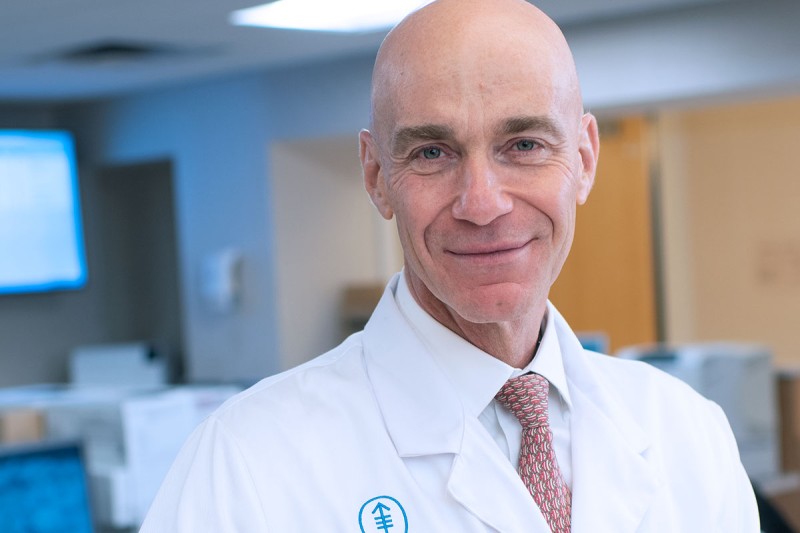

Memorial Sloan Kettering breast cancer expert Mark Robson.

These days, anyone with an interest and about $100 can spit into a tube, mail it to a genetic testing company, and get back details on their DNA. This is known to some as recreational genomics. But the results of such tests can be anything but amusing when they include genes that influence cancer risk.

Two widely tested cancer-predisposition genes are BRCA1 and BRCA2. Certain inherited mutations in these genes are known to greatly increase the risk of developing several types of cancer, including breast, ovarian, prostate, and pancreatic cancers. Genetic testing for BRCA mutations can identify people who may benefit from risk-reduction surgery, like a mastectomy; preventive medications; or targeted therapies.

But there is a huge catch: Commercial testing kits, like the one from 23andMe authorized by the US Food and Drug Administration, test for only the three most common BRCA mutations known to run in families of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry. Someone could test negative for these specific mutations and still be at risk for cancer from other BRCA mutations that aren’t included in the test. This false sense of security might dissuade someone from finding out the full extent of their cancer risk.

This is just one of the many reasons why doctors typically recommend that genetic testing be done under the guidance of a clinical genetics expert who can test for more than the most common BRCA mutations and help explain the results. Even then, questions remain about who should have testing.

What the Experts Say

Currently, doctors refer someone for genetic testing if they meet various clinical criteria, like having a family history of cancer or being diagnosed with certain cancers at a young age. But there is evidence that by limiting testing to just these individuals, some people with a BRCA mutation will be missed.

“We know from our data at Memorial Sloan Kettering that if you only test people with strong family histories, you miss half the cases,” says Larry Norton, Senior Vice President in the Office of the President and Medical Director of the Evelyn H. Lauder Breast Center at MSK.

Between those with a family history and the entire US population is a large unmapped territory. Just 0.3% of the population (one in 300 individuals) has a dangerous BRCA mutation. It’s not clear how to step up testing in a logical and efficient manner to capture those who are at risk.

But testing guidelines are indeed becoming more inclusive. In August, the US Preventive Services Task Force, an independent panel of health experts, issued updated BRCA testing recommendations. In addition to women with a known family history of breast or ovarian cancer, the updated recommendations include two additional groups: women who previously had breast or ovarian cancer and are now considered cancer free and women of an ancestry known to be at a higher risk, such as Ashkenazi Jewish women. One in 40 individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry (2.5%) have a harmful BRCA mutation. The updated recommendations were published August 20 in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

In an accompanying editorial, Mark Robson, Chief of the Breast Medicine Service at MSK, and Susan Domcheck from the University of Pennsylvania, call the addition of women with prior breast and ovarian cancer “an important step forward” and applaud the decision to include ancestry as a reason for testing.

“Identification of individuals at risk of carrying a BRCA1/2 mutation can be lifesaving and should be a part of routine medical care,” they write.

Low Uptake, Risks of Overtesting

Even as testing guidelines are becoming broader, there is evidence that people who are good candidates for testing are not currently availing themselves of it. For example, approximately 15% of women with epithelial ovarian cancer have a BRCA1/2 mutation. Given this high frequency, experts recommend testing for all people with ovarian cancer. But that doesn’t happen: Less than 30% of such women are actually tested. The numbers are even lower for underrepresented minorities and those from a low socioeconomic background.

On the flip side, Dr. Robson and his co-author caution that there are dangers to overtesting, especially when the tests in question are large multigene panels that can include up to 80 genes.

“While there may be value in expanding BRCA testing, particularly in the Ashkenazi Jewish population, this does not automatically mean that this expansion should be conducted using multigene panel tests,” they write.

MSK scientists, including a team led by Kenneth Offit, Chief of the Clinical Genetics Service, are actively exploring the best and most strategically effective ways of testing. They are committed to making sure that the most beneficial testing is offered to the people who need it.