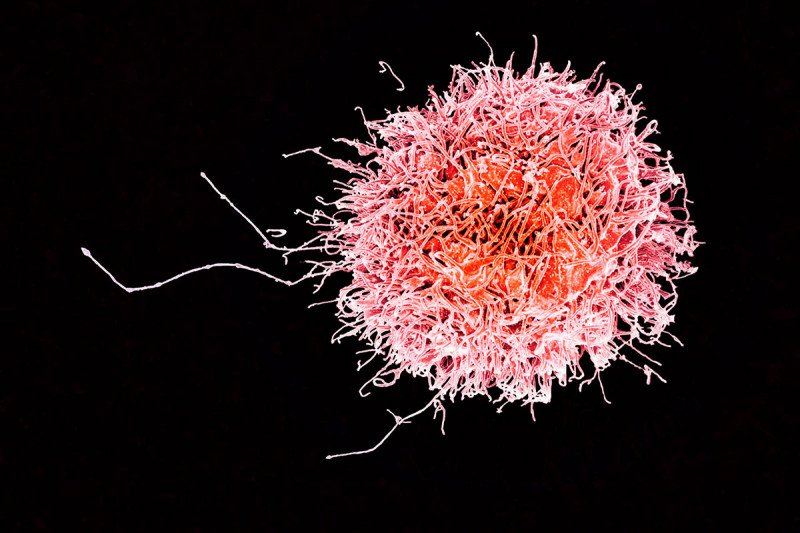

The goal of most cancer-fighting drugs is to kill tumor cells. But there’s a fate short of death that can befall a cancer cell, something called senescence. In this state of permanent arrest, the cells continue communicating with their neighbors, but they stop dividing.

Researchers at the Sloan Kettering Institute have found that a particular drug combination can put cancer cells into this senescent state, with the unexpected result that the immune system is then prodded into offing them.

Drugs that don’t kill cancer cells but do stop their division are called cytostatic. The results from this study, published on December 20 in the journal Science, suggest that cytostatic drugs deserve a second look as a potentially powerful approach to cancer treatment.

“Cancer drugs that merely halt the proliferation of cancer cells have not been widely pursued, owing to the fact that we generally want tumors to shrink,” says Scott Lowe, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator who is Chair of the Cancer Biology and Genetics Program at SKI and the senior author on the new paper. “However, if tumor cells can be induced to undergo senescence, they can then provoke an immune response,” which can lead to the tumor shrinking.

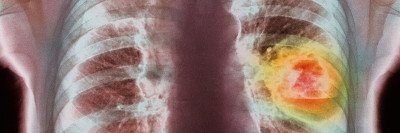

What’s more, the drug combination works against a particularly deadly class of tumors, those with mutations in a gene called KRAS. Few good therapy options currently exist for cancers with KRAS mutations.

The scientists performed their study using human cell lines and tumor tissue as well as lab mice. They hope to extend the research through a clinical trial in people with KRAS-mutated lung adenocarcinoma.

It Takes Two (Targeted Therapies) to Make a Thing Go Right

The scientists tested two drugs: trametinib (Mekinist®) and palbociclib (Ibrance®). Trametinib is a MEK inhibitor, and palbociclib is a CDK4/6 inhibitor. Both medicines are targeted therapies that block signals that cue cells to divide. The team found that when given together, the drugs shrank tumors and increased how long the mice survived. Neither drug given alone had these effects, suggesting that the two work synergistically.

The team did the first experiments in mice with a functioning immune system. To tease out a direct tumor-killing role of the drugs from a possible indirect effect on the immune system, the scientists redid the experiment, only this time in mice engineered to lack immune cells. To their surprise, the effectiveness of the drug combination was dramatically reduced, indicating that the immune system was playing a pivotal role.

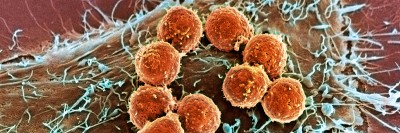

Once they knew the immune system was involved, they set about seeing which immune cells were doing the killing. Somewhat unexpectedly, they found that T and B cells — the cells of adaptive immunity, which learn to recognize unique threats — were not responsible for the effect. Rather, an innate immune cell called a natural killer (NK) cell was responsible. (The innate immune system includes the defenses we’re born with.)

NK cells are primed to recognize stressed-out cells, and they are some of the body’s earliest lines of defense against cancer. NK cells are thought to prevent microscopic metastases from sprouting in the body, but they tend to be less of a factor after tumors form. In this case, however, the team found that the NK cells were fighting fully formed tumors.

“Our study is one of the few that show that an established primary tumor can be resensitized to NK cell attack,” says Marcus Ruscetti, a postdoctoral fellow in the Lowe lab and the lead author on the new paper.

Following drug treatment, the senescent tumor cells actively secrete molecules that recruit NK cells and allow them to be recognized as targets for killing, he explains.

Hope for “Undruggable” Cancers

Historically, the mutated KRAS protein has been thought of as “undruggable” because it’s been difficult to design medicines that can block its action directly. No effective drugs for KRAS-driven cancers have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The new results raise the hope that effective therapies might yet be possible by enlisting the immune system to fight senescent tumor cells.

The team is now looking to combine cytostatic drugs with the immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors. They hope that this pairing will further enhance the immune system’s attack on tumors.