Researchers working to develop better therapies for head and neck cancers have been stymied by problematic side effects. These cancers are sensitive to experimental drugs that block the runaway cell growth resulting from a mutation in a gene called PIK3CA. But these same drugs, called PI3K inhibitors, can cause serious issues — most notably fatigue and a big increase in blood-sugar levels.

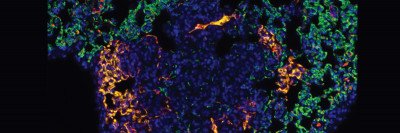

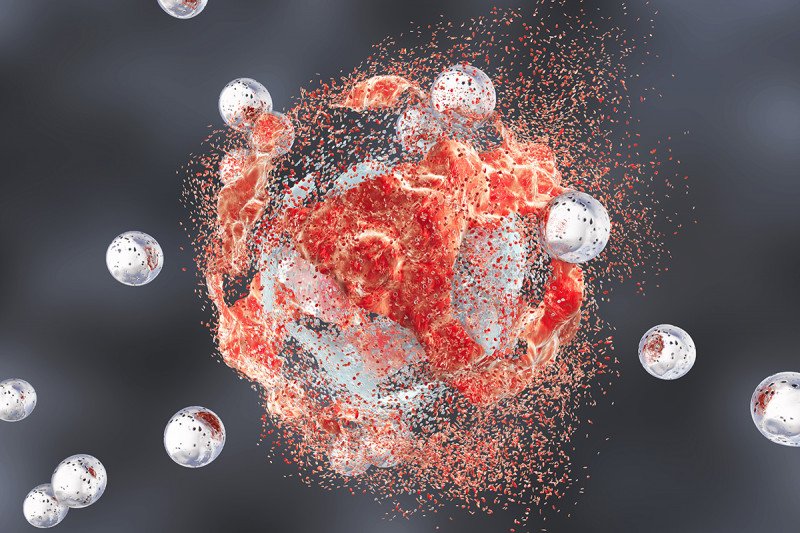

MSK scientists have engineered a novel method for delivering PI3K inhibitors selectively to head and neck tumors using nanotechnology. The technique involves loading the drugs into tiny particles, called nanoparticles, which target a molecule in the blood vessels surrounding tumors. The nanoparticles naturally stick to this molecule, a protein called P-selectin, causing the drug to accumulate at the tumor site.

“We showed in mice that we could achieve the same antitumor effect even using a dose seven times less than what would normally be given systemically,” says cancer biologist Maurizio Scaltriti, who led the study along with molecular pharmacologist Daniel Heller and radiation biologist Adriana Haimovitz-Friedman. “We’re optimistic and excited about getting this into the clinic.”

The method is especially promising for head and neck cancers because P-selectin levels can be elevated by exposure to radiation, the standard treatment for these diseases. This would produce a conspicuous drug target limited to a small area of the body.

A Powerful Technology

Last year, the labs of Dr. Heller and Dr. Scaltriti published a study demonstrating the great potential of targeting P-selectin. Yosi Shamay, a research fellow in Dr. Heller’s lab, made nanoparticles out of an abundant, cheap substance called fucoidan, which is extracted from seaweed and naturally attaches to P-selectin. The P-selectin acts as a kind of molecular Velcro, snagging the nanoparticles so they remain at the tumor site while releasing anticancer drugs.

The new study, published in the journal Nature Communications on February 13 and co-first authored by Dr. Shamay and MSK head and neck surgeon Aviram Mizrachi, models a way to bring this technology to the clinic. (Dr. Mizrachi recently joined the Rabin Medical Center in Israel.) The PI3K pathway is one of the most commonly mutated in human cancers, and PI3K inhibitors are already in clinical trials against a variety of cancers. The specific agent used in this study, called BYL719, is now in phase III trials against breast cancer.

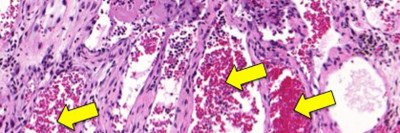

Experiments showed that delivering BYL719 with the nanoparticles effectively blocked cancer cell growth. In the animals, there was no concurrent rise in glucose levels, and the drug showed a sustained antitumor effect.

“When you give a PI3K inhibitor using conventional methods — intravenously or by mouth, so that it goes throughout the body — you see the PI3K pathway being suppressed for a while, but then it goes back up after a few hours as the drug is cleared from the system,” Dr. Scaltriti says. “With nanoparticles, you see this signaling pathway inhibited even after 24 hours, and the blood glucose levels don’t rise. The only explanation is that the drug is accumulating at the tumor.”

A Possible Tipping Point

Dr. Scaltriti says he and his colleagues are evaluating strategies for speeding this approach into human testing. This includes studying how well various drugs can be packed inside fucoidan nanoparticles, which affects how the molecules are released at the tumor site. They also are exploring drug combinations — either by loading two drugs into a single nanoparticle, or having two drugs in separate nanoparticle groups given simultaneously.

“PI3K inhibitors are currently at a delicate stage,” he explains. “Everybody knows they are active against cancer but also that they are difficult to tolerate. This could be one way to shift the balance toward the activity side.”

Dr. Scaltriti is confident that oncologists will want to test this approach in human trials because there currently are few options for treating head and neck cancers after initial therapies fail. He is optimistic it could be tested in humans within the next three years — depending on a number of variables, such as safety approval for fucoidan and collaboration with a drug company.

“In 2017, patients don’t just want to be treated or cured, they also want to have a good quality of life,” he says. “This could be one way to address it, by giving smaller amounts of the drug that all go to the right spot.”