Every year, cancer doctors and scientists from around the world converge on Chicago for the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. It is the largest cancer conference in the world. Photo courtesy © ASCO/Scott Morgan 2019

This year’s annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) featured updates on important progress in treating childhood cancers. MSK researchers reported encouraging news about therapies for brain and spine tumors, as well as promising results in treating children with cancer that carries a specific genetic mutation.

Expanding a New Drug to Children

A relatively rare but inviting target for cancer drugs is a mutated form of the protein RET, which is found in many solid tumors. At the 2018 ASCO meeting, a research team announced the results from a phase I study showing that a RET inhibitor called LOXO-292 was safe and effective at slowing tumor growth. The drug appeared to have strong antitumor activity — 77% of people receiving the drug responded.

New research is now suggesting that LOXO-292 may also be safe and effective in children with cancer that has a RET mutation. MSK Kids pediatric oncologists Julia Glade Bender and Michael Ortiz contributed to two posters exhibited at ASCO discussing the promise of the drug. One reported encouraging early results testing LOXO-292 in a small number of children with a variety of solid tumors. The other poster announced the start of a new multicenter phase I clinical trial for children with cancer that has a RET mutation.

Unlike prior RET inhibitors, LOXO-292 is very precise. “LOXO-292 is a lot less toxic to patients, and it seems to work better as well,” Dr. Ortiz says.

Four children with different types of solid tumors containing RET mutations were treated with the drug at different institutions, including one at MSK. The US Food and Drug Administration granted special allowances for each child to receive this treatment on compassionate use. (This involves using an investigational drug to treat a seriously ill patient when no other treatments are available.) LOXO-292 did not cause any serious side effects, and the tumors shrank significantly in all four children.

The girl treated at MSK Kids had a rare cancer that had spread to her lungs and brain. The tumor was identified as having a RET mutation through an initiative called Make an IMPACT. This program offers people with rare cancers genomic testing of their tumor at no cost. A doctor at NYU Winthrop Hospital sent the tumor to MSK Kids for testing. After the RET mutation was found, the girl was transferred to MSK Kids to start on LOXO-292.

“It’s pretty impressive how quickly she’s responded,” says Dr. Ortiz, who discussed the girl’s experience in the presentation “Precision Medicine in Pediatric Solid Tumors” at ASCO.

“I think aside from the drug working, it highlights this new accelerated way of getting drugs to children by using information we’ve gathered from an adult trial,” Dr. Glade Bender says. “We have seen four responses at four institutions showing the treatment is safe. We can be optimistic this upcoming trial will be a success.”

In an Early Trial, Targeted Therapy Shows Promise for Some Children with Cancer

For some children with cancer, conventional therapies, such as chemotherapy, stop working after a time or simply never work at all. Many research efforts have focused on looking for a way to predict which children may not respond and finding them new options.

Targeted therapy may be an option for some of these kids. Results from a phase I/Ib trial of nearly 30 patients being presented at ASCO showed that tumors with particular DNA rearrangements responded to treatment with a targeted therapy called entrectinib.

Entrectinib works by targeting a genetic change called a fusion. This occurs when two unrelated genes join together. Entrectinib targets five gene fusions: NTRK1, 2, and 3, as well as ROS1 and ALK. The 12 people in the study who had fusions in one of those five genes, or another mutation called an ALK mutation, responded to the therapy.

Entrectinib works similarly to larotrectinib (Vitrakvi®, which is also known as LOXO-101). Larotrectinib was approved by the FDA in November 2018 for both children and adults with cancers caused by a genetic mutation called a TRK fusion.

Of the 12 individuals who responded, five had central nervous system (CNS) tumors, six had non-CNS tumors, and one had neuroblastoma. Three patients had a complete response, meaning all signs of cancer disappeared. The remaining nine had a partial response, meaning the tumor got smaller or the extent of the cancer in the entire body was reduced.

“Though it is a small number of patients in this trial, these results are encouraging,” says Ellen Basu, an MSK Kids pediatric oncologist who was an author on the study. “I am looking forward to treating more patients with entrectinib as we continue trials with this targeted agent to learn more about its effectiveness.”

Improving Drug Delivery to a Lethal Brain Tumor

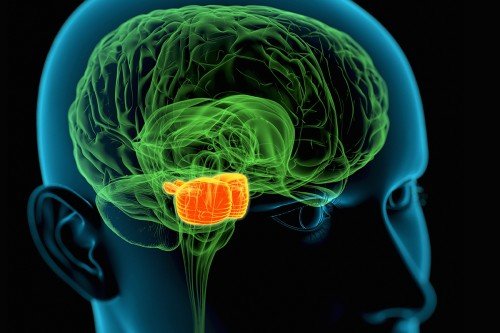

Mark Souweidane, a pediatric neurosurgeon with MSK Kids and Weill Cornell Medicine, presented updated results from a phase I clinical trial testing a new treatment approach for a pediatric brain tumor. Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is one of the deadliest tumors to occur in children. The median survival is less than 12 months. DIPG is difficult to treat because it arises in the brain stem at the base of the brain and is hard to reach with drugs.

Last year, early results from a clinical trial showed that a drug delivery technique called convection enhanced delivery (CED) safely and effectively distributed the drug. The CED approach involves slowly infusing the drug through tubes inserted deep into the brain stem. This extended flow saturates more of the tumor than has been possible through other delivery techniques.

The drug, called omburtamab, is an antibody linked to a radioactive substance. It was developed by MSK Kids physician-scientist Nai-Kong Cheung. The results reported last year showed that 28 children with DIPG who had already received radiation therapy to the tumor were safely given omburtamab using CED.

At ASCO, Dr. Souweidane reported that results are now available from 37 children who were treated with CED. The approach continues to appear safe and enabled some children to live longer — the median survival was 15 months. Nonetheless, the CED technique needs to be further improved to adequately treat DIPG tumors with the drug.

“This treatment strategy has evolved from many years of preclinical research,” he says. “Our treatment of children on this trial has demonstrated clinical benefit, and we are now challenged with identifying what features predict a better outcome. It’s my hope that we will soon embark on a trial aimed at proving a survival advantage, something that has never been shown in DIPG. It is beyond exciting.”