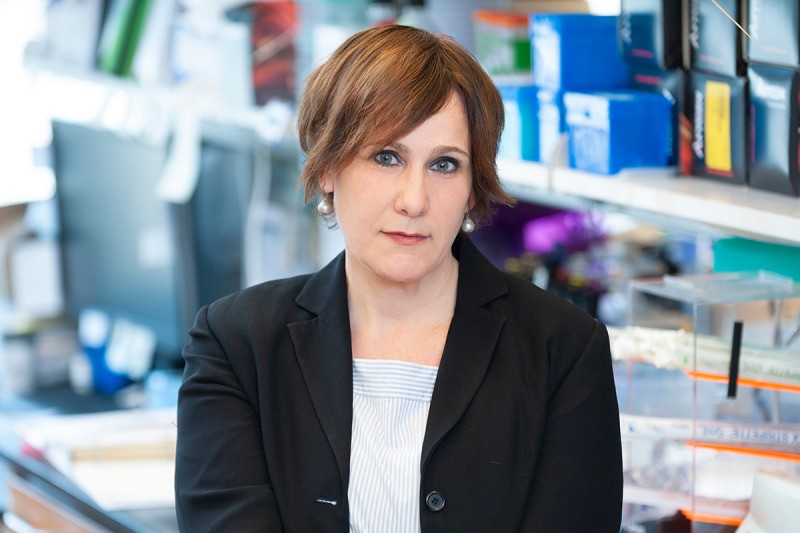

When tumor immunologist Andrea Schietinger started her lab at the Sloan Kettering Institute in 2015, she never expected to be working on a topic as distant from cancer as diabetes.

Dr. Schietinger’s research specialty is understanding why immune cells called T cells sometimes fail to fight cancer. Like soldiers surrendering to the enemy, they lay down their arms even before they’ve really tried to fight. Scientists believe this is one reason that immunotherapies may fail to help patients.

After several years working on this problem, Dr. Schietinger (Catherine and Frederick R. Adler Chair for Junior Faculty) thought she understood what was plaguing the sluggish cells: Their “killing” genes had been shut down — wrapped up tight like a zip file on your computer. If she could find a way to open these genes back up, it might help improve immunotherapies. However, nothing that she and her colleagues did to the cells could prod them into action.

Faced with an intellectual brick wall, she began to think outside the box.

“When I asked myself, ‘What is a role-model T cell — one that never shuts down its genes and can keep killing endlessly?’ ” says Dr. Schietinger, “I realized it is a T cell like we find in autoimmune diseases. Why? Because T cells in autoimmune diseases never stop killing and can destroy entire organs.”

Take Type 1 diabetes, for example. In Type 1 diabetes, the T cells turn against the body’s own pancreas, killing cells relentlessly. The pancreas is the organ that makes insulin; people who can’t make insulin cannot regulate their blood sugar, with dire consequences. Left untreated, it can be fatal.

“These autoimmune T cells are really fantastic killers,” Dr. Schietinger says. “I thought to myself, ‘If we can understand how they remain active, then maybe we can use that knowledge to build a better cancer-fighting T cell.’ ”

That was four years ago. Since then, and with support from a prestigious National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director’s New Innovator Award and a grant from the Cancer Research Institute, Dr. Schietinger has made great headway in understanding what makes autoimmune T cells such great fighters.

What she’s found is something that no one — not even those working in the autoimmune field — had ever previously seen.

T Cell Factories

Like all immune cells, autoimmune T cells travel through the body in lymphatic vessels that periodically intersect with lymph nodes, where they are alerted to potential threats. From these lymph nodes, T cells then travel into tissues, where they go on the attack. In the case of diabetes, the T cells travel from a lymph node near the pancreas into the pancreas itself, where they find and kill insulin-producing cells.

Dr. Schietinger’s team used genetically engineered mice to study the T cells in diabetes. By closely following these T cells along their journey through the body, they were able to see that the T cells in the lymph node had some unique properties. For one, they looked a lot like stem cells, which have the unique ability to not only regenerate themselves but also generate new T cells.

These new T cells, the scientists found, leave the lymph node and travel to the pancreas. But surprisingly, they don’t last very long there. Instead, they kill a few insulin-producing cells and then they themselves die. But soon a fresh crop of autoimmune T cells appears in the pancreas, ready to continue the fight. How? Because the stem T cells in the lymph node constantly make new autoimmune T cells and never stop making them.

The unusual findings provided an answer to the longstanding puzzle of why autoimmune T cells don’t get exhausted in the same way tumor-specific T cells do: They are continually being replaced.

Such a stem-like T cell population has never before been implicated in diabetes, and Dr. Schietinger thinks that it could be a common feature of other autoimmune diseases as well.

She and her team are now looking for ways to take advantage of these regenerative powers of autoimmune T cells in the fight against cancer. Ultimately, they hope to endow tumor-specific T cells with the increased stamina of their autoimmune cousins, to help them fight cancer for longer and save more lives.