- MACHETE is a new CRISPR-based technique to study large-scale genetic deletions efficiently in laboratory models.

- Using MACHETE, researchers found that a prominent deletion often eliminates a cluster of interferon genes — leading to poorer outcomes in mouse models of pancreatic cancer and melanoma.

- Intact tumor interferons might serve as a biomarker of immunotherapy response.

People are already calling it the Machete Paper.

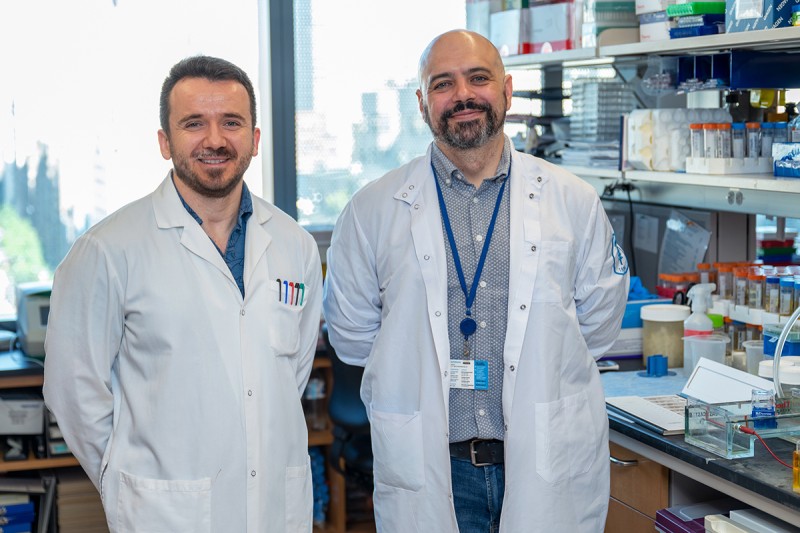

Still, lead authors Francisco “Pancho” Barriga and Kaloyan Tsanov of the Sloan Kettering Institute don’t want the name of their new research technique to overshadow their findings — which shed new light on a genetic change that contributes to about 15% of all cancers, and which might help identify patients likely to respond to immunotherapies.

MACHETE is what the duo call the CRISPR-based method they developed to study copy number alterations, or CNAs, which are large-scale genetic changes that frequently happen in cancer.

The MACHETE acronym stands for Molecular Alteration of Chromosomes with Engineered Tandem Elements. It’s a new way of slicing out significant targeted sections of genetic code to mirror changes that arise in cancer and other human diseases.

This means that, for the first time, there’s a straightforward and efficient way to study CNA deletions in laboratory models — such as the mouse models of pancreatic cancer and melanoma used in their study, which was published in Nature Cancer on November 7, 2022.

“In the beginning, we didn’t even want to put MACHETE in the title of our paper, to better highlight the fascinating biology we found,” says Dr. Barriga, a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute, which is the experimental research arm of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK).

Still, that didn’t stop a labmate from taping a photo of the famous Danny Trejo character, Machete, to his desk after he presented the work for the first time. Nor another scientist from tweeting a copy of the paper’s preprint at the actor’s Twitter handle. (The gesture went unrequited, alas.)

Beyond Single-Gene Cancer Mutations

To understand the ways in which the study broke new ground regarding one of the most common copy number alterations in human cancers — and what it might mean for patients in the future — one needs to appreciate the underlying biology.

Many people think of mutations in cancer as small “typos” in the genetic code that affect the activity of a single gene — either turning it on or shutting it off. And for decades, researchers, too, have primarily focused on these tiny errors that drive many types of cancer.

Copy number alterations, however, can affect dozens of genes simultaneously, and duplicate or delete large sections of individual chromosomes.

A typical tumor carries an average of 24 different CNAs that impact up to 30% of its genome, the researchers note.

“Point mutations are relatively easier to study than CNAs,” says Dr. Tsanov, who, like Dr. Barriga, is a postdoc in the lab of investigator Scott Lowe, the study’s senior author and Chair of the Institute’s Cancer Biology & Genetics Program. “But CNAs are just as important — they’re just a lot more complex.”

Tumors with a higher level of CNAs — also known as CNA burden — are linked to recurrence and worse outcomes in breast, prostate, endometrial, renal clear cell, thyroid, and colorectal cancer, previous MSK research found.

But, again, the size and variety of the changes — affecting thousands, or even millions, of base pairs of DNA rather than just the alteration of a single letter in the DNA sequence — has made them very difficult to re-create in laboratory models for close study.

A potential new approach to studying large-scale deletions came to Dr. Barriga while heading home from the lab on the Roosevelt Island tram.

“I wondered: ‘How can we select cells with the intended deletions even if they are very rare?’ ” he says. “I got an idea and drew up the initial concept for what would be the general strategy that evening. When we tried it, it just worked. I may never have something come together that smoothly for the rest of my career.”

Coming up with the right combination of words to make the MACHETE acronym work took longer, he jokes.

But the duo knew they were onto something when genetic changes made with MACHETE in a mouse model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma resulted in the same outcomes as a similar naturally occurring mutation in a different mouse model that Dr. Tsanov was studying for a separate project.

“It was really a close collaboration from there on in,” Dr. Tsanov says. The research team also included more than a dozen other scientists from MSK, the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, and the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto.

Research May Help Identify Which Patients Will Benefit From Immunotherapy

After the genetically “macheted” cells were inserted into the pancreases of laboratory mice, the mice developed cancer. The genetic alterations removed a slice of chromosome 9, and with it a gene known as CDKN2A — a well-established tumor-suppressor gene. As expected, this shut down the cells’ innate ability to prevent the emergence of tumor cells.

This broad slice also removed the genetic code for a cluster of interferons — proteins that trigger immune cells to fight off invaders, like cancer cells — whose importance the scientists wanted to test.

One of the most prevalent CNAs in people affects this chromosomal region — 9p21.3 — and about half of patients with it develop tumors in which these interferons are also missing.

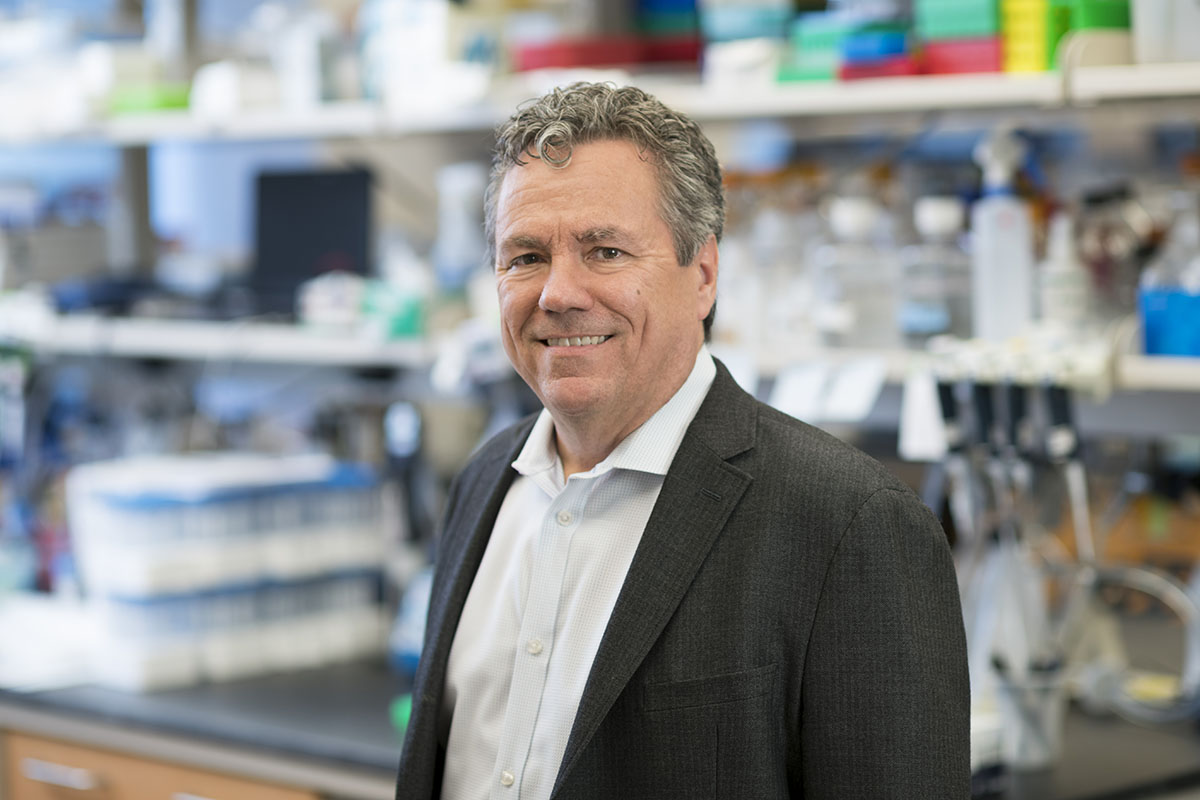

“We have known about CDKN2A mutations for a long time, and it was already remarkable how they worked,” says Dr. Lowe, who is also a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator. “This study says there is so much more to it, with important therapeutic implications.”

The additional loss of the interferons creates a one-two punch that makes the tumors invisible to defenders in the immune system and helps the cancer to spread, the researchers discovered.

“It’s been hard to study these interferons because they’re encoded by a cluster of 16 genes,” Dr. Lowe adds. “Using MACHETE revealed a major way in which developing cancer cells avoid being recognized by the immune system, and which can also lead to resistance to immunotherapies aimed at reactivating the immune system to attack the cancer.”

Co-author Dana Pe’er, a computational biologist at the Sloan Kettering Institute, was instrumental in helping the team understand how the disruption of interferon genes affected immune cells and helped the cancer to evade the immune system, Dr. Lowe says.

In addition to pancreatic cancer, the findings held true for a mouse model of melanoma.

The research suggests, then, that patients whose interferon region is still intact may be better candidates for immunotherapy than those who have lost it. Immunotherapies can work wonders, but one of the great challenges has been in identifying which patients’ cancers will respond to them and which won’t.

Even cutting-edge genomic tests, like MSK-IMPACT®, however, don’t typically collect information about this cluster of interferon genes. Further study could show whether adding it to sequencing tests could help identify patients who are more likely to benefit from immunotherapy, Dr. Lowe notes.

Meanwhile, CNA deletions have been linked to a variety of human genetic disorders called chromosomal deletion syndromes.“So, MACHETE provides a new framework for investigating large deletion events beyond just cancer,” Dr. Barriga says, noting a half a dozen other research groups are already using the Sloan Kettering Institute–developed technique.