Multiple myeloma is a cancer that arises from the type of white blood cells called plasma cells. When normal plasma cells in the bone marrow develop certain genetic mutations, they may turn into myeloma cells.

At the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH), held December 7 through 10 in Orlando, Florida, Memorial Sloan Kettering researchers reported on some of the latest advances in detecting and treating multiple myeloma.

A New Combination Therapy

One of those studies, led by MSK hematologic oncologist Ola Landgren, Chair of the Myeloma Service, is a phase II clinical trial looking at a new combination of drugs for those recently diagnosed with multiple myeloma.

In this trial, the participants had a targeted antibody drug called daratumumab (Darzalex®) added to a standard chemotherapy combination, called KRD, which is comprised of three drugs: carfilzomib (Kyprolis®), lenalidomide (Revlimid®), and dexamethasone (Ozurdex®).

“After someone completes treatment for multiple myeloma, the measure of how effective that treatment was is called minimal residual disease, or MRD,” Dr. Landgren explains. “MSK uses two very sensitive tests that can detect a single cancer cell in 100,000 or more plasma cells. If we can’t find any cancer, we feel quite confident the treatment has been successful.”

Among the 30 people who got the KRD-daratumumab combination, 77% of them were MRD negative after eight cycles of treatment. Based on cross-study comparison, the average level of MRD negativity seen with other therapies is 54% for those who get KRD alone, 58% for those who get KRD followed by an autologous stem cell transplant, and 59% for those who get a different chemotherapy combination called VRD-daratumumab followed by a transplant.

Daratumumab is currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in people who are unable to have transplants because of age or other health problems. Dr. Landgren says that based on these findings and other emerging studies, he thinks daratumumab could be used more widely.

Along with the biotech company Amgen, Dr. Landgren is working with the FDA to develop a large, randomized, multicenter clinical trial designed to evaluate KRD-daratumumab in comparison to the drug combinations that are currently considered the standard of care. He says that if the new combination is shown to be effective in a head-to-head comparison with current standard treatments, it could lead to wider approval of the drug.

“It’s too early to say that the addition of daratumumab to KRD, as a consequence of the high rate of MRD negativity, will result in an increasing proportion of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients opting for delaying their transplants, but it’s possible that may be the case,” he says. “Transplants are effective, but they are also associated with significant short-term as well as long-term toxicities, whereas side effects from daratumumab are quite minimal. The current phase II study is limited by small numbers and short follow-up, but the early results showing 77% of patients with no MRD are very exciting.”

Learning How Multiple Myeloma Develops

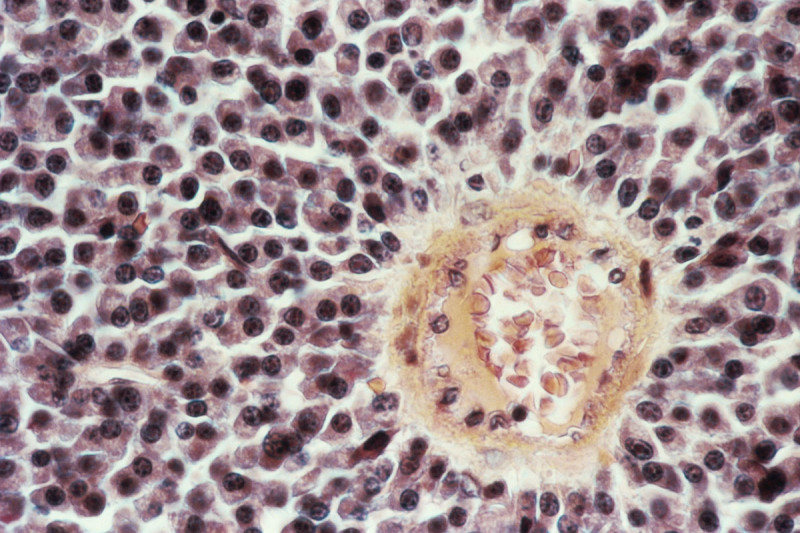

Another important study looked at the early development of multiple myeloma. The disease is diagnosed in about 32,000 people in the United States every year, but experts estimate that by age 60 many more people — from 3% to 5% of the population — will have cells detectable in their blood that show signs of pre-myeloma.

These myeloma precursors can develop years or even decades before symptoms of the disease begin to develop. The symptoms include bone pain and frequent infections. Since the discovery of these early changes was made about ten years ago, the challenge has been determining who is most likely to develop the disease — and therefore should consider closer observation or possibly treatment — and those who don’t need to worry.

In the new research, an international group of investigators led by MSK hematologic oncologist Francesco Maura, a member of Dr. Landgren’s lab, developed a computational algorithm to understand when the first genetic driver of these pre-myeloma cells is acquired. Using genetic information from samples collected through two large, public databases, the researchers were able to reconstruct the life history of these blood cells long before the myeloma developed.

“We were quite surprised to find that many of the key changes associated with myeloma are acquired when people are in their 20s and 30s, even though the average age of disease onset is 63,” Dr. Maura says. “In this study, we developed a way to find the tumor cells’ mutation rate by looking at when the key drivers are accumulated and the degree to which they contribute to the formation of cancer.”

One of the main goals of this research is to understand who has a high risk of ultimately developing cancer so that it can be treated before symptoms start. “We also know that as it progresses, multiple myeloma develops additional mutations that make it more aggressive and harder to treat,” Dr. Maura says. “Ideally, we would want to eradicate the cancer when it is less complex.”