Ellen Horste’s job is a little bit like packing for Mars — where every efficiency and every little bit of room that can be saved matter.

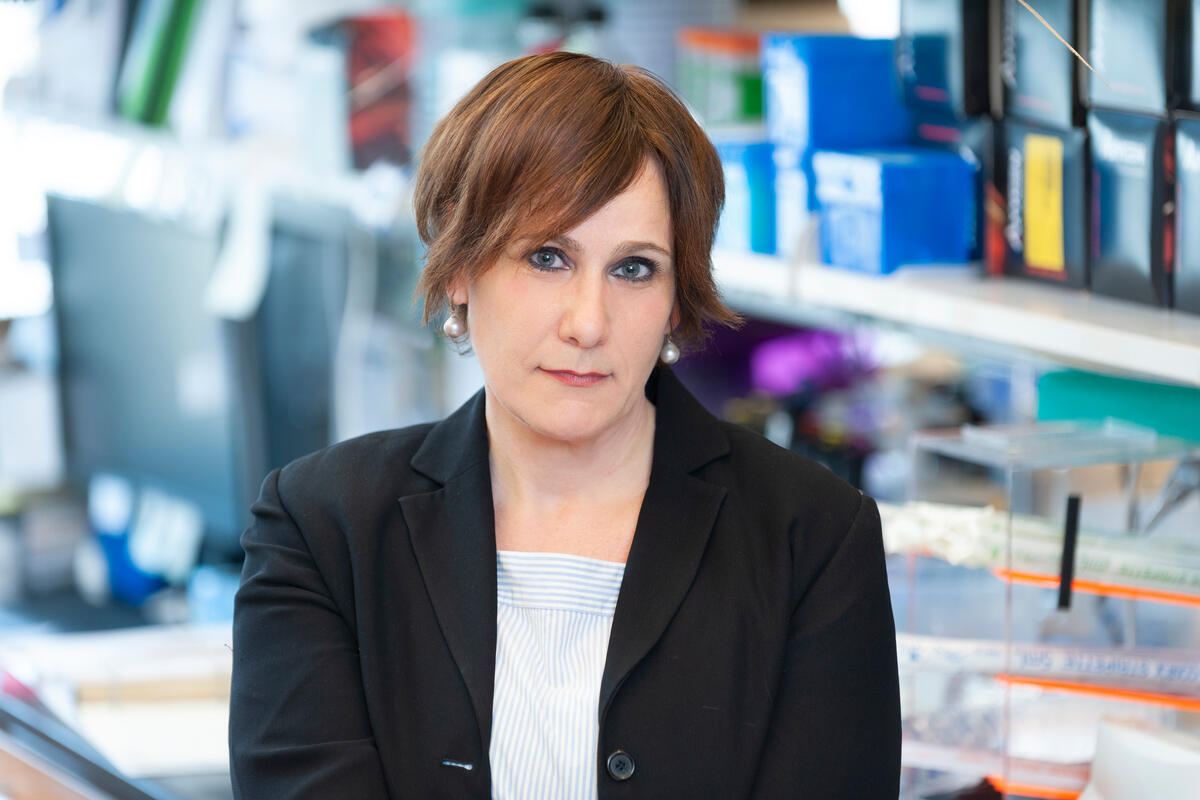

As a payload engineer for a gene therapy startup, Dr. Horste designs genetic elements that get loaded into a virus for delivery into the human body. Once deployed, the treatment’s job is to make therapeutic proteins to replace missing or defective ones.

“The payload space is limited — you only have about 4.7 kilobases of space to work with, and many of the genes that are required to restore function in these diseases are longer than that,” says Dr. Horste, who received her doctorate from the Gerstner Sloan Kettering Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences (GSK) at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) in May. “One of the primary challenges I work on is to take a long protein and figure out what’s the minimum structure we can use.” The length of DNA and RNA is measured by counting pairs of complementary molecules, known as base pairs; a kilobase is equal to 1,000 bases.

Gene therapy is a rapidly evolving field, with more than 30 products already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat hereditary genetic disorders, certain cancers, and other diseases.

And while she’s not at liberty to disclose the specific medical conditions her work aims to address, Dr. Horste says her education and training at MSK did a great job in preparing her for the role.

From Biomedical Engineering to the Lab Bench

Dr. Horste came to the biotech world by a somewhat circuitous route. She studied biomedical engineering as an undergraduate at the University of Michigan, where she discovered that medicine captured her interest a lot more than engineering.

With medical school on her mind, she earned a master’s degree from Loyola University Chicago’s Stritch School of Medicine — but she was ultimately drawn to research and a job as a research technician in the lab of Andrea Schietinger, PhD, at MSK’s Sloan Kettering Institute.

“She was an amazing mentor,” Dr. Horste says. “It was a very collaborative lab — everyone knew what everyone else was working on. Dr. Schietinger would be in the lab doing experiments with us, pipetting with us, and she really encouraged me to take ownership of projects. I didn’t fully realize how special that was at the time.”

Even as medical school acceptances started to roll in, it was Dr. Schietinger who encouraged Dr. Horste to think about a career as a research scientist.

“I had never seriously considered it until then,” she says. “She was very encouraging, and I had such a great experience in her lab, I thought, ‘Yeah, I should do that.’”

Shedding New Light on mRNA Translation

Soon Dr. Horste was enrolled in GSK’s cancer biology doctoral program and working in the lab of another MSK scientist: molecular and cell biologist Christine Mayr, MD, PhD.

From the start, Dr. Mayr challenged her new trainee with an ambitious and technically complex project: isolating and further illuminating the biology of TIS granules, a new, membraneless organelle the lab had discovered.

Dr. Horste’s thesis work showed that different regions throughout the cell are responsible for translating functionally similar types of messenger RNA (mRNA), and the location of translation determines the amount of protein produced by the mRNAs. The findings, which were published in Molecular Cell, could help develop new approaches to increase or alter the production of proteins in mRNA therapies.

“It was very challenging. And for the first two years, I was making very little meaningful progress,” Dr. Horste says. “But one of Dr. Mayr’s great skills is her enthusiasm for science — and it’s infectious. I’d come out of our meetings feeling reinvigorated about the project. She always had faith in me.”

Both of her mentors remember her fondly, as well.

“Ellen is incredibly sharp and picks up new ideas and techniques right away,” Dr. Schietinger says. “That’s why I encouraged her to do a PhD and consider a career in basic science.”

Dr. Mayr, too, recalls Dr. Horste being a quick study: “I was so impressed with her performance during her four-week rotation, I proposed a challenging project for her PhD thesis — isolating TIS granules. Nobody had ever done this, and she just worked her way through it until she succeeded. We were a very good team and were able to work closely together.”

While her experience in each lab was unique, Dr. Horste says both opportunities inspired her and pushed her in new directions.

“Obviously, men can be great scientists and great mentors, but being trained by two powerful, ambitious, intelligent women really helped me to see a future for myself in science,” she says.

A Training Ground Like No Other

Even though Dr. Horste was focused on basic science — on expanding fundamental knowledge about mRNA translation in cells — she says her time at MSK and GSK was an amazing training ground for a career beyond academia.

And she isn’t alone. Two of every 10 graduate students who train in MSK labs take jobs in the pharmaceutical industry or biotech. Another six move on to a postdoctoral fellowship or clinical training. And the remainder pursue other types of jobs or additional degrees.

“At our commencement celebration, I told Dean [Michael] Overholtzer how well the training and education and mentorship I received here had prepared me and how grateful I am for the experience,” Dr. Horste says.

While the technical skills she learned are considered table stakes in biotech and pharma worlds, pursuing a PhD helped her become a better all-around scientist.

“Obviously, you have people to collaborate with and mentors that support you, but at the end of the day, your thesis is your project,” Dr. Horste says. “No one else cares about it the way you do, and it’s only going to move forward if you push it forward. You learn how to get things done.

“That drive and self-determination can be a real asset in an industry environment,” she adds, “not to mention the soft skills I cultivated through participation in clubs like the Tri-I Startup Venture Group and presenting at international conferences such as Gordon Research Conferences.”

‘I Could Go Anywhere and Do Anything’

While MSK is best known as one of the world’s leading cancer research programs, outsiders may not fully appreciate the overall breadth and depth of its scientific research programs, Dr. Horste says.

“Yes, a lot of the research happening at MSK is very translational, but I’m testament to the fact that there’s also exceptional basic science research happening there,” she says. “I got a world-class education in molecular biology — and it put me in a position where I could be open to a variety of career paths working on a variety of diseases. It’s really a platform where I could go anywhere and do anything.”

When she’s not in the lab at Apertura Gene Therapy, you can find Dr. Horste taking in all that New York has to offer — from the city’s cultural and culinary offerings, to networking with other members of the biotech community, to long strolls with her husband, Charlie, and their Goldendoodle, Chester.