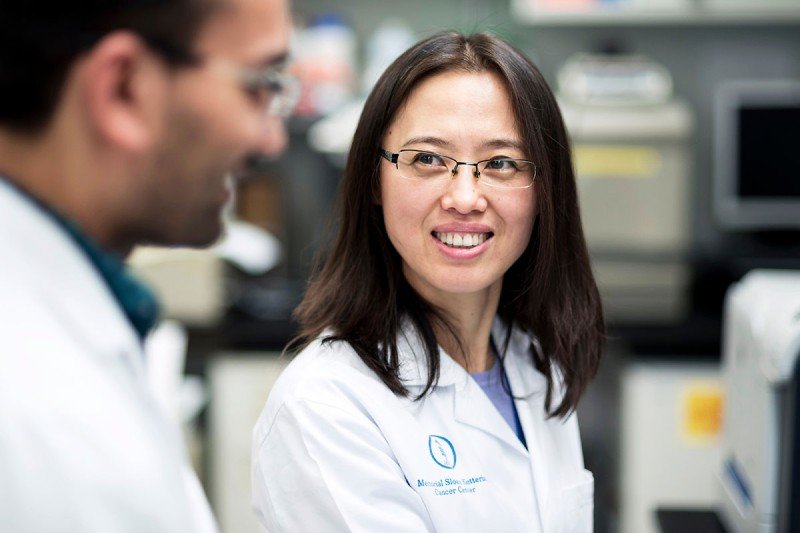

"We treat every patient’s cells with the utmost care,” says Xiuyan Wang, Assistant Director of the Cell Therapy and Cell Engineering Facility at Memorial Sloan Kettering.

Against one wall of Xiuyan Wang’s office is a floor-to-ceiling bookcase stuffed with thick colored binders. Each one represents a patient treated at MSK with an immunotherapy called CAR T cells.

The binders are color coded: orange for chronic lymphocytic leukemia, black for Hodgkin lymphoma, blue for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), red for ovarian cancer. There are about 300 binders in all.

“You see the shelf is kind of bulging already,” Dr. Wang says.

As Assistant Director of the Cell Therapy and Cell Engineering Facility at MSK, Dr. Wang is responsible for manufacturing CAR T cells, a type of “living drug,” for infusion into patients.

Each colored binder represents a patient treated with CAR T cell therapy at MSK.

CAR stands for chimeric antigen receptor. It’s a designer protein that scientists genetically engineer into a person’s own immune cells. This addition turns them into souped-up cancer fighters.

Dr. Wang is part of a large orchestra of players who collaborate to bring these living therapies to life. But you might say she’s the maestro, since she’s the one making the powerful cells.

“I remember one of the patients very vividly,” Dr. Wang says. “He was an ALL patient. The primary investigator from the clinical trial came to us and said, ‘The family wants to meet the people who are making the magic cells.’ So we met with them. The son was very happy to see us. He said it helped his father to feel like we would treat his cells with the utmost care.”

“We actually treat every patient’s cells with the utmost care,” she adds.

Making the First CAR T Cells

Care in this context means following a strict protocol called a standard operating procedure. Or rather, procedures — since it takes about 250 of them to produce one batch of CAR T cells.

The person most responsible for devising those critical instructions is Isabelle Rivière, Director of MSK’s Cell Therapy and Cell Engineering Facility. An immunologist trained in France and the United States, Dr. Rivière began contemplating cell therapies as a graduate student in the 1990s. She was inspired by work being done on HIV at the time. An adviser of hers was interested in using genetic engineering to prevent T cells from being infected by HIV. “This was a very avant-garde idea at the time,” she says.

Dr. Rivière completed her graduate studies at the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she met fellow CAR T pioneer (and future husband) Michel Sadelain, with whom she now collaborates at MSK.

Following a postdoctoral fellowship at New York University, Dr. Rivière was recruited to MSK in 1998 to set up a clinical-grade gene transfer facility, one of the first in the country. “I was appointed co-director and given the keys to the facility,” she says.

She spent more than a decade patiently working out the complicated recipe that coaxes healthy CAR T cells into existence.

“I can honestly say I don’t think we knew what we were getting into,” she says. “We were really establishing the field as we went.”

The manufacturing process that she and her team developed involves capturing T cells with magnetized beads and delivering the CAR gene to the cells with a modified virus. They are then grown in baglike incubators rolling on an oscillating tray. The gentle rocking motion keeps the cells happy and well-fed as they grow.

Today, the cell manufacturing facility takes up two entire floors of the Zuckerman Research Center on MSK’s campus. It resembles the interior of a futuristic spaceship, with sparkling clean glass-walled rooms. A team of 30 technicians keeps the facility humming.

That’s a far cry from where things began in 1998. Initially, Dr. Rivière had one technician to help her, shared with another investigator. “That’s an increase of about a technician and a half per year,” she quips.

Isabelle Rivière (left) directs the Cell Therapy and Cell Engineering Facility at MSK.

CAR T Cells for Leukemia

The MSK team chose to engineer T cells to target a molecule found on blood cells called CD19. They showed that this approach worked in mice back in 2003. But it wasn’t until they tried the therapy in people with B cell ALL that they knew they were onto something special.

“The most dramatic result was when we took the bone marrow of these patients a couple of weeks postinfusion, and the disease had completely vanished,” Dr. Rivière says. “That was really the eureka moment. We had to convince ourselves that this was real.”

Clinical trials of the CAR T cells in people with ALL began in 2010. As of 2018, 53 adults with refractory ALL have been treated at MSK, and the majority of them have benefited, with some still alive after more than five years. The team published those results in 2018 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Many people who were facing a grim prognosis are now alive and well, thanks to CAR T cell therapy. “That’s very important, and often the impact of the quality of the manufacturing process is underestimated,” Dr. Rivière says.

What’s Next? Solid Tumors

The US Food and Drug Administration approved the first two CAR T cell therapies in 2017. One is for children and young adults with ALL and adults with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Another is for adults with NHL. More approvals are likely to come.

Researchers at MSK and elsewhere are developing new CARs that can target other types of cancers, with an eye toward solving the most challenging problems.

“We want to extend this approach to solid tumors,” Dr. Rivière says. “That’s the next frontier.”