About Your Transsphenoidal Surgery

Located just beneath the brain, the pituitary gland is sometimes called “the master gland” because it regulates most of the hormones in the body. Approximately 20 percent of people have some sort of abnormal growth in this gland. The vast majority of them do not require treatment, but they do need proper evaluation and monitoring. Specialists at Memorial Sloan Kettering’s Multidisciplinary Pituitary and Skull Base Tumor Center have the expertise needed to take care of all types of pituitary tumors. This includes rare, aggressive ones. Neurosurgeon Viviane Tabar, head and neck surgeon Marc Cohen, and neuroendocrinologist Eliza Geer see people with pituitary tumors every week. Here, they talk about why specialized care for these people is crucial.

What types of tumors form in the pituitary gland?

Dr. Tabar: These tend to be slow-growing tumors. The majority are not cancerous. Put simply, there are two major types of pituitary tumors: those that secrete hormones and those that don’t. The majority of the nonsecreting pituitary tumors we see don’t need treatment. But they do need follow-up, and they require surgery if they get too big. The ones that secrete often require surgery and almost always require medicine to balance out hormone levels.

When are these tumors considered cancer?

Dr. Geer: Technically, a pituitary tumor is defined as a cancer if it metastasizes, or spreads, to other parts of the body or the brain. Those tumors are very, very rare — about a fraction of 1 percent. But about 15 to 20 percent of pituitary tumors that don’t metastasize still behave aggressively. They might come back after surgery, require multiple treatments, or be resistant to treatments.

Dr. Tabar: Just because a tumor is benign doesn’t mean it is not causing problems.

What’s the process for someone coming to the Multidisciplinary Pituitary and Skull Base Tumor Center?

Dr. Cohen: A patient calls and is connected with a very experienced nurse who coordinates a day when a patient can come in and see all of us. It’s important to see the neuroendocrinologist, the neurosurgeon, and the head and neck surgeon on the same day so we can come up with a plan. That’s better than seeing one doctor this day, another in a few days. Patients tend to be very satisfied by that approach, which is really unique to our program.

Dr. Geer: There’s a lot of coordination prior to that visit. By the time a patient sees us, we’re all prepared to discuss care. It’s essential for people with a relatively rare disease like these tumors to have a team with expertise and close collaboration. I think some of our patients are a little reluctant to come to MSK at first because it’s a cancer hospital. But when they’re here, I think they realize that this is a great place to be for their diagnosis and treatment.

What is the surgery to remove a pituitary tumor like?

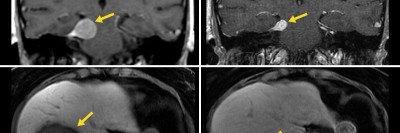

Dr. Tabar: It is a surgery that is performed through the nose, not requiring any visible cuts. Dr. Cohen and I work together — he develops the approach to get us to where the tumor is and then I remove it. We use surgical navigation, which is sort of like a GPS system that tells us where we are, so we can be aware of our proximity to important parts of the head. At MSK, we often do the operation in a room with an MRI machine. Before we finish surgery, we already know if we’ve removed the entire tumor or if we’re purposely leaving something behind because the location is too close to crucial areas in the head.

Dr. Cohen: The tumor size and complexity determine the length of the surgery, which can be anywhere between two and five hours. After surgery, people stay in a special unit that’s only for neurosurgery patients for two to three days. It’s a relatively straightforward recovery.

Dr. Tabar: After surgery, we need to know if we caused them any hormone deficits that need to be addressed. And of course, part of the postsurgical care is making sure that things are healing properly. Having our clinic together makes it easy for patients to get the appropriate follow-up. When we do later follow-ups, we can look at the MRI remotely and communicate with patients about the result, or they can come back here.

Is radiation therapy used for pituitary tumors?

Dr. Tabar: Radiation therapy is an important tool. But it is not required for everyone. For the majority of nonsecreting tumors, surgery alone is adequate. Sometimes we have patients who have residual tumor cells because the tumor is growing in a place where surgery could cause problems for the patient. We usually discuss treatment plans for these patients at our pituitary tumor board, which is a biweekly meeting to develop plans for challenging cases. In addition to us, it includes neuro-oncologists and radiation oncologists. Sometimes radiation is needed, especially when a tumor shows evidence of regrowth.

Dr. Cohen: We can also offer a special form of radiation called proton therapy. This produces fewer side effects than traditional radiation. It is available for appropriate patients at the New York Proton Center.

What advances in the field excite you?

Dr. Geer: We’re involved in a number of clinical trials studying new therapies for hormone-secreting tumors that cause Cushing’s disease or acromegaly. We’ve also opened a trial to treat aggressive pituitary tumors. We were seeing that in people treated with immunotherapy for other cancers, a very common side effect was inflammation of the pituitary gland. So the pituitary was responding to these medicines in some way, and we wanted to utilize that knowledge for our patients. One of our patients with an aggressive cancerous tumor had a very dramatic response on immunotherapy: More than 90 percent of her metastasis regressed, and so did more than 50 percent of her original tumor.

Dr. Tabar: This is an important innovation. People with these tumors don’t have any other options.

Why is it important to involve people in their own care?

Dr. Tabar: Patients have good ideas and very insightful comments. We have to raise our own awareness of their needs and provide a platform for them to discuss it.

Dr. Cohen: One thing unique to our program is patient-reported outcomes. We ask patients about a wide range of symptoms before, during, and after treatment and can compare the responses. You can show patients exactly how they’re doing through treatment and tell people what they can expect.

Dr. Geer: This came up a lot at our pituitary symposium in April, where we had physicians and patients attend medical talks together. A few people said they had never met another person with their diagnosis, so that was very meaningful for them. We as physicians really need to listen to patients’ symptoms and figure out what we can do to address them. For some of them, a pituitary tumor can be a chronic condition. I tell my Cushing’s and acromegaly patients that I want to know them forever.

Where do you see the clinic in the next five years?

Dr. Tabar: We would like to really engage further with this community of patients and their local physicians. At our symposium, we provided input to other physicians on their challenging cases. We plan to continue to do this and do more tumor boards at MSK regional locations. As a highly specialized center, we tend to see challenging tumors that have failed traditional treatments. Those patients are in great need of additional therapies because they are currently out of options. In collaboration with a dedicated neuro-oncologist, Andrew Lin, we’re putting our collective efforts into developing effective treatments for these patients. We would be very excited if we can move the needle in the right direction for them.