Gynecologic cancers are difficult to treat if diagnosed at a late stage. Immunotherapy holds great potential for improving the outlook of women with these diseases.

Gynecologic cancers are challenging to treat. They can be hard to find and are usually diagnosed when they are advanced. Although these cancers can be held at bay with surgery or chemotherapy, they often return and become difficult to control. Researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering are exploring whether harnessing the power of the immune system could better combat these stubborn diseases.

There are logical reasons to think that gynecologic cancers may respond to immunotherapy. Some of these cancers carry genetic mutations that are known to respond to these drugs. Others bear clinical markers showing that the immune system is already primed to respond. Ovarian cancers, for example, are typically infiltrated by immune cells. This means the immune cells were drawn to these tumors, even if they ultimately were not effective. Most cases of cervical cancer are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), which the immune system normally fights off.

“We know there’s some loss of immune control that allows gynecologic cancers to develop or recur,” says MSK medical oncologist Claire Friedman. “So it makes sense to take an immunotherapy approach for these diseases.”

Endometrial Cancer: Boosting Checkpoint Inhibitors

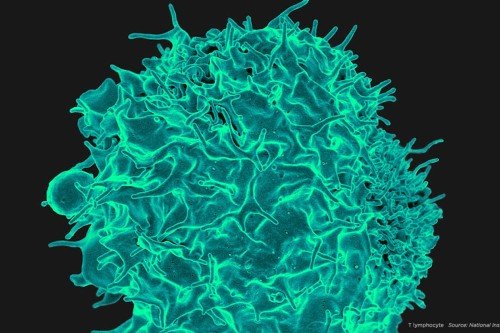

One type of immunotherapy showing great promise is a class of drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors. These drugs work by releasing a natural brake on T cells so they can recognize and attack tumors.

A major development in the last year was the FDA approval of the checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab for cancers that have a genetic abnormality called mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency. This genetic flaw prevents cells from fixing mistakes that occur when DNA copies itself. As a result, MMR-deficient cells can have hundreds or even thousands of mutations, compared with just a few dozen in a typical cancer cell. This pattern of widespread genetic change is called microsatellite instability.

The effectiveness of checkpoint blockade drugs against MMR-deficient tumors bodes especially well for the treatment of endometrial cancer, since about 30% of endometrial tumors are MMR-deficient.

“The approval of pembrolizumab for the MMR subtype of endometrial cancer was the proof of principle that this type of immunotherapy can be successful in a gynecologic cancer,” Dr. Friedman says. She is now leading a phase II clinical trial testing another checkpoint inhibitor, nivolumab (Opdivo®), in people with endometrial tumors that are either MMR-deficient or otherwise have a high number of genetic mutations.

So far, checkpoint inhibitors have been effective in a relatively small number of patients with gynecologic cancers.

In order to increase the number of people who benefit, Dr. Friedman is hoping to clarify what makes gynecologic tumors either vulnerable or resistant to immunotherapy. This can include the genetic makeup of the tumor itself, as well as the type and activity of the cells surrounding it — what is known as the tumor microenvironment.

For example, research at MSK and elsewhere suggests that checkpoint inhibitors can be more effective if they are given along with drugs that alter the blood vessels surrounding and nourishing the tumors.

Medical oncologist Vicky Makker is leading a phase Ib/II study testing pembrolizumab in combination with a drug called lenvatinib (Lenvima®) in women with advanced endometrial cancer — regardless of whether the tumors have microsatellite instability. Lenvatinib blocks several enzymes, including those involved in the formation of tumor blood vessels. It is already FDA approved for the treatment of a type of thyroid cancer. Early results presented in June 2017 at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology were promising.

Ovarian Cancer: Multiple Treatment Strategies

Researchers are exploring a similar combination approach to treat ovarian cancer. MSK medical oncologist Roisin O’Cearbhaill is leading a large phase III trial testing the checkpoint blockade drug atezolizumab (Tecentriq®) combined with chemotherapy and another drug, bevacizumab (Avastin®), which interferes with blood vessel growth. The therapy is being tested in women with advanced ovarian cancer that has continued to grow despite treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy.

There are other strategies for enhancing the immune system’s ability to recognize cancer cells as foreign. One investigative treatment combines checkpoint inhibitor drugs with cancer vaccines. The idea behind cancer vaccines is that they make it easier for the immune system to detect the tumor by telling it what the foreign substance looks like.

Therapeutic Cancer Vaccines: How They Work

“It would be wonderful if we could teach the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells,” Dr. O’Cearbhaill says. “But it’s not as simple as that. Cancer cells are continually changing and they have a lot of tools enabling them to hide out in the body.”

Dr. O’Cearbhaill is currently leading a phase I trial combining nivolumab with a vaccine called WT1, which was developed by physician-scientist David Scheinberg, Director of MSK’s Center for Experimental Therapeutics.

Another phase I trial led by Dr. O’Cearbhaill is exploring the use of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy, in which a patient’s own T cells are engineered to attack cancer. The CAR T cells are modified to target a protein called MUC16ecto on the surface of ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal tumors that have come back after prior therapy. The first CAR T therapy was approved by the FDA for the treatment of leukemia and lymphoma earlier this year. The technology shows great promise for many cancers.

Cervical Cancer: Building on HPV Vaccine Success

The development of a vaccine for HPV more than ten years ago was a major advance for preventing cervical cancer. For those who have cervical cancer, checkpoint blockade could be effective. Pembrolizumab has already been approved by the FDA for the treatment of certain head and neck cancers caused by HPV, and it is showing promise in clinical trials against cervical cancer.

Other checkpoint inhibitor combinations are being explored at MSK for cervical cancer. Dr. Friedman is leading a phase II trial testing a combination of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in women with cervical cancer that has spread, come back, or continued to grow despite previous treatment. A phase I trial, led by medical oncologist Matthew Hellman, is testing two checkpoint inhibitors — durvalumab (Imfinzi®) and IPH2201 — in a variety of solid tumors, including cervical cancer.

Though immunotherapy for gynecologic cancers is currently lagging behind immune-based treatments for melanoma and lung cancer, Dr. Friedman is convinced this therapeutic approach will play a big role.

“We’ve seen lasting responses with different combinations,” she says. “While a particular therapy may not be effective for everyone, there usually is a subset that will benefit greatly — and we’re learning to figure out who they are.”