of granule cell progenitors, the most numerous cell type in the brain (Corrales, 2004, 2006). On the other hand, SHH signaling is elevated in the SHH subgroup of medulloblastoma for which the cerebellar granule cell progenitors, which proliferate for almost 1 year after birth in man, are the main cell of origin. SHH also regulates expansion of ventricular zone-derived progenitors (NEPs) that give rise to interneurons and astrocytes. Thus, SHH is a key growth regulator of the postnatal cerebellum. One aspect of our research addresses how SHH coordinates proliferation and differentiation of several distinct progenitor populations in the cerebellar cortex. Using our novel mosaic mutant analysis technique (MASTR; Lao, 2012), we uncovered that a primary role of SHH in NEPs is to maintain them in an undifferentiated state (Wojcinski, 2017, 2018; Tan, 2018), similar to our finding for adult stem cells in the subventricular zone of the forebrain (Petrova, 2013). Similar studies are underway for the other progenitor populations.

Timing of and type of initiating mutation stratify SHH-medulloblastomas

Medulloblastoma (MB) is the most common malignant brain tumor in children. Although the majority of children with MB survive to adulthood, the quality of life of survivors is greatly compromised due to the toxicity of combined surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. MB is a heterogeneous disease that was divided into 4 subgroups based on their molecular signatures. As the current SHH inhibitors in the clinic are only effective in a minority of SHH-MB patients and all patients develop resistance, new drug targets are needed to improve survival and minimize the significant side effects of current therapies. A recent study further subdivided SHH-MB into 3 subtypes based on age of presentation, as particular genetic lesions are specific to infants (SUFU), children (TP53 associated with amplification of GLI2/MYCN) and adults (SMO)(Kool, 2012; and see Fig. 3). However, patients of all ages have mutations in the Gorlin syndrome gene PTCH1. The most recent classification of MB divides SHH-MB into 4 subtypes, with TP53 mutations defining a group with poor prognosis (Cavalli, 2014). We have developed mouse models of SHH-MB (Suero-Abreu, 2015; Tan, 2018), including using MASTR to initiate mutations in SMO or PTCH1, with or without mutations in Trp53, and identified differences in the biology of the tumors. Microarray analysis of genes expressed in GFP-labeled mutant granule cell precursors that progress to form tumors, compared to those that regress or wild type cells have identified candidate genes that underlie tumor progression. We have teamed up with leading experts in the genetics and pathology of human MBs, to determine the extent to which human tumors with the same mutations have similar tumor characteristics (Vladoiu, 2019). In addition, we are using functional assays in granule cell precursors with MB activating mutations to determine which of the genes identified are required for tumor formation and/or progression, with the goal of identifying candidates for novel therapies specific to SHH-MB subtype-specific patients. We are also using similar approaches to determine the role of immune cells in the microenvironment of mouse and human SHH-MBs on tumor progression (Rallapalli, 2020; Tan, 2021). Our studies should uncover which mice best model particular subtypes of human SHH-MBs for preclinical testing, and contribute to stratification of patients for targeted therapy.

Figure 3. SHH canonical pathway with protein locations indicated in a cell (nucleus grey oval). The four prevalent mutations in SHH-medulloblastoma are loss of PTCH1 (seen in all ages), SUFU (infants) and TP53 (associated with amplification of MYCN/GLI2 in children), or SMO activating mutations (e.g. SmoM2 mainly seen in adults).

Figure 4. Genetic inducible fate mapping allows temporal and cell specific control over marking of cells and determination of cell behaviors. (A) Schematic of a cell (grey with nucleus indicated by white oval) in a transgenic mouse carrying a Gli1 allele in which an inducible stie specific recombinase (CreER) has been inserted into the first coding exon and a ubiquitously expressed R26 gene in which has been inserted a ‘stop’ sequence (that stops transcription), which is surround by loxP sites (blue ovals – DNA sequence Cre binds), and has a downstream cDNA encoding a red (tomato color) fluorescent protein (tdTom). When tamoxifen (TM) is administered to the mouse, it binds CreER, releasing it from being bound to heat shock protein (HSP) so that it can enter the nucleus, bind the loxP sites, and induce recombination of the loxP-stop-loxP (LSL) sequence resulting in deletion of the ‘stop’. The R26 gene can now transcribe tdTom, making the cell fluoresce red. (B) Schematic showing two sister cells, only one of which (tomato color) has the two transgenes shown in (A). After administration of tamoxifen, tdTom expression is induced, and fate mapping of the labeled cells allows the different behaviors of the progeny of the two cells to be observed.