All creatures need to carefully manage their diet to stay alive. Food may not always be available, so organisms from insects to humans have developed an innate sense of when to burn energy and when to save it for later.

Living things stockpile energy in the form of fat cells called adipocytes. If food is plentiful, adipocytes can swell up to store more fat. In leaner times, they release the fat so it can be burned.

When this balance is disrupted, it can cause serious problems. Too much fat storage leads to obesity, but burning too much fat can cause extreme loss of weight and muscle mass. This latter condition, called wasting syndrome or cachexia, is common in people with cancer, making it that much harder to fight the disease.

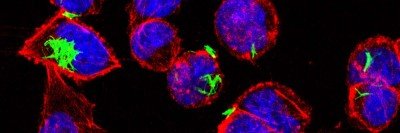

Now, researchers in the Sloan Kettering Institute laboratory of Frederic Geissmann have made an important discovery about this energy regulation process. In mice, they identified a molecular protein called PDGF-CC that signals the adipocytes to take in more fat. The protein is made by immune cells called macrophages.

If the same mechanism holds true in humans, it could be key to developing ways to help people gain or lose weight as needed. Drugs that target PDGF-CC — or its human equivalent — could affect how much fat is stored or burned. This could potentially benefit a large population.

“We’ve identified the protein that is essential for carrying this important signal between macrophages and adipocytes. Without PDGF-CC, energy storage does not occur,” says Nehemiah Cox, a research fellow in the Geissmann lab and the study’s co-first author.

The researchers published their findings on July 2, 2021 in the journal Science.

A ‘Consulting Firm’ for Energy Use

In recent years, researchers suspected that macrophages may be playing an important role in fat storage. Macrophages are found in all tissues and always seem to be closely associated with adipocytes. Were the macrophages telling the adipocytes what to do?

Dr. Cox, along with fellow co-first author Lucile Crozet, also in the Geissmann lab, conducted experiments in fruit flies and mice to get a clearer idea of how macrophages may be influencing adipocytes. They found that when macrophages were completely absent, the adipocytes could not store fat. Mice lacking macrophages stayed lean even when fed a high-fat diet. This seemed to point to macrophages playing a key role in storing fat.

“The macrophages seem to sense the presence of nutrients and make a decision about whether fat should be stored or burned and then direct the adipocytes to do so,” Dr. Geissmann says. “It’s almost like a consulting firm telling a company to either hire more people or save for the future, based on the conditions at the time.”

To identify how this message was sent, the researchers conducted genetic screening of fruit flies. They found that a protein called Pvf3 is essential for fat storage in the fly larvae, which need to conserve energy in order to grow. This finding pointed the researchers to the corresponding protein in mice, PDGF-CC.

Further experiments in mice showed that blocking PDGF-CC prevented fat from being stored, even when macrophages were present. The mice ate and absorbed the normal amount of food, but they quickly burned off the calories.

The next step in the research is to see if the process occurs the same way in people. Dr. Cox is doing experiments using human cells in a dish — including macrophages and adipocytes. The fact that this mechanism has remained through evolution across fruit flies and mice suggests a high likelihood that it will hold true in humans as well.

“Any insight into the process of fat storage or fat burning has implications for a large number of people, not just cancer patients,” Dr. Geissmann says.

- Fat cells act as energy banks, storing or releasing energy as needed.

- Immune cells called macrophages send signals controlling this process.

- In mice, the signal is carried by a protein called PDGF-CC.

- Drugs targeting PDGF-CC could potentially help people control weight gain or loss.